![]()

Just as the themes of the original feast of the Epiphany (also called "Theophany") are now spread over two feast days in the Latin West so that the theological richness of the Epiphany can have full liturgical expression, so the themes of the feast of Pentecost are celebrated on two Sundays instead of one. The feast of the Baptism of Christ follows the Epiphany which puts all its emphasis on the visit of the Magi, and Trinity Sunday follows Pentecost which puts all its emphasis on the descent of the Holy Spirit to such an extent that it is easy to forget that the main effect on the Church of this descent is it's being taken up into the life of the Trinitarian God. Unfortunately, those who reformed the liturgy made the mistake of abolishing the Octave of Pentecost which gives to Trinity Sunday its underlying meaning.

To show how the doctrine of the Trinity is implicit in Pentecost, here is an exerpt from the sermon of Dom Paul, the Abbot of Belmont, which he preached at Pentecost and which we published at that time: In the four Gospels, it is Jesus, the incarnate Son of God, who takes centre stage as, moved by the Spirit, he makes known the Father’s love and reveals the face of God to us, while in the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles of St Paul, it is the Holy Spirit who inspires every thought, word and deed of the early Church and enables the first Christians to understand and acknowledge the revelation of Jesus Christ, in whose Name alone can we be saved and reconciled with God. Early Church fathers, such as St Irenaeus, spoke of the Son and the Spirit as being the right and left hands of God. Trinitarian theology is always heady stuff, so let’s steer clear of that this morning. Suffice it to say that today, the Feast of Pentecost, we focus in a special way on the Person and work of the Holy Spirit, while recognising that the Holy Trinity, being three Persons in one God, is truly one undivided and indivisible God, whose threefold Being has been shared with us, his creatures, created, as we are, in his image and likeness.

One thing that always strikes us about the coming of the Holy Spirit in the New Testament is the joy and excitement his presence brings to individuals, families and communities, indeed to the whole Church. Then there is the element of surprise. Who more surprised, even shocked, than Our Lady when the Archangel Gabriel informed her of the Holy Spirit’s work and her role in the Mystery of the Incarnation? Where the Spirit is, there is Jesus. Think of the Sacraments: it is the Spirit who sanctifies the water, but Jesus who baptises; it is the Spirit who is received, but Jesus who confirms; it is the Spirit who consecrates, but Jesus who is present in the Blessed Sacrament; it is through the power of the Spirit that Jesus absolves us of our sins; it is the Spirit who brings a man and a woman together, yet Christ who blesses their union, the Spirit making it fruitful; it is the Spirit who is consecrates a priest to become alter Christus, another Christ; it is the Spirit who anoints, yet Christ who heals. You can see where the idea of the right and left hands of God came from. and we live entirely in his embrace. There is no aspect of our lives that God does not touch and make holy through the coming and indwelling of the Spirit. In fact, it is the Holy Spirit who gives us the mind and heart of Christ and so makes us pleasing to the Father. It is the Spirit who enables us to pray and to cry out. “Abba, Father.” Today, not only do we give thanks for the gift of the Spirit, the joy of Whitsun, but we also ask to become more conscious of his presence within us, that we might live each day guided only by the Holy Spirit....

Feast of the Most Holy Trinity

(by Fr. Prosper Gueranger 1870)

The very essence of the Christian Faith consists in the knowledge and adoration of One God in Three Persons. This is the Mystery whence all others flow. Our Faith centers in this as in the master-truth of all it knows in this life, and as the infinite object whose vision is to form our eternal happiness; and yet, we only know it, because it has pleased God to reveal Himself thus to our lowly intelligence, which, after all, can never fathom the infinite perfections of that God, who necessarily inhabiteth light inaccessible (1 Tim. vi. 16). Human reason may, of itself, come to the knowledge of the existence of God as Creator of all beings; it may, by its own innate power, form to itself an idea of His perfections by the study of His works; but the knowledge of God's intimate being can only come to us by means of His own gracious revelation.

It was God's good-pleasure to make known to us His essence, in order to bring us into closer union with Himself, and to prepare us, in some way, for that face-to-face vision of Himself which He intends giving us in eternity: but His revelation is gradual; He takes mankind from brightness unto brightness, fitting it for the full knowledge and adoration of Unity in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity. During the period preceding the Incarnation of the eternal Word, God seems intent on inculcating the idea of His Unity, for polytheism was the infectious error of mankind; and every notion of there being a spiritual and sole cause of all things would have been effaced on earth, had not the infinite goodness of that God watched over its preservation.

Not that the Old Testament Books were altogether silent on the Three Divine Persons, Whose ineffable relations are eternal; only, the mysterious passages, which spoke of them, were not understood by the people at large; whereas, in the Christian Church, a child of seven will answer them that ask him, that, in God, the three Divine Persons have but one and the same nature, but one and the same Divinity. "When the Book of Genesis tells us, that God spoke in the plural, and said: Let Us make man to our image and likeness (Gen. i. 26), the Jew bows down and believes, but he understands not the sacred text; the Christian, on the contrary, who has been enlightened by the complete revelation of God, sees, under this expression, the Three Persons acting together in the formation of Man; the light of Faith develops the great truth to him, and tells him that, within himself, there is a likeness to the blessed Three in One. Power, Understanding, and Will, are three faculties within him, and yet he himself is but one being.

In the Books of Proverbs, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus, Solomon speaks, in sublime language, of Him Who is eternal Wisdom; he tells us, and he uses every variety of grandest expression to tell us, of the divine essence of this Wisdom, and of His being a distinct Person in the Godhead; but, how few among the people of Israel could see through the veil? Isaias heard the voice of the Seraphim, as they stood around God's throne; he heard them singing, in alternate choirs, and with a joy intense because eternal, this hymn: Holy! Holy! Holy! is the Lord (Is. vi. 3)! but who will explain to men this triple Sanctus, of which the echo is heard here below, when we mortals give praise to our Creator? So, again, in the Psalms, and the prophetic Books, a flash of light will break suddenly upon us; a brightness of some mysterious Three will dazzle us; but, it passes away, and obscurity returns seemingly all the more palpable; we have but the sentiment of the divine Unity deeply impressed on our inmost soul, and we adore the Incomprehensible, the Sovereign Being.

The world had to wait for the fullness of time to be completed; and then, God would send, into this world, His Only Son, Begotten of Him from all eternity. This His most merciful purpose has been carried out, and the Word made Flesh hath dwelt among us (St. John, i. 14). By seeing His glory, the glory of the Only Begotten Son of the Father (Ibid), we have come to know that, in God, there is Father and Son. The Son's Mission to our earth, by the very revelation it gave us of Himself, taught us that God is, eternally, Father, for whatsoever is in God is eternal. But for this merciful revelation, which is an anticipation of the light awaiting us in the next life, our knowledge of God would have been too imperfect. It was fitting that there should be some proportion between the light of Faith, and that of the Vision reserved for the future; it was not enough for man to know that God is One.

So that, we now know the Father, from Whom comes, as the Apostle tells us, all paternity, even on earth (Eph. iii. 15). We know Him not only as the creative power, which has produced every being outside Himself; but, guided as it is by Faith, our soul's eye respectfully penetrates into the very essence of the Godhead, and there beholds the Father begetting a Son like unto Himself. But, in order to teach us the Mystery, that Son came down upon our earth. Himself has told us expressly, that no one knoweth the Father, but the Son, and he to whom it shall please the Son to reveal Him (St. Matth. xi. 27). Glory, then, be to the Son, Who has vouchsafed to show us the Father! and glory to the Father, Whom the Son hath revealed unto us!

The intimate knowledge of God, has come to us by the Son, Whom the Father, in His love, has given to us (St. John, iii. 16). And this Son of God, Who, in order to raise up our minds even to His own Divine Nature, has clad Himself, by His Incarnation, with our Human Nature, has taught us that He and His Father are one (St. John, xvii. 22); that they are one and the same Essence, in distinction of Persons. One begets, the Other is begotten; the One is named Power; the Other, Wisdom, or Intelligence. The Power cannot be without the Intelligence, nor the Intelligence without the Power, in the sovereignly perfect Being: but, both the One and the Other produce a Third term.

The Son, Who had been sent by the Father, had ascended into heaven, with the Human Nature which He had united to Himself for all future eternity; and, lo! the Father and the Son send into this world the Spirit Who proceeds from them both. It was a new Gift, and it taught man that the Lord God was in Three Persons. The Spirit, the eternal link of the first Two, is Will, He is Love, in the divine Essence. In God, then, is the fullness of Being, without beginning, without succession, without increase, for there is nothing which He has not. In these Three eternal terms of His uncreated Substance, is the Act, pure and infinite.

The sacred Liturgy, whose object is the glorification of God and the commemoration of His works, follows, each year, the sublime phases of these manifestations, whereby the Sovereign Lord has made known His whole self to mortals. Under the somber colors of Advent, we commemorated the period of expectation, during which the radiant Trinity sent forth but few of its rays to mankind. The world, during those four thousand years, was praying heaven for a Liberator, a Messiah; and it was God's own Son that was to be this Liberator, this Messiah. That we might have the full knowledge of the prophecies which foretold Him, it was necessary that He himself should actually come: a Child was born unto us (Is. ix. 6), and then we had the key to the Scriptures. When we adored that Son, we adored also the Father, Who sent Him to us in the Flesh, and to whom He is consubstantial. This Word of Life, Whom we have seen, Whom we have heard, Whom our hands have handled (St. John, i. l) in the Humanity which He deigned to assume, has proved Himself to be truly a Person, a Person distinct from the Father, for One sends, and the Other is sent. In this second Divine Person, we have found our Mediator, Who has reunited the creation to its Creator; we have found the Redeemer of our sins, the Light of our souls, the Spouse we had so long desired.

Having passed through the mysteries which He Himself wrought, we next celebrated the descent of the Holy Spirit, Who had been announced as coming to perfect the work of the Son of God. We adored Him, and acknowledged Him to be distinct from the Father and the Son, Who had sent Him to us, with the mission of abiding with us (St. John, xiv. 16). He manifested Himself by divine operations which are especially His own, and were the object of His coming. He is the soul of the Church; He keeps her in the truth taught her by the Son. He is the source, the principle of the sanctification of our souls; and in them He wishes to make His dwelling. In a word the mystery of the Trinity has become to us, not only a dogma made known to our mind by Revelation, but, moreover, a practical truth given to us by the unheard of munificence of the Three Divine Persons; the Father, Who has adopted us; the Son Whose brethren and joint-heirs we are; and the Holy Ghost, Who governs us, and dwells within us.

Let us, then, begin this Day, by giving glory to the one God in Three Persons. For this end, we will unite with holy Church, who, in her Office of Prime, recites on this solemnity, as, also, on every Sunday not taken up by a feast, the magnificent Symbol, known as the Athanasian Creed. It gives us, in a summary of much majesty and precision, the doctrine of the holy Doctor, Saint Athanasius, regarding the mysteries of the Trinity and Incarnation (It is a psalm or hymn of praise, of confession, and of profound, self-prostrating homage, parallel to the Canticles of the elect in heaven. It appeals to the imagination quite as much as to the intellect. It is the war-song of faith, with which we warn first ourselves, then each other, and then all those who are within its hearing, and the hearing of the Truth, Who our God is, and how we must worship Him, and how vast our responsibility will be if we know what to believe, and yet believe not.)

LITURGY AND TRINITY

Towards an Anthropology of the Liturgy

by Stratford Caldecott

By the early twentieth century, the battle-lines were drawn up between Rationalists and Romantics, Modernists and defenders of the ancien régime. Outside these categories, but at the time (and to some extent even today) insufficiently distinguished from them, the work of ressourcement was being carried forward by such figures as Maurice Blondel, Odo Casel, Romano Guardini, Louis Bouyer and Henri de Lubac. These men were trying to escape the nineteenth-century impasse by looking further back than the Baroque, further than the Middle Ages, back to the undivided Church of patristic times. In the writings of the Church Fathers they believed they had found a way beyond the opposition of subjectivism and objectivism. The mystery of "participation" would provide the key to a genuine renewal, not merely of the letter but of the spirit of the Catholic liturgy.

According to Blondel and de Lubac, a distortion had crept into Catholic sensibility with the Enlightenment. The distortion amounted to a tendency to separate grace from nature. The Rationalist mentality demanded a world in which natural reason could operate without interference from the theologian. Secure in their knowledge that the supernatural realm would always remain superior to the world of nature, leading Scholastic theologians had permitted this separation, effectively leaving society and cosmos to the interpretation of the new sciences. The Church had lost its grip on the culture, while within the community of believers the supernatural order, deprived of any intrinsic relationship to the natural, could only be imposed as it were by force – hence the tactics used to suppress Modernism.

The liturgical movement associated with the Second Vatican Council was closely related to the ressourcement. Yet it was influenced also by Rationalism on the one hand, and certain aspects of nineteenth-century Romanticism on the other. Fr Aidan Nichols described the confluence of these influences as follows:

If the Enlightenment insinuated into the stream of consciousness of practical liturgists such ambiguous notions as didacticism, naturalism, moral community-building, anti-devotionalism, and the desirability of simplification for its own sake, early Romanticism contributed such baleful notions as piety without dogma, reflecting the idea that man is a Gefühlswesen (what really matters is how you feel), a subjectivism different in kind from the Enlightenment's and more voracious, for anything and everything could be made to serve the production of the Romantic ego; an approach to symbolism that was aestheticist rather than genuinely ecclesial; and an enthusiasm for cosmic nature (Naturschwärmerei) that would see its final delayed offspring in the ëcreation-centered' spirituality of the 1980s."

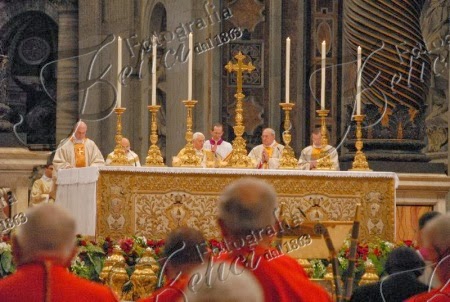

Aware of the growing gulf between faith and culture, linked to a division within the Church between a passive laity and an active clergy, the Church sought to "raze the bastions" and reach out to the world in the Second Vatican Council. Building on Pius XII's Mediator Dei the Council's Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy summed up many of the insights of the liturgical movement, most especially the fact that in the divine sacrifice of the Eucharist "the work of our redemption is accomplished" (2), implying the realism of the mystery of salvation in every Mass. This included an acknowledgement at the very outset that action should be subordinated to contemplation, the visible to the invisible. However, the Constitution gave particular prominence to the theme of "active participation" (participatio actuosa): "Mother Church earnestly desires that all the faithful should be led to that full, conscious and active participation in liturgical celebrations which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy" (14). To encourage this participation, the Constitution recommended simplification of the rites (34) on the one hand, and careful attention to the people's responses (acclamations, gestures, etc.) on the other (30).

The true meaning of the actio in which the Council Fathers intended the faithful to participate has been explained by Cardinal Ratzinger, most recently in his book The Spirit of the Liturgy. It is essentially an act of prayer. The Council was reacting against the view that prayer was something the faithful did on their own while the Mass was being celebrated by the priest. Nevertheless, the emphasis that the Council laid on the priest's responsibility to ensure this active participation on the part of the faithful in the liturgy as prayer did in practice give a great deal of weight to outward and vocal activity, which was observable, as distinct from the more important inner actio which this activity was supposed to promote.

It seems that those who were charged with the task of carrying out the reform in the name of the Council, far from transcending Rationalism and Romanticism, managed to perpetuate the worst elements of both. The functionalism and activism of the Rationalist tendency was married with a Romantic over-emphasis on community and feeling. The dualism of nature and grace was attacked, but not at its root. Clericalism was not overcome, but simply adopted another form. Intimations of transcendence ñ indeed, references to the soul ñ were minimized. Within the churches, walls were whitewashed and relics dumped in the name of "noble simplicity" (n. 34). Unlike the much earlier Cistercian rebellion against artistic extravagances at Cluny, this modern campaign for simplicity was not coupled with the asceticism and devotion that might alone have rendered it spiritually "noble". It fell easy victim to the prevailing culture of comfort and prosperity.

Loss of the Vertical Dimension

The misjudgments to which I am referring, and which have been extensively analysed elsewhere, were not able to affect the liturgical act itself or its validity, but they were serious enough to be accounted by many a disaster, and to provoke a schism. How did this disaster come about? A great part of the explanation must lie with the cultural moment. All earlier liturgies, Fr Nichols points out, "formed part of a culture itself ritual in character". The prevailing culture that began to emerge after the Second World War, far from being "ritual in character", was one in which ritual, hierarchy, reverence and custom were regarded with suspicion. Human freedom and creativity depend upon such rules and frameworks, not on liberation from them. A leading anthropologist writing at the end of the 1960s, Mary Douglas, argued that the contempt for ritual forms leads to the privatization of religious experience and thereby to secular humanism. The reformers were blithely unaware of such contemporary reappraisals of liturgy.

The very act of undertaking a far-reaching reform in these circumstances (however necessary a reform may have been) was bound to encourage an activist mentality that would regard itself as the master of the liturgy. Humble receptivity, so essential in matters of worship, was "put on hold" during the time it would take to make the desired changes. But a virtue once suspended is hard to revive. The reformist attitude showed itself in three particular ways. Firstly, having escaped from the kind of theological Rationalism that was associated with the old Scholastic manuals, they fell into the trap of historicist Rationalism. Pope Pius XII had warned against "archaeologism" in Mediator Dei, but the committees responsible for implementing Sacrosanctum Concilium appear to have chopped and trimmed, manipulated and manhandled the liturgy as though trying to reconstruct a primitive liturgy.

Secondly, as Casel, Bouyer, Guardini and others had insisted, the liturgical act is not only a prayer (for at least that much had been generally recognized) but also a mystery, in which something is done to us which we cannot fully understand, and which we must consent to and receive. The emphasis had swung towards didacticism, the endless preaching and explaining of the action of the liturgy. Over-simplified (and often patronizing) vernacular translations were intended to facilitate this. But in reality a sense of the sacred is essential to the act of worship, and is always inseparable from a sense of transcendence. Worship demands repentance and receptivity. Correctly understood, "active participation" in the liturgy is therefore no merely external activity, but rather an intensely active receptivity: the receiving and giving of the self in prayer.

Thirdly, the reformers' Modernistic rebellion against any kind of ordered, harmonious space separating sacred and profane was in fact a rebellion against the symbolism of space, and ultimately against all symbolism in the true sense. Symbols were to be reduced to the status of visual aids, in the service of a purely didactic rather than a sacramental ideal of liturgy. This was a rejection of sacred cosmology. With the loss of cosmic symbolism it was as though the vertical dimension of the liturgy had become inaccessible, and everything was concentrated on the horizontal plane, with an emphasis upon the cultivation of warm feelings among the congregation.

A fourth tendency has been mentioned by Cardinal Ratzinger on several occasions, namely the failure to understand the liturgy as a sacrifice – not as a separate sacrifice in addition to that of Calvary, or a "reconstruction" of the Passion, but as the self-same act performed once and for all, making present the sacrifice of the Cross "in an unbloody manner" throughout the Church, in diverse times and places. Thus the Mass was reduced to one of its aspects: that of a sacred meal, a celebratory feast.

The result of all these tendencies was a loss of liturgical beauty. Not that beauty per se is sacred: that would be the error of the aesthete. The deepest sense of beauty is the splendour of God's glory, perceived by the spiritual senses. Hans Urs von Balthasar has elucidated this in the first volume of his series The Glory of the Lord. Thus in New Elucidations he writes:

"God's glory, the majesty of his splendor, comes with its most precious gifts to us who are to ëpraise the glory of his grace' (Eph. 1:6). This last summons constitutes the norm and criterion for planning our liturgical services. It would be ridiculous and blasphemous to want to respond to the glory of God's grace with a counter-glory produced from our own creaturely reserves, in contrast to the heavenly liturgy that is portrayed for us in the Book of Revelation as completely dominated and shaped by God's glory. Whatever form the response of our liturgy takes, it can only be the expression of the most pure and selfless reception possible of the divine majesty of his grace; although reception, far from signifying something passive, is much rather than most active thing of which a creature is capable."

With the loss of the transcendent reference of the liturgy understood as a response to the divine glory, beauty is reduced to a purely subjective quality – a matter of personal taste – which is then easily swept aside in the interests of a more seemingly objective content: the moral lesson to be conveyed by the ritual. Thus, once again, we see the act of worship becoming didactic, moralizing, sentimental.

If the frustration of the reform was due in large measure to errors such as these, it can be understood and counteracted today only by attaining a deeper understanding of the true nature of the Catholic liturgy. The lesson of the liturgical reform is that the liturgy must ultimately be understood not in isolation, not in purely historical terms, not aesthetically, not sociologically, but ontologically, that is to say, in its full metaphysical and meta-anthropological depth.

Search for an Adequate Anthropology of the Liturgy

It was Pope John Paul II who set the Church on the road to an adequate anthropology, for example in his famous Wednesday catecheses on the book of Genesis, behind which lay earlier, more philosophical works such as The Acting Person and Love and Responsibility. This anthropology has most often been discussed in connection with the moral theology of the family. I will summarize it briefly, before trying to relate it to the liturgy.

The first point to make is that human will or free choice lies at the centre of the Pope's conception of man. This freedom, however, is founded on truth. To choose freely is "to make a decision according to the principle of truth". Truth is not something imposed arbitrarily from outside by the divine will, as it became for the Nominalists of the fourteenth century. It is normative precisely because it is intrinsic to the person, who must learn to choose in accordance with reality in order to achieve self-fulfilment. Thus the order of values or moral norms transcends the separation of subjective and objective which is characteristic of modern philosophy, because these norms are "personalistic": that is, intrinsic to the person. The Acting Person coins the term "reflexive" to describe our awareness of ourselves as the source of our actions. Reflexive consciousness is the condition of freedom. It is not the cognitive grasping of the self as object by the mediation of an idea, but the lived experience of being an acting person.

Secondly, the Pope recognizes that the particular nature of human action is that of an embodied creature rather than a pure spirit. The human person is a unity of soul and body, so that the truth which must be chosen is one that includes the reality of the body. Here the reflections of the philosopher Wojtyla are deepened by the Pope's meditation on Holy Scripture. The human creature is formed in what he calls "original solitude", a solitude that distinguishes him from all the other animals. This state of isolation is connected with the fact that man is only able to achieve fulfilment "through a sincere gift of himself". The aptitude for self-gift is what makes it impossible for Adam to find a suitable "helper" or companion among the animals. It isolates him, but at the same time it potentially opens him – to the Other, to the Woman, whom he greets with a cry of joy when she is brought to him for the first time. It is also this capacity for community, for communio, that constitutes his likeness to the trinitarian God. The self-giving of man, the fact that his heart is made to be given into the keeping of another, is an image of the divine processions: the generation of the Son, and his unity with the Father in the Holy Spirit who is "spirated" by both.

Thus the Pope recognizes our likeness to the Trinity not merely in the possession of freedom, but in "nuptiality"– in the physical difference of man and woman. The image of God is certainly in the soul, which images God as spirit. But the image of God as Trinity is found first and foremost in the nature of man as "male and female", and precisely in the nuptial relationship described in the second chapter of Genesis. And what is characteristic of the relationship of male to female, when compared with all other physical differences that exist between individuals, is that it is a difference that is specifically ordered towards the reproduction of life. Gender complementarity exists for the sake of procreation. Marriage partners are not merely turned towards one another: they are also oriented towards a potential third, towards the child which expresses the unity of both in one flesh. It is therefore an open relationship, not a closed or dualistic one. Angelo Scola describes the structure of this relationship as one of "asymmetrical reciprocity". Sexual difference is not overcome or cancelled out in the unity of marriage, because each spouse does not simply complete the other: he or she opens up new depths, new possibilities within the other. It is precisely in this respect that marriage mirrors the "dynamism" of the eternal perichoresis.

The anthropology that emerges through the writings of John Paul II is therefore marked by a nuptial and a trinitarian structure. The Pope's "Christian non-dualism" is not a denial of the legitimacy of Christian dualism, but it preserves dualism within a trinitarian dynamic. It is premised on the fact that all merely dualistic relationships are inherently unstable, and thus have a tendency to collapse into some form of monism. The sexual relationship, for example, if it is not open to new life, collapses into a form of narcissism. Connected with this is a strong sense of what is wrong with the act of contraception. To contracept is wrong because by acting against the being of the child who might otherwise come to exist through the act; it turns the relationship back into a dualistic one, no longer "asymmetrical" and no longer open to a mysterious "third person". It is to act (however unknowingly) not just against the potential child but against the presence within the marriage of the Holy Spirit, who is the Giver of Life.

Now we can turn back to the liturgy. What makes the connection is the fact that the mystery of the Mass has the same root as marriage, that nuptial mystery which is written into the essence of human nature. The marriage partners in this case are Christ the Bridegroom and his Bride the Church. The union between them is a covenant in the Holy Spirit. The liturgy enacts the marriage of the Lamb, combining the wedding banquet of the Last Supper with the redemptive act of the Passion. (On all of this one may read the seventh chapter of Mulieris Dignitatem, by Pope John Paul II.) Furthermore the trinitarian character of the Mass makes it "asymmetrical" in the same way that marriage is asymmetrical (cf. Ephesians 5:31-2). The "offspring" of this union are Christian souls, indwelt by the Holy Spirit.

Symbolic Realism and the Intelligence of the Heart

Resistance to the Pope's nuptial anthropology is deeply rooted. Rationalism cannot be overcome by mere intensity of sentiment. Romanticism cannot be overcome by more careful planning and calculation. We are caught in the dichotomy characteristic of Western thought since Descartes: the radical division between cold objectivity ("clear and distinct ideas") and unintelligent subjectivity. According to Christian "non-dualism", if two realities are to be united without losing their distinctiveness, they must find their unity in a third. If this is applied not to the relationship between persons, but to the human faculties within the individual, it suggests that reason and intuition, thought and feeling, may find their unity and fulfilment in a third faculty, the "intelligence of the heart" without which soul and body would not cohere to form a single hypostasis (and without which, therefore, the Incarnation itself would be impossible).

In his essay on "Tripartite Anthropology" in the collection Theology in History, Henri de Lubac traces the rise and fall in Christian tradition of the idea that man is composed not simply of body and soul, but of body, soul and spirit (1 Thess. 5:23). Of course, in much of the tradition the soul and spirit are treated as one, yet traces of the distinction remain, whether in St Teresa's reference to the "spirit of the soul" or (arguably) in St Thomas's intellectus agens. It is certainly present in The Philokalia, where the Eastern Fathers contrast the nous dwelling in the depths of the soul with the dianoia or discursive reason. Jean Borella also writes of this topic of the "human ternary", making clear its roots in the Old Testament. For the philosopher who became John Paul II, the "third" in question seems to be that "reflexive" consciousness by which we experience the drama of human existence as acting persons.

The spirit is the "place" within us where we receive the kiss of life from our Creator (Gen. 2:7), and where God makes his throne in the saints. Thus when St Paul appeals to the Romans (Rom. 12:1-2) to present their bodies as a living sacrifice in "spiritual worship" (logike latreia), he immediately continues: "Do not be conformed to this world but be transformed by the renewal of your mind [nous], that you may prove what is the will of God, what is good and well-pleasing and perfect." Paul implies that the "logic" of Christian worship – a logic of self-sacrifice that conforms us to the will of God – corresponds to a new intelligence. Discussions of the liturgy in the immediate postconciliar period may not have taken enough account of this fact with the results we have already noted.

As a natural faculty, even before it is "supernaturalized" by the indwelling of God's Holy Spirit at baptism, the spiritual intellect or apex mentis is the organ of metaphysics. It is recognized in all religious traditions, and the knowledge of universals which it gives (however distorted and confused after the Fall) is part of the common heritage of humanity. This is the faculty which perceives all things as symbolic in their very nature; that is, as expressing the attributes of God. The existence of God can be known from the things that are made; and the "book" of nature can be "read" according to the multiple aspects of the divine Wisdom present throughout creation. Thus Balthasar writes: "The whole world of images that surrounds us is a single field of significations. Every flower we see is an expression, every landscape has its significance, every human or animal face speaks its wordless language. It would be utterly futile to attempt a transposition of this language into concepts. Though we might try to circumscribe, even to describe, the content these things express, we would never succeed in rendering it adequately. This expressive language is addressed primarily, not to conceptual thought, but to the kind of intelligence that perceptively reads the gestalt of things."

Whatever name we give it ("intellect", "imagination" or "heart"), what Balthasar has in mind here is a faculty that transcends yet at the same time unifies feeling and thought, body and soul, sensation and rationality. It is the kind of intelligence that sees the meaning in things, that reads them as symbols – symbols, not of something else, but of themselves as they stand in God. Thus in the spiritual intelligence of man, being is unveiled in its true nature as a gift bearing within it the love of the Giver. Ultimately things ñ just as truly as persons ñ can be truly known only through love. In other words, a thing can be known only when it draws us out of ourselves, when we grasp it in its otherness from ourselves, in the meaning which it possesses as beauty, uniting truth and goodness. This kind of knowledge is justly called sobria ebrietas ("drunken" sobriety) because it is ecstatic, rapturous, although at the same time measured, ordered, dignified. It is an encounter with the Other which takes the heart out of itself and places it in another centre, which is ultimately the very centre of being, where all things are received from God.

All of this is implicit in the liturgy, the school where we learn this drunken sobriety, this intelligence of the heart. Its ABC is the language of natural symbols, such as water, light, oil and the gestures of the body, which the liturgy employs to speak of the sacramental mysteries unfolding within it. But symbols are far from being mere "visual aids", designed by the experts of the Church to communicate an idea or moral lesson that might more easily be conveyed in concepts to educated people. The Orthodox theologian Alexander Schmemann explains that the symbol is not merely an "illustration" but rather a genuine "manifestation": "We might say that the symbol does not so much ëresemble' the reality that it symbolizes as it participates in it, and therefore is capable of communicating it in reality". According to Schmemann also: "a sacrament is primarily a revelation of the [potential?] sacramentality of creation itself, for the world was created and given to man for conversion of creaturely life into participation in divine life."

Living the Liturgy

In the preceding two sections I have been suggesting that the "watermark" of the Trinity is found throughout all of creation at every level, wherever the identities of two things are preserved (and deepened) by uniting them in a third. Human and divine natures are united in the Person of the Son (Chalcedon). God and humanity are united in the sacrament of the Church (Vatican II). Man and woman are united in the "one flesh" of marriage. Reason and feeling are united in the intelligence of the heart.

Contrasted with this is the dualism which can only unite two things by absorbing one of them into the other. Dualism of this type afflicts the relationship of Church and world, priest and people, grace and nature, faith and culture, man and woman. It is the root both of clericalism and of secularism. The obvious conclusion from this analysis is that many seemingly unrelated problems in the Church have a common cause. The crisis over sexuality, brought into the open by the reaction to Humanae Vitae in 1968, stems from the mentality that fails to understand the true nature of the "asymmetric" relationship between man and woman. This is the same mentality that fails to understand the relationship between priest and people in the liturgy. This failure may express itself either in a clerical domination of the laity, or in a reversal of that relationship that eliminates all sense of the transcendent. On the one side, we find a poisonous cocktail of clericalism, aestheticism and misogyny. On the other, we observe "politically correct" liturgies devoted to the themes of justice and peace: everyone sitting in a circle, praying for the homeless and passing the consecrated chalice from hand to hand, with the priest improvising parts of the eucharistic prayer in order to make it more relevant and friendly.

Social charity cannot be reduced to a dualistic relationship without becoming either sentimental or domineering. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the liturgy gradually became separated from any living concern with social justice – or at least, it seems to have become hard to see the connection. Naturally, Christians were expected to go out from the liturgy and live virtuous lives, and thus have a transformative effect on society, but they did this by crossing from sacred space into secular space, rather than by discovering a deeper relationship between the two. This could be described as a profanization of charity; a secularization of solidarity. The post-conciliar reaction was to emphasize the horizontal dimension of the liturgy (social concern) over the vertical (the act of worship), or even to confuse the two. Whole religious orders went into steep decline as the communitarian aspect of their mission took precedence over the liturgical, the love of neighbour over the love of God. The problem of liberation theology was therefore a product not of the 1960s, but of the dualism of an earlier era.

Social solidarity is more securely grounded on right worship than on common feelings: the love of neighbour is founded on the love of God. This is in fact one of the clear implications, not only of the Ten Commandments themselves (the first three of which are devoted to the worship of God), but of the new Christian anthropology. The human person is by its very nature "trans-centric", or other-centred. We love God, and this opens us to the life of the other in our neighbour; we love our neighbour, and this opens us to the love of God. We do not simply go out to do good to another in the world, inspired by our worship of God in the church. Rather, the love of God sends us out to do good, because it reveals who we are and who is our neighbour. We are not (only) imitating the love of God that we see demonstrated in the liturgy, but living the liturgy out in the world. The liturgy is not (merely) separate in a horizontal sense from what goes on outside, but separate in the sense of being "interior", or revealing the inner meaning and purpose of what lies outside. Sacred space, sacred time and sacred art are distinctive, not (just) as belonging to a parallel world, but as defining the centre of this world: the world in which we live and work.

The secure possession of an authentic Christian anthropology thus reveals itself in the close involvement of the Church – whether as parish, as diocese, as religious order, as secular institute or as ecclesial movement – in forms of social action to relieve distress and to build a "culture of life". But it also reveals itself in more subtle ways: in the spirit with which the priest addresses the congregation, and the respect with which he is treated by them. He must lavish the same quality of attentiveness and devotion on the least of his brethren as he does on his rubrics and vestments on the one hand, and on the parish stalwarts on the other. Simone Weil once said that "prayer is attention", and we can make her words our own. The living prayer which is kindled in the liturgy – as it were from the Paschal candle at Eastertide – and without which the liturgy becomes an empty shell, involves a quality of loving attention which is directed towards that Other whom God has placed in our path, the Other who is a sign of the uniting Third, the Holy Spirit.

Conclusion

My intention in this paper was to steer a course between the clashing rocks of Rationalism and Romanticism. The modern temptation is to think that that the liturgy is something we can analyse "scientifically", with a view to controlling and perhaps improving it. Alternatively, we may think it nothing more than a collective celebration of togetherness to generate a strong community spirit. Here the rational and romantic approaches bring out the worst in each other. But with the awakening of the heart's intelligence, both approaches are transformed. The liturgy is understood from within, organically rather than mechanically. It is no longer a machine to be tinkered with, but a garden to be tended. The romantic tendency is also transformed. Feelings are rightly ordered towards the God who is our true centre because he is transcendent, and who is the giver of unity because he is other than ourselves.

Understood in this way the liturgy reveals us to ourselves, because it reveals "the mystery of the Father and his love" (in the famous words of Gaudium et Spes, 22). The Father's love is not a thing, not an object to be known and researched, but an act, a deed, an event, which may be known only through participation. In the Son, in the reception of his Gift which is the Holy Spirit and Redemption, we are broken open and poured out for the world, mingling our lives with his in the communion of the Church. Such talk makes no sense if the heart is not able to see the whole in the parts, the symbols as sacrament. But if the eye of the heart is opened, the world's true centre and purpose are unveiled. Our own identity as children of God, our "most high calling", is brought to light.

APPENDIX: Practical Implications for a New Liturgical Movement

The Centre for Faith & Culture organized an international conference on the liturgy in Oxford during 1996, in which the question of the "reform of the reform" was considered from a number of angles by a range of liturgical experts and organizations. The conclusions of the Liturgy Forum were expressed in "The Oxford Declaration on Liturgy", which was cited in parts of the Catholic press as reflecting a wide consensus among Catholics.

1. Reflecting on the history of liturgical renewal and reform since the Second Vatican Council, the Liturgy Forum agreed that there have been many positive results. Among these might be mentioned the introduction of the vernacular, the opening up of the treasury of the Sacred Scriptures, increased participation in the liturgy and the enrichment of the process of Christian initiation. However, the Forum concluded that the preconciliar liturgical movement as well as the manifest intentions of Sacrosanctum Concilium have in large part been frustrated by powerful contrary forces, which could be described as bureaucratic, philistine and secularist.

2. The effect has been to deprive the Catholic people of much of their liturgical heritage. Certainly, many ancient traditions of sacred music, art and architecture have been all but destroyed. Sacrosanctum Concilium gave pride of place to Gregorian chant [Section 116], yet in many places this "sung theology" of the Roman liturgy has disappeared without trace. Our liturgical heritage is not a superficial embellishment of worship but should properly be regarded as intrinsic to it, as it is also to the process of transmitting the Catholic faith in education and evangelization. Liturgy cannot be separated from culture; it is the living font of a Christian civilization and hence has profound ecumenical significance.

3. The impoverishment of our liturgy after the Council is a fact not yet sufficiently admitted or understood, to which the necessary response must be a revival of the liturgical movement and the initiation of a new cycle of reflection and reform. The liturgical movement which we represent is concerned with the enrichment, correction and resacralization of Catholic liturgical practice. It is concerned with a renewal of liturgical eschatology, cosmology and aesthetics, and with a recovery of the sense of the sacred – mindful that the law of worship is the law of belief. This renewal will be aided by a closer and deeper acquaintance with the liturgical, theological and iconographic traditions of the Christian East.

4. The revived liturgical movement calls for the promotion of the Liturgy of the Hours, celebrated in song as an action of the Church in cathedrals, parishes, monasteries and families, and of Eucharistic Adoration, already spreading in many parishes. In this way, the Divine Word and the Presence of Christ's reality in the Mass may resonate throughout the day, making human culture into a dwelling place for God. At the heart of the Church in the world we must be able to find that loving contemplation, that adoring silence, which is the essential complement to the spoken word of Revelation, and the key to active participation in the holy mysteries of faith [cf. Orientale Lumen, section 16].

5. We call for a greater pluralism of Catholic rites and uses, so that all these elements of our tradition may flourish and be more widely known during the period of reflection and ressourcement that lies ahead. If the liturgical movement is to prosper, it must seek to rise above differences of opinion and taste to that unity which is the Holy Spirit's gift to the Body of Christ. Those who love the Catholic tradition in its fullness should strive to work together in charity, bearing each other's burdens in the light of the Holy Spirit, and persevering in prayer with Mary the Mother of Jesus.

6. We hope that any future liturgical reform would not be imposed on the faithful but would proceed, with the utmost caution and sensitivity to the sensus fidelium, from a thorough understanding of the organic nature of the liturgical traditions of the Church [cf. Sacrosanctum Concilium, section 23]. Our work should be sustained by prayer, education and study. This cannot be undertaken in haste, or in anything other than a serene spirit. No matter what difficulties lie ahead, the glory of the Paschal Mystery – Christ's love, his cosmic sacrifice and his childlike trust in the Father – shines through every Catholic liturgy for those who have eyes to see, and in this undeserved grace we await the return of spring.

In the Declaration, several suggestions were made concerning the future of the liturgical reform: cultural enrichment, revival of the sense of the sacred and of contemplative prayer, restoration of plainsong, promotion of the liturgy of the hours and of eucharistic adoration, and acceptance of a "greater pluralism of Catholic rites and uses". It stressed the need to avoid any further mechanical tampering with the liturgy. The implication was that the liturgy should be permitted to develop organically.

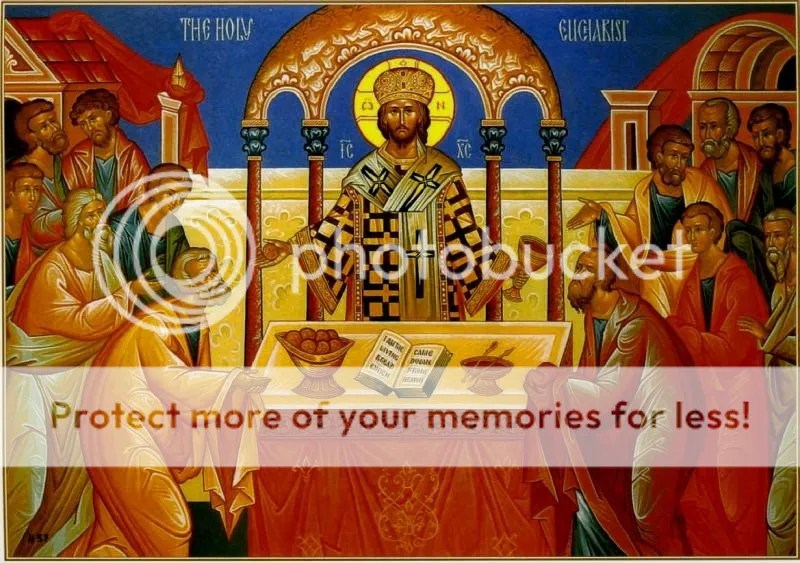

The Declaration also claimed that a revival of the liturgical movement would be aided by a "closer and deeper acquaintance with the liturgical, theological and iconographic traditions of the Christian East". It seems clear that in many ways the Byzantine tradition has maintained a greater sense of the sacred and of the cosmic dimensions of the liturgy than the Western tradition has been able to do. As a consequence, one observes the growing interest in the Eastern rites on the part of Westerners since the time of the Council. The popularity of Byzantine icons in the West is partly a healthy reaction against the widespread use of sentimentalized devotional images, but as the true greatness of the iconographic tradition gradually reveals itself lessons may be learnt concerning the liturgy too: the iconic properties of a ritual which manifests the action of Christ, compared to the iconic properties of a picture manifesting his presence, or the reality of his human nature. The point would not necessarily be to copy the Byzantine rite, but to develop the Roman rite to a point where the East can recognize in it an authentic Christian liturgy – which today is often not the case.

Clearly, further study and reflection are still needed to discern the principles that should govern any further reform of the liturgy. The present paper is one attempt to discover such principles. But a far-reaching programme of education is also needed, to accompany and make possible a reform of the reform. In another paper [see footnote 23 above] I have argued for reviving and extending the ancient practice of mystagogic catechesis, as part of the normal process of formation in the Christian mysteries. What is needed is a continuing education in the language of symbolism, in the spiritual meaning of the liturgy and of Holy Scripture, in the lives of the saints, and in the possibility of authentic and orthodox religious experience – the tradition of the spiritual senses, of lectio divina, of contemplative prayer, of ascesis and purity, of Catholic poetry and sacred art, and of the correct understanding and value of traditional devotions. The monastic practice of lectio divina has already become quite popular, but this should be increasingly integrated with a contemplative lectio of the Mass.

With this sole addition ñ the need for mystagogy ñ the Oxford Declaration perhaps may still stand today as an expression of the need felt by many for an authentic liturgical movement, faithful to the tradition of the Church, and submissive to the Holy Spirit who fills her with divine life.

Let Your Prayer Life Explode with Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity

by PATTI MAGUIRE ARMSTRONG

I know I should carve out more time for family and sleep. And prayer. Especially prayer.

If only I prayed more, then everything else would go smoother.

So I make the effort.

And then my phone rings. Or the dogs bark at something. Or… well, you get the picture.

Recently, however, something has changed for me. I’ve met Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity. She has inspired me not just to pray more, but to pray better.

St. John Paul II beatified Elizabeth in 1984, five years into his papacy. He identified her as one of the most influential mystics in his spiritual life. What does a cloistered Carmelite nun and mystic who died in 1906 at the age of 26 have to teach about navigating the modern world as a contemplative? Blessed Elizabeth understood that the Holy Spirit is timeless and holiness is an equal opportunity venture.

During the last months of her life, Blessed Elizabeth wrote down theological reflections that she believed would help people grow in prayer. She also wrote a 10-day retreat for her biological sister Margaret, a young mother. Blessed Elizabeth believed a contemplative life was possible for anyone who opened his or her heart. She wanted Catholics to enter deep into the mystery of God in order to have a transforming encounter with Christ and change the way they encountered the world.

Heaven in Faith

In the Beginning to Pray with Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity podcasts, Dr. Anthony Liles presents a 10-day spiritual retreat written by Blessed Elizabeth. Dr. Lilles is a Catholic husband and father of three who teaches Spiritual Theology at St. John Vianney Theological Seminary. His expertise is in the spiritual doctrine of Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity and the Carmelite Doctors of the Church: St. Teresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross and St. Thérèse of Lisieux. He is the author of Hidden Mountain, Secret Garden: A Theological Contemplation on Prayer.

The retreat has been called “Heaven in Faith.” Here is the first prayer of the first day with a brief summary of her reflection as explained by Dr. Lilles:

“‘Father, I will that where I am, they also whom you have given me may be with me in order that they may behold my glory which you have given me because you have loved me since before the creation of the world.’ Such is Christ’s last wish, his supreme prayer before returning to his Father. He wills that where he is we will be also. Not only for eternity but already in time which is eternity begun and still in progress. It is important then to know where we must live with him in order to realize his divine dream. The place where the Son of God is hidden is the bosom of the Father or the Divine Essence, invisible to every mortal eye, unattainable by every human intellect, as Isaiah said, ‘Truly you are a hidden God.’ And yet, his will is that we should be established in him, that we should live where he lives in the unity of love, that we should be, so to speak, his own shadow. By baptism, says St. Paul, we have been united to Jesus Christ. And again, God seeded us together in heaven in Christ Jesus, that he might show in the ages to come the riches of his grace, and further on, you are no longer guests or strangers but you belong to the city of saints and the house of God.”

The Supreme Desire of Jesus

In her reflections, Blessed Elizabeth explains that prayer is about an interpersonal communion of friendship, a kind of sharing of hearts with Jesus. She illuminates the deepest more supreme desire in the heart of Jesus given that the night before he died he prayed: “Father, I will that where I am, they also whom you have given me may be with me in order that they may behold my glory which you have given me because you have loved me since before the creation of the world.”

“Jesus desire is for us to be with him in communion. This is what he aches for, his deepest desire that he prays for. This is what Jesus was doing the night before he died.” Blessed Elizabeth calls this Jesus’s last wish, his supreme prayer. Out of this deep desire, he utters this prayer to the Father. She wants our hearts to be informed by this desire and to share this desire. “If we do, our spiritual lives and prayer will explode,” she wrote. “Our thoughts will be soaked with God. Because if we realize that if this is the Son of God—he is the word spoken by the father that has become flesh and this is Jesus’ deepest desire, it ought to evoke in us a desire that responds to it.”

Blessed Elizabeth wanted our faith to be to desire communion with God. That it is exactly what Jesus said he wants with us. We don’t have to take the afternoon off and bury ourselves in religious books and hours of prayer on our knees according to her. To be contemplative, she explained, we need to understand the simplicity of wanting to be united with Jesus and at the same time, the deepness. “Our omnipotent God, the creator of the World, wants most to be united with his poor limited frail creatures. He yearns for us to live with him.”

Blessed Elizabeth tapped into the understanding that we are made for something more than this world. In the midst of achievement, people are still empty, we are made for more, to dwell in union with God and God wants to dwell with us. When we live in unity with God, we have faith and we find our home with God. “The peace we were made to enjoy is found only by faith in Jesus Christ because Jesus Christ is the only one who can lead me into the bosom of the Trinity into the heart of the Father and in the heart of the Father my heart finds rest and I find the fullness of my humanity and the joy that God created me for becomes mine.”

The Filioque: A Church Dividing Issue?: An Agreed Statement

my source:

From 1999 until 2003, the North American Orthodox-Catholic Consultation has focused its discussions on an issue that has been identified, for more than twelve centuries, as one of the root causes of division between our Churches: our divergent ways of conceiving and speaking about the origin of the Holy Spirit within the inner life of the triune God. Although both of our traditions profess “the faith of Nicaea” as the normative expression of our understanding of God and God’s involvement in his creation, and take as the classical statement of that faith the revised version of the Nicene creed associated with the First Council of Constantinople of 381, most Catholics and other Western Christians have used, since at least the late sixth century, a Latin version of that Creed, which adds to its confession that the Holy Spirit “proceeds from the Father” the word Filioque: “and from the Son”. For most Western Christians, this term continues to be a part of the central formulation of their faith, a formulation proclaimed in the liturgy and used as the basis of catechesis and theological reflection. It is, for Catholics and most Protestants, simply a part of the ordinary teaching of the Church, and as such, integral to their understanding of the dogma of the Holy Trinity. Yet since at least the late eighth century, the presence of this term in the Western version of the Creed has been a source of scandal for Eastern Christians, both because of the Trinitarian theology it expresses, and because it had been adopted by a growing number of Churches in the West into the canonical formulation of a received ecumenical council without corresponding ecumenical agreement. As the medieval rift between Eastern and Western Christians grew more serious, the theology associated with the term Filioque, and the issues of Church structure and authority raised by its adoption, grew into a symbol of difference, a classic token of what each side of divided Christendom has found lacking or distorted in the other.

Our common study of this question has involved our Consultation in much shared research, prayerful reflection and intense discussion. It is our hope that many of the papers produced by our members during this process will be published together, as the scholarly context for our common statement. A subject as complicated as this, from both the historical and the theological point of view, calls for detailed explanation if the real issues are to be clearly seen. Our discussions and our common statement will not, by themselves, put an end to centuries of disagreement among our Churches. We do hope, however, that they will contribute to the growth of mutual understanding and respect, and that in God’s time our Churches will no longer find a cause for separation in the way we think and speak about the origin of that Spirit, whose fruit is love and peace (see Gal 5.22).

I. The Holy Spirit in the Scriptures

In the Old Testament “the spirit of God” or “the spirit of the Lord” is presented less as a divine person than as a manifestation of God’s creative power – God’s “breath” (ruach YHWH) - forming the world as an ordered and habitable place for his people, and raising up individuals to lead his people in the way of holiness. In the opening verses of Genesis, the spirit of God “moves over the face of the waters” to bring order out of chaos (Gen 1.2). In the historical narratives of Israel, it is the same spirit that “stirs” in the leaders of the people (Jud 13.25: Samson), makes kings and military chieftains into prophets (I Sam 10.9-12; 19.18-24: Saul and David), and enables prophets to “bring good news to the afflicted” (Is 61.1; cf. 42.1; II Kg 2.9). The Lord tells Moses he has “filled” Bezalel the craftsman “with the spirit of God,” to enable him to fashion all the furnishings of the tabernacle according to God’s design (Ex 31.3). In some passages, the “holy spirit” (Ps 51.13) or “good spirit” (Ps 143.10) of the Lord seems to signify his guiding presence within individuals and the whole nation, cleansing their own spirits (Ps. 51.12-14) and helping them to keep his commandments, but “grieved” by their sin (Is 63.10). In the prophet Ezekiel’s mighty vision of the restoration of Israel from the death of defeat and exile, the “breath” returning to the people’s desiccated corpses becomes an image of the action of God’s own breath creating the nation anew: “I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live...” (Ezek 37.14).

In the New Testament writings, the Holy Spirit of God (pneuma Theou) is usually spoken of in a more personal way, and is inextricably connected with the person and mission of Jesus. Matthew and Luke make it clear that Mary conceives Jesus in her womb by the power of the Holy Spirit, who “overshadows” her (Mt 1.18, 20; Lk 1.35). All four Gospels testify that John the Baptist – who himself was “filled with the Holy Spirit from his mother’s womb” (Lk 1.15) – witnessed the descent of the same Spirit on Jesus, in a visible manifestation of God’s power and election, when Jesus was baptized (Mt 3.16; Mk 1.10; Lk 3.22; Jn 1.33). The Holy Spirit leads Jesus into the desert to struggle with the devil (Mt 4.1; Lk 4.1), fills him with prophetic power at the start of his mission (Lk 4.18-21), and manifests himself in Jesus’ exorcisms (Mt 12.28, 32). John the Baptist identified the mission of Jesus as “baptizing” his disciples “with the Holy Spirit and with fire” (Mt 3.11; Lk 3.16; cf. Jn 1.33), a prophecy fulfilled in the great events of Pentecost (Acts 1.5), when the disciples were “clothed with power from on high” (Lk 24.49; Acts 1.8). In the narrative of Acts, it is the Holy Spirit who continues to unify the community (4.31-32), who enables Stephen to bear witness to Jesus with his life (8.55), and whose charismatic presence among believing pagans makes it clear that they, too, are called to baptism in Christ (10.47).

In his farewell discourse in the Gospel of John, Jesus speaks of the Holy Spirit as one who will continue his own work in the world, after he has returned to the Father. He is “the Spirit of truth,” who will act as “another advocate (parakletos)” to teach and guide his disciples (14.16-17), reminding them of all Jesus himself has taught (14.26). In this section of the Gospel, Jesus gives us a clearer sense of the relationship between this “advocate,” himself, and his Father. Jesus promises to send him “from the Father,” as “the Spirit of truth who proceeds from the Father” (15.26); and the truth that he teaches will be the truth Jesus has revealed in his own person (see 1,14; 14.6): “He will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you. All that the Father has is mine; therefore I said that he will take what is mine and declare it to you.” (16.14-15)

The Epistle to the Hebrews represents the Spirit simply as speaking in the Scriptures, with his own voice (Heb 3.7; 9.8). In Paul’s letters, the Holy Spirit of God is identified as the one who has finally “defined” Jesus as “Son of God in power” by acting as the agent of his resurrection (Rom 1.4; 8.11). It is this same Spirit, communicated now to us, who conforms us to the risen Lord, giving us hope for resurrection and life (Rom 8.11), making us also children and heirs of God (Rom 8.14-17), and forming our words and even our inarticulate groaning into a prayer that expresses hope (Rom 8.23-27). “And hope does not disappoint us because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to us.” (Rom 5.5)

II. Historical Considerations

Throughout the early centuries of the Church, the Latin and Greek traditions witnessed to the same apostolic faith, but differed in their ways of describing the relationship among the persons of the Trinity. The difference generally reflected the various pastoral challenges facing the Church in the West and in the East. The Nicene Creed (325) bore witness to the faith of the Church as it was articulated in the face of the Arian heresy, which denied the full divinity of Christ. In the years following the Council of Nicaea, the Church continued to be challenged by views questioning both the full divinity and the full humanity of Christ, as well as the divinity of the Holy Spirit. Against these challenges, the fathers at the Council of Constantinople (381) affirmed the faith of Nicaea, and produced an expanded Creed, based on the Nicene but also adding significantly to it.

Of particular note was this Creed’s more extensive affirmation regarding the Holy Spirit, a passage clearly influenced by Basil of Caesaraea’s classic treatise On the Holy Spirit, which had probably been finished some six years earlier. The Creed of Constantinople affirmed the faith of the Church in the divinity of the Spirit by saying: “and in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of life, who proceeds (ekporeuetai) from the Father, who with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified, who has spoken through the prophets.” Although the text avoided directly calling the Spirit “God,” or affirming (as Athanasius and Gregory of Nazianzus had done) that the Spirit is “of the same substance” as the Father and the Son – statements that doubtless would have sounded extreme to some theologically cautious contemporaries - the Council clearly intended, by this text, to make a statement of the Church’s faith in the full divinity of the Holy Spirit, especially in opposition to those who viewed the Spirit as a creature. At the same time, it was not a concern of the Council to specify the manner of the Spirit’s origin, or to elaborate on the Spirit’s particular relationships to the Father and the Son.

The acts of the Council of Constantinople were lost, but the text of its Creed was quoted and formally acknowledged as binding, along with the Creed of Nicaea, in the dogmatic statement of the Council of Chalcedon (451). Within less than a century, this Creed of 381 had come to play a normative role in the definition of faith, and by the early sixth century was even proclaimed in the Eucharist in Antioch, Constantinople, and other regions in the East. In regions of the Western churches, the Creed was also introduced into the Eucharist, perhaps beginning with the third Council of Toledo in 589. It was not formally introduced into the Eucharistic liturgy at Rome, however, until the eleventh century – a point of some importance for the process of official Western acceptance of the Filioque.

No clear record exists of the process by which the word Filioque was inserted into the Creed of 381 in the Christian West before the sixth century. The idea that the Spirit came forth “from the Father through the Son” is asserted by a number of earlier Latin theologians, as part of their insistence on the ordered unity of all three persons within the single divine Mystery (e.g., Tertullian, Adversus Praxean 4 and 5). Tertullian, writing at the beginning of the third century, emphasizes that Father, Son and Holy Spirit all share a single divine substance, quality and power (ibid. 2), which he conceives of as flowing forth from the Father and being transmitted by the Son to the Spirit (ibid. 8). Hilary of Poitiers, in the mid-fourth century, in the same work speaks of the Spirit as ‘coming forth from the Father’ and being ‘sent by the Son’ (De Trinitate 12.55); as being ‘from the Father through the Son’ (ibid. 12.56); and as ‘having the Father and the Son as his source’ (ibid. 2.29); in another passage, Hilary points to John 16.15 (where Jesus says: “All things that the Father has are mine; therefore I said that [the Spirit] shall take from what is mine and declare it to you”), and wonders aloud whether “to receive from the Son is the same thing as to proceed from the Father” (ibid. 8.20). Ambrose of Milan, writing in the 380s, openly asserts that the Spirit “proceeds from (procedit a) the Father and the Son,” without ever being separated from either (On the Holy Spirit 1.11.20). None of these writers, however, makes the Spirit’s mode of origin the object of special reflection; all are concerned, rather, to emphasize the equality of status of all three divine persons as God, and all acknowledge that the Father alone is the source of God’s eternal being. [Note: This paragraph includes a stylistic revision in the reference to Hilary of Poitiers that the Consultation agreed to at its October 2004 meeting.]

The earliest use of Filioque languagein a credal context is in the profession of faith formulated for the Visigoth King Reccared at the local Council of Toledo in 589. This regional council anathematized those who did not accept the decrees of the first four Ecumenical Councils (canon 11), as well as those who did not profess that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son (canon 3). It appears that the Spanish bishops and King Reccared believed at that time that the Greek equivalent of Filioque was part of the original creed of Constantinople, and apparently understood that its purpose was to oppose Arianism by affirming the intimate relationship of the Father and Son. On Reccared’s orders, the Creed began to be recited during the Eucharist, in imitation of the Eastern practice. From Spain, the use of the Creed with the Filioque spread throughout Gaul.

Nearly a century later, a council of English bishops was held at Hatfield in 680 under the presidency of Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury, a Byzantine asked to serve in England by Pope Vitalian. According to the Venerable Bede (Hist. Eccl. Gent. Angl. 4.15 [17]), this Council explicitly affirmed its faith as conforming to the five Ecumenical Councils, and also declared that the Holy Spirit proceeds “in an ineffable way (inenarrabiliter)” from the Father and the Son.

By the seventh century, three related factors may have contributed to a growing tendency to include the Filioque in the Creed of 381 in the West, and to the belief of some Westerners that it was, in fact, part of the original creed. First, a strong current in the patristic tradition of the West, summed up in the works of Augustine (354-430), spoke of the Spirit’s proceeding from the Father and the Son. (e.g., On the Trinity 4.29; 15.10, 12, 29, 37; the significance of this tradition and its terminology will be discussed below.) Second, throughout the fourth and fifth centuries a number of credal statements circulated in the Churches, often associated with baptism and catechesis. The formula of 381 was not considered the only binding expression of apostolic faith. Within the West, the most widespread of these was the Apostles’ Creed, an early baptismal creed, which contained a simple affirmation of belief in the Holy Spirit without elaboration. Third, however, and of particular significance for later Western theology, was the so-called Athanasian Creed (Quicunque). Thought by Westerners to be composed by Athanasius of Alexandria, this Creed probably originated in Gaul about 500, and is cited by Caesarius of Arles (+542). This text was unknown in the East, but had great influence in the West until modern times. Relying heavily on Augustine’s treatment of the Trinity, it clearly affirmed that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. A central emphasis of this Creed was its strong anti-Arian Christology: speaking of the Spirit as proceeding from the Father and the Son implied that the Son was not inferior to the Father in substance, as the Arians held. The influence of this Creed undoubtedly supported the use of the Filioque in the Latin version of the Creed of Constantinople in Western Europe, at least from the sixth century onwards.

The use of the Creed of 381 with the addition of the Filioque became a matter of controversy towards the end of the eighth century, both in discussions between the Frankish theologians and the see of Rome and in the growing rivalry between the Carolingian and Byzantine courts, which both now claimed to be the legitimate successors of the Roman Empire. In the wake of the iconoclastic struggle in Byzantium, the Carolingians took this opportunity to challenge the Orthodoxy of Constantinople, and put particular emphasis upon the significance of the term Filioque, which they now began to identify as a touchstone of right Trinitarian faith. An intense political and cultural rivalry between the Franks and the Byzantines provided the background for the Filioque debates throughout the eighth and ninth centuries.

Charlemagne received a translation of the decisions of the Second Council of Nicaea (787). The Council had given definitive approval to the ancient practice of venerating icons. The translation proved to be defective. On the basis of this defective translation, Charlemagne sent a delegation to Pope Hadrian I (772-795), to present his concerns. Among the points of objection, Charlemagne’s legates claimed that Patriarch Tarasius of Constantinople, at his installation, did not follow the Nicene faith and profess that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, but confessed rather his procession from the Father through the Son (Mansi 13.760). The Pope strongly rejected Charlemagne’s protest, showing at length that Tarasius and the Council, on this and other points, maintained the faith of the Fathers (ibid. 759-810). Following this exchange of letters, Charlemagne commissioned the so-called Libri Carolini (791-794), a work written to challenge the positions both of the iconoclast council of 754 and of the Council of Nicaea of 787 on the veneration of icons. Again because of poor translations, the Carolingians misunderstood the actual decision of the latter Council. Within this text, the Carolingian view of the Filioque also was emphasized again. Arguing that the word Filioque was part of the Creed of 381, the Libri Carolini reaffirmed the Latin tradition that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, and rejected as inadequate the teaching that the Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son.

While the acts of the local synod of Frankfurt in 794 are not extant, other records indicate that it was called mainly to counter a form of the heresy of “Adoptionism” then thought to be on the rise in Spain. The emphasis of a number of Spanish theologians on the integral humanity of Christ seemed, to the court theologian Alcuin and others, to imply that the man Jesus was “adopted” by the Father at his baptism. In the presence of Charlemagne, this council – which Charlemagne seems to have promoted as “ecumenical” (see Mansi 13.899-906) - approved the Libri Carolini, affirming, in the context of maintaining the full divinity of the person of Christ, that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. As in the late sixth century, the Latin formulation of the Creed, stating that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, was enlisted to combat a perceived Christological heresy.

Within a few years, another local council, also directed against “Spanish Adoptionism,” was held in Fréjus (Friuli) (796 or 797). At this meeting, Paulinus of Aquileia (+802), an associate of Alcuin in Charlemagne’s court, defended the use of the Creed with the Filioque as a way of opposing Adoptionism. Paulinus, in fact, recognized that the Filioque was an addition to the Creed of 381 but defended the interpolation, claiming that it contradicted neither the meaning of the creed nor the intention of the Fathers. The authority in the West of the Council of Fréjus, together with that of Frankfurt, ensured that the Creed of 381 with the Filioque would be used in teaching and in the celebration of the Eucharist in churches throughout much of Europe.

The different liturgical traditions with regard to the Creed came into contact with each other in early-ninth-century Jerusalem. Western monks, using the Latin Creed with the added Filioque, were denounced by their Eastern brethren. Writing to Pope Leo III for guidance, in 808, the Western monks referred to the practice in Charlemagne’s chapel in Aachen as their model. Pope Leo responded with a letter to “all the churches of the East” in which he declared his personal belief that the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son. In that response, the Pope did not distinguish between his personal understanding and the issue of the legitimacy of the addition to the Creed, although he would later resist the addition in liturgies celebrated at Rome.