One who climbs a mountain for the first time needs to follow a known route; and he needs to have with him, as companion and guide, someone who has been up before and is familiar with the way. To serve as such a companion and guide is precisely the role of the “Abba” or spiritual father—whom the Greeks call “Geron” and the Russians “Starets”, a title which in both languages means “old man” or “elder”. [1]

The importance of obedience to a Geron is underlined from the first emergence of monasticism in the Christian East. St. Antony of Egypt said: “I know of monks who fell after much toil and lapsed into madness, because they trusted in their own work ... So far as possible, for every step that a monk takes, for every drop of water that he drinks in his cell, he should entrust the decision to the Old Men, to avoid making some mistake in what he does.” [2]

This is a theme constantly emphasized in the Apophthegmata or Sayings of the Desert Fathers: “The old Men used to say: ‘if you see a young monk climbing up to heaven by his own will, grasp him by the feet and throw him down, for this is to his profit ... if a man has faith in another and renders himself up to him in full submission, he has no need to attend to the commandment of God, but he needs only to entrust his entire will into the hands of his father. Then he will be blameless before God, for God requires nothing from beginners so much as self-stripping through obedience.’” [3]

This figure of the Starets, so prominent in the first generations of Egyptian monasticism, has retained its full significance up to the present day in Orthodox Christendom. “There is one thing more important than all possible books and ideas”, states a Russian layman of the 19th Century, the Slavophile Kireyevsky, “and that is the example of an Orthodox Starets, before whom you can lay each of your thoughts and from whom you can hear, not a more or less valuable private opinion, but the judgement of the Holy Fathers. God be praised, such Startsi have not yet disappeared from our Russia.” And a Priest of the Russian emigration in our own century, Fr. Alexander Elchaninov (+ 1934), writes: “Their held of action is unlimited... they are undoubtedly saints, recognized as such by the people. I feel that in our tragic days it is precisely through this means that faith will survive and be strengthened in our country.” [4]

The Spiritual Father as a ‘Charismatic’ Figure

What entitles a man to act as a starets? How and by whom is he appointed?

To this there is a simple answer. The spiritual father or starets is essentially a ‘charismatic’ and prophetic figure, accredited for his task by the direct action of the Holy Spirit. He is ordained, not by the hand of man, but by the hand of God. He is an expression of the Church as “event” or “happening”, rather than of the Church as institution. [5]

There is, of course, no sharp line of demarcation between the prophetic and the institutional in the life of the Church; each grows out of the other and is intertwined with it. The ministry of the starets, itself charismatic, is related to a clearly-defined function within the institutional framework of the Church, the office of priest-confessor. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the right to hear confessions is not granted automatically at ordination. Before acting as confessor, a priest requires authorization from his bishop; in the Greek Church, only a minority of the clergy are so authorized.

Although the sacrament of confession is certainly an appropriate occasion for spiritual direction, the ministry of the starets is not identical with that of a confessor. The starets gives advice, not only at confession, but on many other occasions; indeed, while the confessor must always be a priest, the starets may be a simple monk, not in holy orders, or a nun, a layman or laywoman. The ministry of the starets is deeper, because only a very few confessor priests would claim to speak with the former’s insight and authority.

But if the starets is not ordained or appointed by an act of the official hierarchy, how does he come to embark on his ministry? Sometimes an existing starets will designate his own successor. In this way, at certain monastic centers such as Optina in 19th-century Russia, there was established an “apostolic succession” of spiritual masters. In other cases, the starets simply emerges spontaneously, without any act of external authorization. As Elchaninov said, they are “recognized as such by the people”. Within the continuing life of the Christian community, it becomes plain to the believing people of God (the true guardian of Holy Tradition) that this or that person has the gift of spiritual fatherhood. Then, in a free and informal fashion, others begin to come to him or her for advice and direction.

It will be noted that the initiative comes, as a rule, not from the master but from the disciples. It would be perilously presumptuous for someone to say in his own heart or to others, “Come and submit yourselves to me; I am a starets, I have the grace of the Spirit.” What happens, rather, is that—without any claims being made by the starets himself—others approach him, seeking his advice or asking to live permanently under his care. At first, he will probably send them away, telling them to consult someone else. Finally the moment comes when he no longer sends them away but accepts their coming to him as a disclosure of the will of God. Thus it is his spiritual children who reveal the starets to himself.

The figure of the starets illustrates the two interpenetrating levels on which the earthly Church exists and functions. On the one hand, there is the external, official, and hierarchial level, with its geographical organization into dioceses and parishes, its great centers (Rome, Constantinople, Moscow, and Canterbury), and its “apostolic succession” of bishops. On the other hand, there is the inward, spiritual and “charismatic” level, to which the startsi primarily belong. Here the chief centçrs are, for the most part, not the great primatial and metropolitan sees, but certain remote hermitages, in which there shine forth a few personalities richly endowed with spiritual gifts. Most startsi have possessed no exalted status in the formal hierarchy of the Church; yet the influence of a simple priest-monk such as St. Seraphim of Sarov has exceeded that of any patriarch or bishop in 19th-century Orthodoxy. In this fashion, alongside the apostolic succession of the episcopate, there exists that of the saints and spiritual men. Both types of succession are essential for the true functioning of the Body of Christ, and it is through their interaction that the life of the Church on earth is accomplished.

Flight and Return: the Preparation of the Starets

Although the starets is not ordained or appointed for his task, it is certainly necessary that he should be prepared.The classic pattern for this preparation, which consists in a movement of flight and return, may be clearly discerned in the liyes of St. Antony of Egypt (+356) and St. Seraphim of Sarov (+1833).

St. Antony’s life falls sharply into two halves, with his fifty-fifth year as the watershed. The years from, early manhood to the age of fifty-five were his time of preparation, spent in an ever-increasing seclusion from the world as he withdrew further and further into the desert. He eventually passed twenty years in an abandoned fort, meeting no one whatsoever. When he had reached the age of fifty-five, his friends could contain their curiosity no longer, and broke down the entrance. St. Antony came out and, ‘for the remaining half century of his long life, without abandoning the life of a hermit, he made himself freely available to others, acting as “a physician given by God to Egypt.” He was beloved by all, adds his biographer, St. Athanasius, “and all desired to ‘have him as their father.” [6] Observe that the transition from enclosed anchorite to Spiritual father came about, not through any initiative on St. Antony’s part, but through the action of others. Antony was a lay monk, never ordained to the priesthood.

St. Seraphim followed a comparable path. After fifteen years spent in the ordinary life of the monastic community, as novice, professed monk, deacon, and priest, he withdrew for thirty years of solitude and almost total silence. During the first part of this period he, lived in a forest hut; at one point he passed a thousand days on the stump of a tree and a thousand nights of those days on a rock, devoting himself to unceasing prayer. Recalled by his abbot to the monastery, he obeyed the order without the slightest delay; and during the latter part of his time of solitude he lived rigidly enclosed in his cell, which he did not leave even to attend services in church; on Sundays the priest brought communion to him at the door of his room. Though he was a priest he didn’t celebrate the liturgy. Finally, in the last eight years of his life, he ended his enclosure, opening the door of his cell and receiving all who came. He did nothing to advertise himself or to summon people; it was the others who took the initiative in approaching him, but when they came—sometimes hundreds or even thousands in a single day—he did not send them empty away.

Without this intense ascetic preparation, without this radical flight into solitude, could St. Antony or St. Seraphim have acted in the same ‘degree as guide to those of their generation? Not that they withdrew in order to become masters and guides of others. ‘They fled, not, in order to prepare themselves for some other task, but out of a consuming desire to be alone with God. God accepted their love, but then sent them back” as instruments of healing in the world from which they had withdrawn. Even had He never sent them back, their flight would still have been supremely creative and valuable to society; for the monk helps the world not primarily by anything that he does and says but by what he is, by the state of unceasing prayer which has become identical with his innermost being. Had St. Antony and St. Seraphim done nothing but pray in solitude they would still have been serving their fellow men to the highest degree. As things turned out, however, God ordained that they should also serve others in a more direct fashion. But this direct and visible service was essentially a consequence of the invisible service which they rendered through their prayer.

“Acquire inward peace”, said St. Seraphim, “and a multitude of men around you will find their salvation.” Such is the role of spiritual fatherhood. Establish yourself in God; then you can bring others to His presence. A man must learn to be alone, he must listen in the stillness of his own heart to the wordless speech of the Spirit, and so discover the truth about himself and God. Then his work to others will be a word of power, because it is a word out of silence.

What Nikos Kazantzakis said of the almond tree is true also of the starets: “I said to the almond tree, ‘Sister, speak to me of God,’ And the almond tree blossomed.”

Shaped by the encounter with God in solitude, the starets is able to heal by his very presence. He guides and forms others, not primarily by words of advice, but by his companionship, by the living and specific example which he sets—in a word, by blossoming like the almond tree. He teaches as much by his silence as by his speech. “Abba Theophilus the Archbishop once visited Scetis, and when the brethren had assembled they said to Abba Pambo, ‘Speak a word to the Pope that he may be edified.’ The Old Man said to them, ‘If he is not edified by my silence, neither will be he edified by my speech.’” [8] A story with the same moral is told of St. Antony. “It was the custom of three Fathers to visit the Blessed Antony once each year, and two of them used to ask him questions about their thoughts (logismoi) and the salvation of their soul; but the third remained completely silent, without putting any questions. After a long while, Abba Antony said to him, ‘See, you have been in the habit of coming to me all this time, and yet you do not ask me any questions’. And the other replied, ‘Father, it is enough for me just to look at you.’” [9]

The real journey of the starets is not spatially into the desert, but spiritually into the heart. External solitude, while helpful, is not indispensable, and a man may learn to stand alone before God, while yet continuing to pursue a life of active service in the midst of society. St. Antony of Egypt was told that a doctor in, Alexandria was his equal in spiritual achievement: “In the city there is someone like you, a doctor by profession, who gives all his money to the needy, and the whole day long he sings the Thrice-Holy Hymn with the angels.” [10] We are not told how this revelation came to Antony, nor what was the name of the doctor, but one thing is clear. Unceasing: prayer of the heart is no monopoly of the solitaries; the mystical and “angelic” life is possible in the city as well as the desert. The Alexandrian doctor accomplished the inward journey without severing his outward links with the community.

There are also many instances in which flight and return are not sharply distinguished in temporal sequence. Take, for example, the case of St. Seraphim’s younger contemporary, Bishop Ignaty Brianchaninov (t1867). Trained originally as an army officer, he was appointed at the early age of twenty-six to take charge of a busy and influential monastery close to St. Petersburg. His own monastic training had lasted little more than four years before he was placed in a position of authority. After twetity-four years as Abbot, he was consecrated Bishop. Four years later he resigned, to spend the remaining six years of his life as a hermit. Here a period of active pastoral work preceded the period of anachoretic seclusion. When he was made abbot, he must surely have felt gravely ill-prepared. His secret withdrawal into the heart was undertaken continuously during the many years in which he administered a monastery and a diocese; but it did not receive an exterior, expression until the very end of his life.

Bishop Ignaty’s career [11] may serve as a paradigm to many of us at the present time, although (needless to say) we fall far short of his level of spiritual achievement. Under the pressure of outward circumstances and probably without clearly realizing what is happening to us, we become launched on a career of teaching, preaching, and pastoral counselling, while lacking any deep knowledge of the desert and its creative silence. But through teaching others we ourselves begin to learn. Slowly we recognize our powerlessness to heal the wounds of humanity solely through philanthropic programs, common sense, and psychiatry. Our complacency is broken down, we appreciate our own inadequacy, and start to understand what Christ meant by the “one thing that is necessary” (Luke 10:42). That is the moment when we enter upon the path of the starets. Through our pastoral experience, through our anguish over the pain of others,’ we are brought to undertake the journey inwards, to ascend the secret ladder of the Kingdom, where alone a genuine solution to the world’s problems can be found. No doubt few if any among us would think of ourselves as a starets in the full sense, but provided we seek with humble sincerity to enter into the “secret chamber” of our heart, we can all share to some degree in the grace of the spiritual fatherhood. Perhaps we shall never outwardly lead the life of a monastic recluse or a hermit—that rests with God—but what is supremely important is that each should see the need to be a hermit of the heart.

The Three Gifts of the Spiritual Father

Three gifts in particular distinguish the spiritual father. The first is insight and discernment (diakrisis), the ability to perceive intuitively the secrets of another’s heart, to understand the hidden depths of which the other is unaware. The spiritual father penetrates beneath the conventional gestures and attitudes whereby we conceal our true personality from others and from ourselves; and beyond all these trivialities, he comes to grips with the unique person made in the image and likeness of God. This power is spiritual rather than psychic; it is not simply a kind of extra-sensory perception or a sanctified clairvoyance but the fruit of grace, presupposing concentrated prayer and an unremitting ascetic struggle.

With this gift of insight there goes the ability to use words with power. As each person comes before him, the starets knows—immediately and specifically—what it is that the individual needs to hear. Today, we are inundated with words, but for the most part these are conspicuously not words uttered with power. [12] The starets uses few words, and sometimes none at all; but by these few words or by his silence, he is able to alter the whole direction of a man’s life. At Bethany, Christ used three words only: “Lazarus, come out” (John 11:43) and these three words, spoken with power, were sufficient to bring the dead back to life. In an age when language has been disgracefully trivialized, it is vital to rediscover the power of the word; and this means rediscovering the nature of silence, not just as a pause between words but as one of the primary realities of existence. Most teachers and preachers talk far too much; the starets is distinguished by an austere economy of language.

But for a word to possess power, it is necessary that there should be not only one who speaks with the genuine authority of personal experience, but also one who listens with attention and eagerness. If someone questions a starets out of idle curiosity, it is likely that he will receive little benefit; but if he approaches the starets with ardent faith and deep hunger, the word that he hears may transfigure his being. The words of the startsi are for the most part simple in verbal expression and devoid of literary artifice; to those who read them in a superficial way, they will seem jejune and banal.

The spiritual father’s gift of insight is exercised primarily through the practice known as “disclosure of thoughts” (logismoi). In early Eastern monasticism the young monk used to go daily to his father and lay before him all the thoughts which had come to him during the day. This disclosure of thoughts includes far more than a confession of sins, since the novice also speaks of those ideas and impulses which may seem innocent to him, but in which the spiritual father may discern secret dangers or significant signs. Confession is retrospective, dealing with sins that have already occurred; the disclosure of thoughts, on the other hand, is prophylactic, for it lays bare our logismoi before they have led to sin and so deprives them of their, power to harm. The purpose of the disclosure is not juridical, to secure absolution from guilt, but self-knowledge, that each may see himself as he truly is. [13]

Endowed with discernment, the spiritual father does not merely wait for a person to reveal himself, but shows to the other thoughts hidden from him. When people came to St. Seraphim of Sarov, he often

answered their difficulties before they had time to put their thoughts before him. On many occasions the answer at first seemed quite irrelevant, and even absurd and irresponsible; for what St. Seraphim answered was not, the question his visitor had consciously in mind, but the one he ought to have been asking. In all this St. Seraphim relied on the inward light of the Holy Spirit. He found it important, he explained, not to work out in advance hat he was going to say; in that case, his words would represent merely his own human judgment which might well be in error, and not the judgment of God.

In St. Seraphim’s eyes, the relationship between starets and spiritual child is stronger than death, and he therefore urged his children to continue their disclosure of thoughts to him even after his departure to the next life. These are the words which, by his on command, were written on his tomb: “When I am dead, come to me at my grave, and the more often, the better. Whatever is on your soul, whatever may have happened to you, come to me as when I was alive and, kneeling on the ground, cast all your bitterness upon my grave. Tell me everything and I shall listen to you, and all the bitterness will fly away from you. And as you spoke to me when I was alive, do so now. For I am living, and I shall be forever.”

The second gift of the spiritual father is the ability to love others and to make others’ sufferings his own. Of Abba Poemen, one of the greatest of the Egyptian gerontes, it is briefly and simply recorded: “He possessed love, and many came to him.” [14] He possessed love—this is indispensable in all spiritual fatherhood. Unlimited insight into the secrets of men’s hearts, if devoid of loving compassion, would not be creative but destructive; he who cannot love others will have little power to heal them.

Loving others involves suffering with and for them; such is the literal sense of compassion. “Bear one anothers burdens and so fulfill the law of Christ” (Galatians 6:2). The spiritual father is ‘the one who par excellence bears the burdens of others. “A starets”, writes Dostoevsky in The Brothers Karamazov, “is one who takes your soul, your will, unto his soul and his will.... ” It is not enough for him to offer advice. He is also required to take up the soul of his spiritual children into his own soul, their life into his life. It is his task to pray for them, and his constant intercession on their behalf is more important to them than any words of counsel. [15] It is his task likewise to assume their sorrows and their sins, to take their guilt upon himself, and to answer for them at the Last Judgment.

All this is manifest in a primary document of Eastern spiritual direction, the Books of Varsanuphius and John, embodying some 850 questions addressed to two elders of 6th-century Palestine, together with their written answers. “As God Himself knows,” Varsanuphius insists to his spiritual children, “there is not a second or an hour when I do not have you in my mind and in my prayers ... I care for you more than you care for yourself ... I would gladly lay down my life for you.” This is his prayer to God: “O Master, either bring my children with me into Your Kingdom, or else wipe me also out of Your book.” Taking up the theme of bearing others’ burdens, Varsanuphius affirms: “I am bearing your burdens and your offences ... You have become like a man sitting under a shady tree ... I take upon myself the sentence of condemnation against you, and by the grace of Christ, I will not abandon you, either in this age or in the Age to Come.” [16]

Readers of Charles Williams will be reminded of the principle of ‘substituted love,’ which plays a central part in Descent into Hell. The same line of thought is expressed by Dostoevsky’s starets Zosima: “There is only one way of salvation, and that is to make yourself responsible for all men’s sins... To make yourself responsible in all sincerity for everything and for everyone.” The ability of the starets to support and strengthen others is measured by his willingness to adopt this way of salvation.

Yet the relation between the spiritual father and his children is not one-sided. Though he takes the burden of their guilt upon himself and answers for them before God, he cannot do this effectively unless they themselves are struggling wholeheartedly for their own salvation. Once a brother came to St. Antony of Egypt and said: “Pray for me.” But the Old Man replied: “Neither will I take pity on you nor will God, unless you make some effort of your own.” [17]

When considering the love of a starets for those under his care, it is important to give full meaning to the word “father” in the title “spiritual father”. As father and offspring in an ordinary family should be joined in mutual love, so it must also be within the “charismatic” family of the starets. It is primarily a relationship in the Holy Spirit, and while the wellspring of human affection is not to be unfeelingly suppressed, it must be contained within bounds. It is recounted how a young monk looked after his elder, who was gravely ill, for twelve years without interruption. Never once in that period did his elder thank him or so much as speak one word of kindness to him. Only on his death-bed did the Old Man remark to the assembled brethren, “He is an angel and not a man.” [18] The story is valuable as an indication of the need for spiritual detachment, but such an uncompromising suppression of all outward tokens of affection is not typical of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, still less of Varsanuphius and John.

A third gift of the spiritual father is the power to transform the human environment, both the material and the non-material. The gift of healing, possessed by so many of the startsi, is one aspect of this power: More generally, the starets helps his disciples to perceive the world as God created it and as God desires it once more to be. “Can you take too much joy in your Father’s works?” asks Thomas Traherne. “He is Himself in everything.” The true starets is one who discerns this universal presence of the Creator throughout creation, and assists others to discern it. In the words of William Blake, “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything will appear to man as it is, infinite.” For the man who dwells in God, there is nothing mean and trivial: he sees everything in the light of Mount Tabor. “What is a merciful heart?” inquires St. Isaac the Syrian. “It is a heart that burns with love for ‘the whole of creation—for men, for the birds, for the beasts, for the demons, for every, creature. When a man with such a heart as this thinks of the creatures or looks at them, his eyes are filled with tears; An overwhelming compassion makes his heart grow! small and weak, and he cannot endure to hear or see any suffering, even the smallest pain, inflicted upon any creature. Therefore he never ceases to pray, with tears even for the irrational animals, for the enemies of truth, and for those who do him evil, asking that they may be guarded and receive God’s mercy. And for the reptiles also he prays with a great compassion, which rises up endlessly in his heart until he shines again and is glorious like God.”’ [19]

An all-embracing love, like that of Dostoevsky’s starets Zosima, transfigures its object, making the human environment transparent, so that the uncreated energies of God shine through it. A momentary glimpse of what this transfiguration involves is provided by the celebrated conversation between St. Seraphim of Sarov and Nicholas Motovilov, his spiritual child. They were walking in the forest one winter’s day and St. Seraphim spoke of the need to acquire the Holy Spirit. This led Motovilov to ask how a man can know with certainty that he is “in the Spirit of God':

Then Fr. Seraphim took me very firmly by the shoulders and said: “My son, we are both, at this moment in the Spirit of God. Why don’t you look at me?”

“I cannot look, Father,” I replied, “because your eyes are flashing like lightning. Your face has become brighter than the sun, and it hurts my eyes to look, at you.”

“Don’t be afraid,” he said. “At this very moment you have yourself become as bright as I am. You are yourself in the fullness of the Spirit of God at this moment; otherwise you would not be able to see me as you do... but why, my son, do you not look me iii the eyes? Just look, and don’t be afraid; the Lord is with us.”

After these words I glanced at his face, and there came over me an even greater reverent awe. Imagine in the center of the sun, in the dazzling light of its mid-day rays, the face of a man talking to you. You see the movement of his lips and the changing expression of his eyes and you hear his voice, you feel someone holding your shoulders, yet you do not see his hands, you do not even see yourself or his body, but only a blinding light spreading far around for several yards and lighting up with its brilliance the snow-blanket which covers the forest glade and the snowflakes which continue to fall unceasingly [20].

Obedience and Freedom

Such are by God’s grace, the gifts of the starets. But what of the spiritual child? How does he contribute to the mutual relationship between father and son in God?

Briefly, what he offers is his full and unquestioning obedience. As a classic example, there is the story in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers about the monk who was told to plant a dry stick iii the sand and to water it daily. So distant was the spring from his cell that he had to leave in the evening to fetch the water and he only returned in the following morning. For three years he patiently fulfilled his Abba’s command. At the end of this period, the stick suddenly put forth leaves and bore fruit. The Abba picked the fruit, took it to the church, and invited the monks to eat, saying, “Come and taste the fruit of obedience.” [21]

Another example of obedience is the monk Mark who was summoned by his Abba, while copying a manuscript, and so immediate was his response that he did not even complete the circle of the letter that he was writing. On another occasion, as they walked together, his Abba saw a small pig; testing Mark, he said, “Do you see that buffalo, my child?” “Yes, Father,” replied Mark. “And you see how powerful its horns are?” “Yes, Father”, he answered once more without demur. [22] Abba Joseph of Panepho, following a similar policy, tested the obedience of his disciples by assigning ridiculous tasks to them, and only if they complied would he then give them sensible commands. [23] Another geron instructed his disciple to steal things from the cells of the brethren; [24] yet another told his disciple (who had not been entirely truthful with him) to throw his son into the furnace. [25]

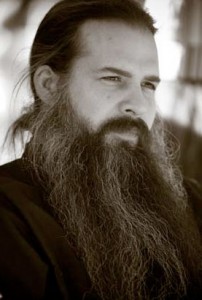

Father John of Kronstadt and his spiritual daughter

Such stories are likely to make a somewhat ambivalent impression on the modern reader. They seem to reduce the disciple to an infantile or sub-human level, depriving him of all power of judgment and moral choice. With indignation we ask: “Is this the ‘glorious liberty of the children of God’?” (Rom. 8:21)

Three points must here be made. In the first place, the obedience offered by the spiritual son to his Abba is not forced but willing and voluntary. It is the task of the starets to take up our will into his will, but he can only do this if by our own free choice we place it in his hands. He does not break our will, but accepts it from us as a gift. A submission that is forced and involuntary is obviously devoid of moral value; the starets asks of each one that he offer to God his heart, not his external actions.

The voluntary nature of obedience is vividly emphasized in the ceremony of the tonsure at the Orthodox rite of monastic profession. The scissors are placed upon the Book of the Gospels, and the novice must himself pick them up and give them to the abbot. The abbot immediately replaces them on the Book of the Gospels. Again the novice take the scissors, and again they are replaced. Only when the novice him the scissors for the third time does the abbot proceed to cut hair. Never thereafter will the monk have the right to say to the abbot or the brethren: “My personality is constricted and suppressed here in the monastery; you have deprived me of my freedom”. No one has taken away his freedom, for it was he himself who took up the scissors and placed them three times in the abbot’s hand.

But this voluntary offering of our freedom is obviously something that cannot be made once and for all, by a single gesture; There must be a continual offering, extending over our whole life; our growth in Christ is, measured precisely by the increasing degree of our self-giving. Our freedom must be offered anew each day and each hour, in constantly varying ways; and this means that the relation between starets and disciple is not static but dynamic, not unchanging but infinitely diverse. Each day and each hour, under the guidance of his Abba, the disciple will face new situations, calling for a different response, a new kind of self-giving.

In the second place, the relation between starets and spiritual child is not one- but two-sided. Just as the starets enables the disciples to see themselves as they truly are, so it is the disciples who reveal the starets to himself. In most instances, a man does not realize that he is called to be a starets until others come to him and insist on placing themselves under his guidance. This reciprocity continues throughout the relationship between the two. The spiritual father does not possess an exhaustive program, neatly worked out in advance and imposed in the same manner upon everyone. On the contrary, if he is a true starets, he will have a different word for each; and since the word which he gives is on the deepest level, not his own but the Holy Spirit’s, he does not know in advance what that word will be. The starets proceeds on the basis, not of abstract rules but of concrete human situations. He and his disciple enter each situation together; neither of them knowing beforehand exactly what the outcome will be, but each waiting for the enlightenment of the Spirit. Each of them, the spiritual father as well as the disciple, must learn as he goes.

The mutuality of their relationship is indicated by certain stories in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, where an unworthy Abba has a spiritual son far better than himself. The disciple, for example, detects his Abba in the sin of fornication, but pretends to have noticed nothing and remains under his charge; and so, through the patient humility of his new disciple, the spiritual father is brought eventually to repentance and a new life. In such a case, it is not the spiritual father who helps the disciple, but the reverse. Obviously such a situation is far from the norm, but it indicates that the disciple is called to give as well as to receive.

In reality, the relationship is not two-sided but triangular, for in addition to the starets and his disciple there is also a third partner, God. Our Lord insisted that we should call no man “father,” for we have only one father, who is in Heaven (Matthew 13:8-10). The starets is not an infallible judge or a final court of appeal, but a fellow-servant of the living God; not a dictator, but a guide and companion on the way. The only true “spiritual director,” in the fullest sense of the word, is the Holy Spirit.

This brings us to the third point. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition at its best, the spiritual father has always sought to avoid any kind of constraint and spiritual violence in his relations with his disciple. If, under the guidance of the Spirit, he speaks and acts with authority, it is with the authority of humble love. The words of starets Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov express an essential aspect of spiritual fatherhood: “At some ideas you stand perplexed, especially at the sight of men’s sin, uncertain whether to combat it by force or by humble love. Always decide, ‘I will combat it by humble love.’ If you make up your mind about that once and for all, you can conquer the whole world. Loving humility is a terrible force; it is the strongest of all things and there is nothing like it.”

Anxious to avoid all mechanical constraint, many spiritual fathers in the Christian East refused to provide their disciples with a rule of life, a set of external commands to be applied automatically. In the words of a contemporary Romanian monk, the starets is “not a legislator but a mystagogue.” [26] He guides others, not by imposing rules, but by sharing his life with them. A monk told Abba Poemen, “Some brethren have come to live with me; do you want me to give them orders?” “No,” said the Old Man. “But, Father,” the monk persisted, “they themselves want me to give them orders.” “No”, repeated Poemen, “be an example to them but not a lawgiver.” [27] The same moral emerges from the story of Isaac the Priest. As a young man, he remained first with Abba Kronios and then with Abba Theodore of Pherme; but neither of them told him what to do. Isaac complained to the other monks and they came and remonstrated with Theodore. “If he wishes”, Theodore replied eventually, “let him do what he sees me doing.” [28] When Varsanuphius was asked to supply a detailed rule of life, he refused, saying: “I do not want you to be under the law, but under grace.” And in other letters he wrote: “You know that we have never imposed chains upon anyone... Do not force men’s free will, but sow in hope, for our Lord did not compel anyone, but He preached the good news, and those who wished hearkened to Him.” [29]

Do not force men’s free will. The task of the spiritual father is not to destroy a man’s freedom, but to assist him to see the truth for himself; not to suppress a man’s personality, but to enable him to discover himself, to grow to full maturity and to become what he really is. If on occasion the spiritual father requires an implicit and seemingly “blind” obedience from his disciple, this is never done as an end in itself, nor with a view to enslaving him. The purpose of this kind of shock treatment is simply to deliver the disciple from his false and illusory “self”, so that he may enter into true freedom. The spiritual father does not impose his own ideas and devotions, but he helps the disciple to find his own special vocation. In the words of a 17th-century Benedictine, Dom Augustine Baker: “The director is not to teach his own way, nor indeed any determinate way of prayer, but to instruct his disciples how they may themselves find out the way proper for them ... In a word, he is only God’s usher, and must lead souls in God’s way, and not his own.” [30]

In the last resort, what the spiritual father gives to his disciple is not a code of written or oral regulations, not a set of techniques for meditation, but a personal relationship. Within this personal relationship the Abba grows and changes as well as the disciple, for God is constantly guiding them both. He may on occasion provide his disciple with detailed verbal instructions, with precise answers to specific questions. On other occasions he may fail to give any answer at all; either because he does not think that the question needs an answer, or because he himself does not yet know what the answer should be. But these answers—or this failure to answer—are always given the framework of a personal relationship. Many things cannot be said in words, but can be conveyed through a direct personal encounter.

In the Absence of a Starets

And what is one to do, if he cannot find a spiritual father?

He may turn, in the first place, to books. Writing in 5th-century Russia, St. Nil Sorsky laments the extreme scarcity of qualified spiritual directors; yet how much more frequent they must have been in his day than in ours! Search diligently, he urges, for a sure and trustworthy guide. “However, if such a teacher cannot be found, then the Holy Fathers order us to turn to the Scriptures and listen to Our Lord Himself speaking.” [31] Since the testimony of Scripture should not be isolated from the continuing witness of the Spirit in the life of the Church, the inquirer will also read the works of the Fathers, and above all the Philokalia. But there is an evident danger here. The starets adapts his guidance to the inward state of each; books offer the same advice to everyone. How is the beginner to discern whether or not a particular text is applicable to his own situation? Even if he cannot find a spiritual father in the full sense, he should at least try to find someone more experienced than himself, able to guide him in his reading.

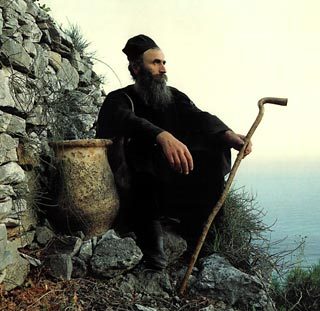

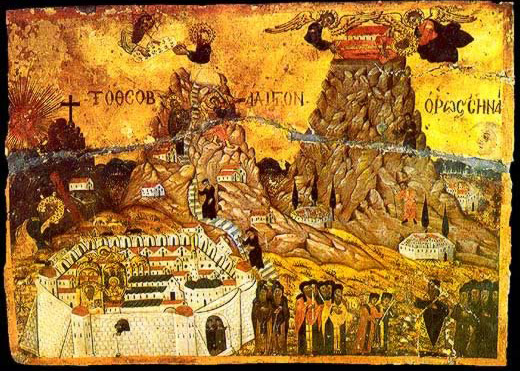

It is possible to learn also from visiting places where divine grace has been exceptionally manifested and where prayer has been especially concentrated. Before taking a major decision, and in the absence of other guidance, many Orthodox Christians will goon pilgrimage to Jerusalem or Mount Athos, to some monastery or the tomb of a saint, where they will pray for enlightenment. This is the way in which I have reached the more difficult decisions in my life.

Thirdly, we can learn from religious communities with an established tradition of the spiritual life. In the absence of a personal teacher, the monastic environment can serve as guru; we can receive our formation from the ordered sequence of the daily program, with its periods of liturgical and silent prayer, with its balance of manual labor, study, and recreation. [32] This seems to have be en the chief way in which St. Seraphim of Sarov gained his spiritual training. A well-organized monastery embodies, in an accessible and living form, the inherited wisdom of many starets. Not only monks, but those who come as visitors for a longer or shorter period, can be formed and guided by the experience of community life.

It is indeed no coincidence that the kind of spiritual fatherhood that we have been describing emerged initially in 4th-century Egypt, not within the fully organized communities under St. Pachomius, but among the hermits and in the semi-eremitic milieu of Nitria and Scetis. In the former, spiritual direction was provided by Pachomius himself, by the superiors of each monastery, and by the heads of individual “houses” within the monastery. The Rule of St. Benedict also envisages the abbot as spiritual father, and there is no provision for further development of a more “charismatic” type. In time, of course, the coenobitic communities incorporated many of the traditions of spiritual fatherhood as developed among the hermits, but the need for those traditions has always been less intensely felt in the coenobia, precisely because direction is provided by the corporate life pursued under the guidance of the Rule.

Finally, before we leave the subject of the absence of the starets, it is important to recognize the extreme flexibility in the relationship between starets and disciple. Some may see their spiritual father daily or even hourly, praying, eating, and working with him, perhaps sharing the same cell, as often happened in the Egyptian Desert. Others may see him only once a month or once a year; others, again, may visit a starets on but a single occasion in their entire life, yet this will be sufficient to set them on the right path. There are, furthermore, many different types of spiritual father; few will be wonder-workers like St. Seraphim of Sarov. There are numerous priests and laymen who, while lacking the more spectacular endowments of the startsi, are certainly able to provide others with the guidance that they require.

Many people imagine that they cannot find a spiritual father, because they expect him to be of a particular type: they want a St. Seraphim, and so they close their eyes to the guides whom God is actually sending to them. Often their supposed problems are not so very complicated, and in reality they already know in their own heart what the answer is. But they do not like the answer, because it involves patient and sustained effort on their part: and so they look for a deus ex machina who, by a single miraculous word, will suddenly make everything easy. Such people need to be helped to an understanding of the true nature of spiritual direction.

Contemporary Examples

In conclusion, I wish briefly to recall two startsi of our own day, whom I have had the happiness of knowing personally. The first is Father Amphilochios (+1970), abbot of the Monastery of St. John on the Island of Patmos, and spiritual father to a community of nuns which he had founded not far from the Monastery. What most distinguished his character was his gentleness, the warmth of his affection, and his sense of tranquil yet triumphant joy. Life in Christ, as he understood it, is not a heavy yoke, a burden to be carried’ with resignation, but a personal relationship to be pursued with eagerness of heart. He was firmly opposed to all spiritual violence and cruelty. It was typical that, as he lay dying and took leave of the nuns under his care, he should urge the abbess not to be too severe on them: “They have left everything to come here, they must not be unhappy.” [33] When I was to return from Patmos to England as a newly-ordained priest, he insisted that there was no need to be afraid of anything.

My second example is Archbishop John (Maximovich), Russian bishop in Shanghai, in Western Europe, and finally in San Francisco (+1966). Little more than a dwarf in height, with tangled hair and beard, and with an impediment in his speech, he possessed more than a touch of the “Fool in Christ.” From the time of his profession as a monk, he did not lie down on a bed to sleep at night; he went on working and praying, snatching his sleep at odd moments in the 24 hours. He wandered barefoot through the streets of Paris, and once he celebrated a memorial, service among the tram lines close to the port of Marseilles. Punctuality had little meaning for him. Baffled by his unpredictable behavior, the more conventional among his flock sometimes judged him to be unsuited for the administrative work of a bishop. But with his total disregard of normal formalities he succeeded where others, relying on worldly influence and expertise, had failed entirely—as when, against all hope and in the teeth of the “quota” system, he secured the admission of thousands of homeless Russian refugees to the U.S.A.

In private conversation he was very gentle, and he quickly won the confidence of small children. Particularly striking was the intensity of his intercessory prayer. When possible, he liked to celebrate the Divine Liturgy daily, and the service often took twice or three times the normal space of time, such was the multitude of those whom he commemorated individually by name. As he prayed for them, they were never mere names on a lengthy list, but always persons. One story that I was told is typical. It was his custom each year to visit Holy Trinity Monastery at Jordanville, N.Y. As he left, after one such visit, a monk gave him a slip of paper with four names of those who were gravely ill. Archbishop John received thousands upon thousands of such requests for prayer in the course of each year. On his return to the monastery some twelve months later, at once he beckoned to the monk, and much to the latter’s surprise, from the depths of his cassock Archbishop John produced the identical slip of paper, now crumpled and tattered. “I have been praying for your friends,” he said, “but two of them”—he pointed to their names—'are now dead and the other two have recovered.” And so indeed it was.

Even at a distance he shared in the concerns of his spiritual children. One of them, superior of a small Orthodox monastery in Holland, was sitting one night in his room, unable to sleep from anxiety over the problems which faced him. About three o’dock in the morning, the telephone rang; it was Archbishop John, speaking from several hundred miles away. He had rung to say that it was time for the monk to go to bed.

Such is the role of the spiritual father. As Varsanuphius expressed it, “I care for you more than you care for yourself.”

Endnotes

1. On spiritual fatherhood in the Christian East, see the well-documented study by I. Hausherr, S. L., Direction Spintuelle en Orient d’Autrefois (Orientalia Christiana Analecta, 144: Rome 1955). An excellent portrait of a great starets in 19th-century Russia is provided by J. B. Dunlop, Staretz Amvrosy: Model for Dostoevsky’s Staretz Zossima (Belmont, Mass. 1972); compare also I. de Beausobre, Macanus, Starets of Optina: Russian Letters of Direction 1834-1860 (London, 1944). For the life and writings of a Russian starets in the present century, see Archimandrite Sofrony, The Undistorted Image. Staretz Silouan: 1866-1938 (London, 1958).

2. Apophthegmata Patrum, alphabetical collection (Migne, P.G., 65, pp. 37-8).

3. Les Apophtegemes des Pères du Desert, by J. C. Guy, S.jj. (Textes de Spiritualité Orientale, No. 1: Etiolles, 1968), pp. 112, 158.

4. A. Elchaninov, The Diary of a Russian Priest, (London, 1967, p. 54).

5. I use “charismatic” in the restricted sense customarily given to it by contemporary writers. But if that word indicates one who has received the gifts or charismata of the Holy Spirit, then the ministerial priest, ordained through the episcopal laying on of hands, is as genuinely a “charismatic” as one who speaks with tongues.

6. The Life of St. Antony, chapters 87 and 81 (P.G. 26, 965A, and 957A.)

7. Quoted in Igumen Chariton, The Art of Prayer: An Orthodox Anthology (London, 1966), p. 164. [Webmaster Note: I could not determine where this footnote appeared in the original article.]

8. Apophthegmata Patrum, alphabetical collection, Theophilus the Archbishop, p. 2. In the Christian East, the Patriarch of Alexandria bears the title “Pope.”

9. Ibid., Antony p. 27.

10. Ibid., Antony, p. 24.

11. Compare Ignaty’s contemporary, Bishop Theophan the Recluse (+l894) and St. Tikhon of Zadonsk (+l753).

12. Three of the great banes of the 20th century are shorthand, duplicators and photocopying machines. If chairmen of committees and those in seats of authority were forced to write out personally in longhand everything they wanted to communicate to others, no doubt they would choose their words with greater care.

13. Evergetinos, Synagoge, 1, 20 (ed. Victor Matthaiou, I, Athens, 1957, pp. 168-9).

14. Apophthegmata Patrum, alphabetical collection, Poemen, p. 8.

15. For the importance of a spiritual father’s prayers, see for example Les Apophtegmes des Peres du Désert, tr. Guy, “série des dits anonymes”, P. 160.

16. The Book of Varsanuphius and John, edited by Sotirios Schoinas (Volos, 1960), pp. 208, 39, 353, 110 and 23g. A critical edition of part of the Greek text, accompanied by an English translation, has been prepared by D. J. Chitty: Varsanuphius and John, Questions and Answers, (Patrologia Orientalis, XXXI, 3, Paris, 1966). [This and many other fine books on spiritual direction are available from St. Herman Press.—OCIC Ed.

17. Apophthegmata Patrurn, alphabetical collection, Antony, p. 16.

18. Ibid., John the Theban, p. 1.

19. Mystic Treatises of Isaac of Nineveh, tr. by A. J. Wensinck, (Amsterdam, 1923), p. 341.

20. “Conversation of St. Seraphim on the Aim of the Christian Life,” in A Wonderful Revelation to the World (Jordanville, N.Y., 1953), pp. 23-24.

21. Apophthegmata Patrum, alphabetical collection, John Colobos, p. 1.

22. Ibid., Mark the Disciple of Silvanus, pp. 1, 2.

23. Ibid., Joseph of Panepho, p. 5.

24. Ibid., Saio, p. 1. The geron subsequently returned the things to their rightful owners.

25. Les Apophtegmes des Peres du Desert, tr. Guy, “serie des dits anonymes,” p. 162. There is a parallel story in the alphabetical collection, Sisoes, p. 10; cf. Abraham and Isaac (Gen. 22).

26. Fr. André Scrima, “La Tradition du Père Spirituel dan l’Eglise d’Orient.” Hermes, 1967, No. 4, p. 83.

27. Apophthegmata Patrurn, alphabetical collection, Poemen, p. 174.

28. Ibid., Isaac the Priest, p. 2.

29. The Book of Varsanuphius and John, pp. 23, 51, 35.

30. Quoted by Thomas Merton, Spiritual Direction and Meditation. (1960), p. 12.

31. “The Monastic Rule,” in G. P. Fedotov, A Treasury of Russian Spirituality, (London, 1950) p.96.

32. See Thomas Merton, op. cit., pp. 14-16, on the dangers of rigid monastic discipline without proper spiritual direction.

33. See I. Gorainoff, “Holy Men of Patmos”, Sobornost (The Journal of the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius), Series 6, No. 5 (1972) pp. 341-4.

From Cross Currents (Summer/Fall 1974), pp. 296-313.