A first-class commentary of Lossky's "The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church", putting it in context:

↧

ORTHODOX TALKS ON MONASTICISM AND PRAYER

↧

HOW TO ENTER INTO THE TIME AND SPACE OF GOD: CELEBRATING THE FEAST OF SAINTS CYRIL & METHODIUS

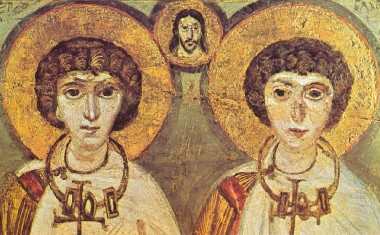

SS. CYRIL AND METHODIUS

mi fuente: La Enciclopedia Católica

These brothers, the Apostles of the Slavs, were born in Thessalonica, in 827 and 826 respectively. Though belonging to a senatorial family they renounced secular honours and became priests. They were living in a monastery on the Bosphorous, when the Khazars sent to Constantinople for a Christian teacher. Cyril was selected and was accompanied by his brother. They learned the Khazar language and converted many of the people. Soon after the Khazar mission there was a request from the Moravians for a preacher of the Gospel. German missionaries had already laboured among them, but without success. The Moravians wished a teacher who could instruct them and conduct Divine service in the Slavonic tongue. On account of their acquaintance with the language, Cyril and Methodius were chosen for their work. In preparation for it Cyril invented an alphabet and, with the help of Methodius, translated the Gospels and the necessary liturgical books into Slavonic. They went to Moravia in 863, and laboured for four and a half years. Despite their success, they were regarded by the Germans with distrust, first because they had come from Constantinople where schism was rife, and again because they held the Church services in the Slavonic language. On this account the brothers were summoned to Rome by Nicholas I, who died, however, before their arrival. His successor, Adrian II, received them kindly. Convinced of their orthodoxy, he commended their missionary activity, sanctioned the Slavonic Liturgy, and ordained Cyril and Methodius bishops. Cyril, however, was not to return to Moravia. He died in Rome, 4 Feb., 869.

At the request of the Moravian princes, Rastislav and Svatopluk, and the Slav Prince Kocel of Pannonia, Adrian II formed an Archdiocese of Moravia and Pannonia, made it independent of the German Church, and appointed Methodius archbishop. In 870 King Louis and the German bishops summoned Methodius to a synod at Ratisbon. Here he was deposed and condemned to prison. After three years he was liberated at the command of Pope John VIII and reinstated as Archbishop of Moravia. He zealously endeavoured to spread the Faith among the Bohemians, and also among the Poles in Northern Moravia. Soon, however, he was summoned to Rome again in consequence of the allegations of the German priest Wiching, who impugned his orthodoxy, and objected to the use of Slavonic in the liturgy. But John VIII, after an inquiry, sanctioned the Slavonic Liturgy, decreeing, however, that in the Mass the Gospel should be read first in Latin and then in Slavonic. Wiching, in the meantime, had been nominated one of the suffragan bishops of Methodius. He continued to oppose his metropolitan, going so far as to produce spurious papal letters. The pope, however, assured Methodius that they were false. Methodius went to Constantinople about this time, and with the assistance of several priests, he completed the translation of the Holy Scriptures, with the exception of the Books of Machabees. He translated also the "Nomocanon", i.e. the Greek ecclesiastico-civil law. The enemies of Methodius did not cease to antagonize him. His health was worn out from the long struggle, and he died 6 April, 885, recommending as his successor Gorazd, a Moravian Slav who had been his disciple.

Formerly the feast of Saints Cyril and Methodius was celebrated in Bohemia and Moravia on 9 March; but Pius IX changed the date to 5 July. Leo XIII, by his Encyclical "Grande Munus" of 30 September, 1880, extended the feast to the universal Church. [Note: The feast of Sts. Cyril and Methodius is currently celebrated on February 14 in the Latin Church.]

Saints Cyril and Methodius are two of the greatest missionaries in church history, as well as being patron saints of Europe. They also should be patron saints of Vatican II, of those who revised the Latin Rite and had it translated into modern languages, as well as of all those who are striving to continue perfecting the new Mass according to the mind of Popes Benedict XVI and Francis. That mind is well expressed below. - Fr David

How to Enter into the Time and Space of God

Pope Francis makes a surprise break with his silence on the liturgy. "It is the cloud of God that envelops us all," he says. And he calls for a return to the true sense of the sacred by Sandro Magister

ROME, February 14, 2014 – Fifty years after the promulgation of the document of Vatican Council II on the liturgy, the Vatican is solemnizing the event with a three-day conference at the pontifical university of the Lateran, organized by the congregation for divine worship from the 18th to the 20th of this month.

So far the liturgy has not seemed to be one of the top priorities in the vision of Pope Francis. In the long interview-confession with "La Civiltà Cattolica" last summer he reduced the conciliar liturgical reform to this dismissive definition: " a service to the people as a re-reading of the Gospel from a concrete historical situation."

Not a word more, if not for the "worrying risk of the ideologization of the Vetus Ordo, its exploitation."

But on Monday, February 10, with no forewarning Jorge Mario Bergoglio broke the silence and dedicated to the liturgy the entire homily of the morning Mass in the chapel of Santa Marta. Saying things he has never said before, since he became pope.

That morning the passage was read from the first book of Kings in which during the reign of Solomon the cloud, the divine glory, filled the temple and "the Lord decided to dwell in the cloud."

Taking his cue from that "theophany," pope Jorge Mario Bergoglio said that "in the Eucharistic liturgy God is present" in a way even "closer" than in the cloud in the temple, his "is a real presence."

And he continued:

"When I speak of the liturgy I am mainly referring to the holy Mass. The Mass is not a representation, it is something else. It is living once again the redemptive passion and death of the Lord. It is a theophany: the Lord makes himself present on the altar in order to be offered to the Father for the salvation of the world."

Further on the pope said:

"The liturgy is the time of God and space of God, and we must put ourselves there in the time of God, in the space of God, and not look at our watches. The liturgy is nothing less than entering into the mystery of God, allowing ourselves to be carried to the mystery and to be in the mystery. It is the cloud of God that envelops us all."

And looking back on one of his childhood memories:

"I recall that as a child, when they were preparing us for first communion, they had us sing: 'O holy altar guarded by the angels,' and this made us understand that the altar was truly guarded by the angels, it gave us the sense of the glory of God, of the space of God, of the time of God."

Coming to the conclusion, Francis invited those present to "ask the Lord today to give all of us this sense of the sacred, this sense that makes us understand that it is one thing to pray at home, to pray the rosary, to pray many beautiful prayers, make the way of the cross, read the bible, and the Eucharistic celebration is another thing. In the celebration we enter into the mystery of God, into that path which we cannot control. He alone is the one, he is the glory, he is the power. Let us ask for this grace: that the Lord may teach us to enter into the mystery of God."

_________

The February 10 homily of Pope Francis in the summary provided by "L'Osservatore Romano":

__________

The constitution of Vatican Council II on the liturgy, the first of the documents approved by that assembly:

> Sacrosanctum Concilium

__________

And this is how Benedict XVI spoke of it in his improvised talk with the clergy of Rome on February 14, 2013, exactly one year ago, one of the very last acts of his pontificate:

"After the First World War, Central and Western Europe had seen the growth of the liturgical movement, a rediscovery of the richness and depth of the liturgy, which until then had remained, as it were, locked within the priest’s Roman Missal, while the people prayed with their own prayer books, prepared in accordance with the heart of the people, seeking to translate the lofty content, the elevated language of classical liturgy into more emotional words, closer to the hearts of the people. But it was as if there were two parallel liturgies: the priest with the altar-servers, who celebrated Mass according to the Missal, and the laity, who prayed during Mass using their own prayer books, at the same time, while knowing substantially what was happening on the altar.

"But now there was a rediscovery of the beauty, the profundity, the historical, human, and spiritual riches of the Missal and it became clear that it should not be merely a representative of the people, a young altar-server, saying 'Et cum spiritu tuo', and so on, but that there should truly be a dialogue between priest and people: truly the liturgy of the altar and the liturgy of the people should form one single liturgy, an active participation, such that the riches reach the people. And in this way, the liturgy was rediscovered and renewed.

"I find now, looking back, that it was a very good idea to begin with the liturgy, because in this way the primacy of God could appear, the primacy of adoration. 'Operi Dei nihil praeponatur': this phrase from the Rule of Saint Benedict (cf. 43:3) thus emerges as the supreme rule of the Council. Some have made the criticism that the Council spoke of many things, but not of God. It did speak of God! And this was the first thing that it did, that substantial speaking of God and opening up all the people, the whole of God’s holy people, to the adoration of God, in the common celebration of the liturgy of the Body and Blood of Christ. In this sense, over and above the practical factors that advised against beginning straight away with controversial topics, it was, let us say, truly an act of Providence that at the beginning of the Council was the liturgy, God, adoration. Here and now I do not intend to go into the details of the discussion, but it is worth while to keep going back, over and above the practical outcomes, to the Council itself, to its profundity and to its essential ideas.

"I would say that there were several of these: above all, the Paschal Mystery as the centre of what it is to be Christian – and therefore of the Christian life, the Christian year, the Christian seasons, expressed in Eastertide and on Sunday which is always the day of the Resurrection. Again and again we begin our time with the Resurrection, our encounter with the Risen one, and from that encounter with the Risen one we go out into the world. In this sense, it is a pity that these days Sunday has been transformed into the weekend, although it is actually the first day, it is the beginning; we must remind ourselves of this: it is the beginning, the beginning of Creation and the beginning of re-Creation in the Church, it is an encounter with the Creator and with the Risen Christ. This dual content of Sunday is important: it is the first day, that is, the feast of Creation, we are standing on the foundation of Creation, we believe in God the Creator; and it is an encounter with the Risen One who renews Creation; his true purpose is to create a world that is a response to the love of God.

"Then there were the principles: intelligibility, instead of being locked up in an unknown language that is no longer spoken, and also active participation. Unfortunately, these principles have also been misunderstood. Intelligibility does not mean banality, because the great texts of the liturgy – even when, thanks be to God, they are spoken in our mother tongue – are not easily intelligible, they demand ongoing formation on the part of the Christian if he is to grow and enter ever more deeply into the mystery and so arrive at understanding. And also the word of God – when I think of the daily sequence of Old Testament readings, and of the Pauline Epistles, the Gospels: who could say that he understands immediately, simply because the language is his own? Only ongoing formation of hearts and minds can truly create intelligibility and participation that is something more than external activity, but rather the entry of the person, of my being, into the communion of the Church and thus into communion with Christ."

__________

English translation by Matthew Sherry, Ballwin, Missouri, U.S.A.

__________

↧

↧

WHEN WE ENTER A CHURCH WE ENTER THE TIME AND SPACE OF GOD (POPE FRANCIS). WHAT IS A CHURCH AND WHY?

The church is holy because it houses the gathered Church; and the altar is holy because it is on this table that Mass is celebrated. The real church is the Christian community: the building is only a "church" by association. Realising this has led many to conclude that the value of the church building lies only in its function, and that it is not a holy place as the Temple in Jerusalem was holy: only the community is holy, the building an optional extra. This has been reflected in the architecture of churches which often look like secular buildings; and movements like the neo-catechumenists often prefer to celebrate the Eucharist outside church buildings. After all, the earliest christians had no church buildings. If Le Corbusier defined a house as a "machine for living in", many modern churches look very much like "machines for praying in", without any holiness of their own.

In this post I am going to argue that this is contrary to Catholic Tradition, that even the least holy parts of a Catholic church are superior in their level of holiness to anything in the Jerusalem Temple, including the Holy of Holies.

In Old Testament times, God entered a sinful world, and there was an enormous contrast between places associated with God´s presence and the rest of the world, beween the sacred and the profane; and nowhere was as holy as the Holy of Holies. It was so holy that the High Priest entered it with trepidation, just in case God should manifest himself and the High Priest should die, because "no one can see God and live."

In New Testament times, the Temple is replaced by Christ´s body and by Christians who share his body and in the Spirit; but this does not mean that the there are no sacred places or things. The very contrary is true; and they are all over the place. Wherever the Christian life is lived becomes holy by association, far holier than any pre-Christian site. To believe otherwise shows a lack of appreciation for the meaning and effects of the Incarnation.

Genesis gives a cosmic role to Adam and Eve, naming all the animals, giving meaning to Creation. They were that part of Creation that walked with God in the cool of the evening. They were made in his image, and so became the means by which God's holiness poured out on Creation, as well as being Creation's voice by which it prayed to and praised the Lord. That is why Adam's fall was of cosmic importance, messing up everything.

Salvation, putting things right, is not just about souls: it is about restoring God's proper relationship to Creation as a whole, making it transparent to his divine Presence - making it holy - through the activity of Christians who share by the Incarnation in the very life of God.

Places are always holy to the degree that God is active in them; and things are holy to the degree that God uses them. God works in and through the Church and its members. Thus prisons and places of torture become holy because in them Christian martyrs have suffered and died; hospitals become holy because Gods loves the patients through the sisters that run them; the streets of Calcutta became holy through the activity of Mother Teresa's sisters; Christian homes become holy because of the Christian life that is nurtured there; music becomes holy to the extent that its beauty reflects the divine Glory. Most obvious of all, churches are holy because God acts at every level of church life.

It is the function of Church art to manifest the reality that it reflects. Whatever the style, a church that does not look like a church is a failure from the very start.

Recently, Pope Francis said in a homily:

"The liturgy is the time of God and space of God, and we must put ourselves there in the time of God, in the space of God, and not look at our watches. The liturgy is nothing less than entering into the mystery of God, allowing ourselves to be carried to the mystery and to be in the mystery. It is the cloud of God that envelops us all."

It is the function of Christian architecture and art to reflect this reality and mediate it to those who take part in the liturgy. Salvation in Christ restores to the Church and its members the means to sanctify places and things we use in the Lord's service, because we become Christ's instruments. Only at the Second Coming will the whole cosmos be holy in that way; but we Christians have a foretaste. Because of it, God's revelation, which comes to us as a Word, directed at our hearing, takes a myriad os shapes, directed to all our senses. Thus we say with St John:

We declare to you what was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life - this life was revealed, and we have seen itThrough art and the Christian life, we not only listen to God's message: He communicates to us through all our senses. Thus, Pope Benedict has said:

“I did once say that to me art and the saints are the greatest apologetics for our faith.”

It was Pope Benedict’s love of baroque art and architecture that is such a revelation for English-speaking Catholics. He explains that

“in line with the tradition of the West, the Council [of Trent] again emphasised the didactic and pedagogical character of art, but, as a fresh start toward interior renewal, it led once more to a new kind of seeing that comes from and returns within. The altarpiece is like a window through which the world of God comes out to us. The curtain of temperately is raised, and we are allowed a glimpse into the inner life of the world of God. This art is intended to insert us into the liturgy of heaven. Again and again, we experience a Baroque church as a unique kind of fortissimo of joy, an Alleluia in visual form.”

THE HOLINESS OF A CATHOLIC CHURCH AS EXPRESSED IN THE LITURGY OF THE DEDICATION OF A CHURCH OR AN ALTAR.

The church is holy because it houses the gathered Church; and the altar is holy because it is on this table that Mass is celebrated. Let us now look at what the liturgy has to say about the sanctity of a church, using as our chief source the Rite for the Dedication of a Church and the Rite for a Dedication of an Altar. What hits us immediately is the preliminary statement of the bishop to the people at the dedication of a church or an altar. On greeting the people, the bishop should say something like:

Brothers and sisters in Christ, this is a day of rejoicing: we have come to dedicate this church (this altar) by offering the sacrifice of Christ.(for a church) May we open our hearts and minds to receive his word with faith; may our fellowship born in the one font of baptism and sustained at the one table of the Lord, become the one temple of his Spirit, as we gather round his altar in love.

(for an altar) May we respond to these holy rites, receive God’s word with faith, share at the Lord’s table with joy, and raise up our hearts in hope.

We belong to the New Covenant in which all religious institutions of the Old Testament have been replaced by people. Christ is the temple, the priesthood, the only victim and the altar, and has also replaced the Law of Moses as the Way (). The Blessed Virgin Mary is the Ark of the New Covenant; and, when she was by Christ’s side while he was dying on the cross, she embraced both her Son and the whole human race in her love, and thus she came to represent all those down the ages whose synergy with the Holy Spirit would make them one with Christ on the cross: At the foot of the cross she was personally the Church in its relationship to Christ, the New Eve, and Mother of all the living.. As our icon depicts, she is personally what the Church is collectively: she is the Bride of the Lamb.. No longer is God’s dwelling place among the people on earth a building. Since Christ’s Ascension, the temple has been replaced by us who are participants in Christ; we are his body, the Church, in whom God dwells bodily, reconciling the world to himself. By participating in the Eucharistic fellowship we become “the one temple of his Spirit”. In the Old Testament, the covenanted presence of God depended on the temple and the fulfilment of the purification ritual on the Day of the Atonement; and the altar sanctified the offering so that it could be offered on no other altar; and hence the crisis when the temple was destroyed. In New Testament times, in contrast, it is the presence of God’s People that sanctifies the church; and it is the offering by Christ of himself that sanctifies our offering and the altar on which it is placed.

If we were neo-scholastics, or even scholastics, we would then deduce that the important part of the ceremony of dedication, the one that brings about what everybody is there to do, is the Mass. We could believe that all the other ceremonies, like the anointing with chrism, are really superfluous liturgical padding, done because we are ordered to do them by the rubrics, and because they add solemnity to the rite as a whole, but of no real practical use. In contrast, the bishop reminds us that these are holy rites. They are liturgy, and liturgy, all liturgy, is the product of the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church, is a participation in the liturgy of heaven and hence has a sacramental dimension. When holy water is sprinkled or, even more so, when someone or something is anointed with chrism, then the Holy Spirit is doing something. It is for us to discern what he is doing It is not possible to separate the "essntial" from the "non-essential" because they form an inseparable whole.

When Russians drink a toast, they smash the glass afterwards to indicate that who or what they have toasted is of such importance that the glass should not be used for any inferior purpose. Where God speaks through his word, where the Holy Spirit transforms mere human beings into sons and daughters of God at baptism, where the Father responds to the prayer of the priest and sends the Holy Spirit to transform bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood and the praying congregation into the body of Christ and temple of the Holy Spirit, the Church thinks it appropriate that such a place, together with the chalice and pattern, are so holy that they should not be used for any inferior purpose. Changing uranium into nuclear fuel leaves behind material that remains radioactive for tens of thousands of years. The rite of dedication teaches us that a single Mass can make a building or an altar holy for as long as it exists. Of course, it is often necessary to celebrate the Mass and sacraments in places that cannot be reserved for worship and to use ordinary tables as altars; but it is so easy to underestimate the holiness of the Mass and sacraments if we do not give to those material things most associated with their celebration the kind of respect that human beings have naturally given to holy things throughout history. For this reason, it is better to consecrate the building that is used for Mass and to use it only for liturgical functions. I have a gut feeling that something is wrong when we use a room or a table that has been used for Mass over a period of time for some other purpose. In saying this we recognize that, in practical terms, while the holiness of any Mass can consecrate a building, not every Mass does. There needs to be the intention of the bishop to dedicate the building exclusively for the liturgy for a dedication to take place, and the Mass needs to be celebrated for that purpose..

The question still remains: if a Mass is enough to dedicate a church or an altar, what is accomplished by the sprinkling with holy water, the epiclesis or invocation, and by the anointing with holy chrism?

The first thing that comes to mind is how the order of sprinkling, anointing, followed by the celebration of the Eucharist mirrors the classic order of the sacraments of initiation, of baptism, confirmation and communion. When icons are blessed in the Eastern Orthodox Church, they too are sprinkled with holy water and anointed with chrism Does the consecrated church together with its altar constitute an icon? It is never called an icon, not because it is less than an icon but because it belongs to a different order: it is the context in which God manifests his presence in Christ, while an icon is an instrument of that manifestation. Nevertheless, the consecratory prayer is going to say that the church and altar reflect the mystery of the Church, and it is clear from the whole prayer that we participate in that mystery in church; so it is certainly icon-like. .

On entering the church and after greeting the people, the bishop solemnly blesses water which shall be used, he says, to remind the people of their baptism and a “symbol of the cleansing of these walls and this altar”. There we have the parallel between baptism and the sprinkling of holy water on the altar and walls. These are ‘purified’, cleansed of any harmful influences due to sin and dedicated to an unspecified Christian use. Sprinkling them with holy water is a way to lay claim to them on behalf of the Church. From now on they are to be used in the continual passing through death to life that is the very pulse beat and rythm of the body of Christ. After sprinkling, the meaning of this act is summed up as follows:

May God, the Father of mercies, dwell in this house of prayer. May the grace of the Holy Spirit cleanse us, for we are the temple of his presence. Amen

After the readings, the homily, and the Creed, the Litany of the Saints is said in place of the General Intercession. The next main part is the Prayer of Dedication which contains the epiclesis. This is a place in the liturgy where, normally, the purpose of the rite is expressed succinctly. In the epiclesis, what is the Church asking the Father in Jesus’ name? In the solemn prayer of dedication, the bishop first states the purpose of the occasion:

Father in heaven, source of holiness and true purpose (…) today we come before you, to dedicate to your lasting service this house of prayer, this temple of worship, this home in which we are nourished by your word and your sacraments.

It then says that this house reflects the mystery which is the Church. The Church is fruitful and holy by the blood of Christ. It is the Bride made radiant by his glory, a Virgin splendid in the wholeness of her faith, and Mother blessed by the power of the Holy Spirit. We have seen that these are titles given to Mary as a person in her relationship with Jesus. The Church too has thee titles The prayer continues to use metaphor to describe the Church. It is a vineyard with branches all over the world and reaching up to heaven. The Church is a temple, God’s dwelling place on earth, made up of living stones, with Jesus Christ as the corner stone. The Church is a city set on a mountain, a beacon to the whole world, bright with the glory of the Lamb.

Now we come to the invocation (epiclesis) proper:

Lord, send our Spirit from heaven to make this church an ever-holy place, and this altar a ready table for the sacrifice of Christ.

It continues by asking that the sacraments celebrated here will be efficacious, that baptism will overwhelm sin and that the people will truly die to sin, that the people gathered round the altar may celebrate the memorial of the Paschal Lamb and be fed at the table of Christ’s word and Christ’s body. Then the perspective changes; and the prayer goes on to ask that what happens here will have a world-wide effect. It asks that the Eucharist, which is the prayer of the Church, “resound through heaven and earth as a plea for the world’s salvation”. It asks that through it the poor may find justice and the oppressed liberation. It then goes on to ask:

From here may the whole world clothed in the dignity of children of God, enter with gladness your city of peace.

This is a dimension of the Christian life little taught at an ordinary parish level. It asks that as we approach the heavenly Jerusalem with the blood of Christ and pass through the veil which is the body of Christ into the presence of the Father, we may take the whole human race with us. We are Catholics, not just for ourselves but for the salvation of the world, and the unity of the Church is an effective sign of the unity of the human race in the eyes of God The prayer ends with a doxology and the people answer, “Amen”.

Next comes the anointing of the altar and the walls of the church with chrism. Symeon of Thessalonica wrote of the anointing of the altar:

The Altar is perfected through Holy Chrism. A prophetic hymn is chanted, signifying the incoming presence and praise of God. “The Lord comes,” says the Bishop, referring to Christ’s First and Second Coming, and the continuous presence of the Spirit with us. …Since the Chrism is poured out in the name of Christ our God, and the Table represents Him Who was buried therein, it is anointed with Chrism; and it becomes Holy Chrism for it receives the Grace of the Spirit. And for this reason, as we have said, the “Alleluia” is chanted, for God dwells in there; and the Altar becomes the workshop of the Gifts of the Spirit. For on it the Awesome and Mystical Sacraments are celebrated: the ordination of priests, the most Holy Chrism, and the Gospel is placed thereon, and beneath it the Holy Relics of the Martyrs are deposited. Thus this table becomes an Altar of Christ, and a Throne of Glory, and the dwelling-place of God, and the Tomb and Grave of Christ and a place of Rest.

The bishop in our Roman Rite introduces the anointing with the following words:

We now anoint this altar and this building. May God in his power make them holy, visible signs of the mystery of Christ and his Church.

Clearly, these words indicate that it is God who makes the church and altar is never referred to in Tradition as an icon because it is an instrument used by the Church at a higher level of Christian Reality than icons. Icons depict some aspect of the Christian Mystery, and the Holy Spirit brings the person of faith into contact with what is depicted. On the other hand, the altar is the place where what is depicted in icons in present for real. A crucifix depicts Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, while on the altar is the sacrifice itself. The Blessed Virgin, angels and saints are depicted in icons, but they are present at every Mass, joining with us in crying “Holy, holy, holy.”. Everything that has a visual dimension can be depicted in icons, but the altar is the throne of Him who cannot be depicted. For this reason our attention is not directed towards the structure of the altar, but to its surface and the empty space above it. For this reason the empty space should not be cluttered up with unnecessary books or furniture - it is not a bench to put things on - so that priest and people will have a clear, uninterrupted view of the paten and chalice which are central to the whole action of the Mass.

This cannot happen without the Holy Spirit. As the anointing with chrism is done in silence, we must go to the epiclesis of the consecration of chrism on Maundy Thursday to look further into the significance of the anointing.. .

Only in the second consecratory prayer over the chrism is there any mention of the intended effect of anointing places and things. It asks:May the splendour of holiness shine on the world from every place and thing signed with this oil.

The “splendour of holiness” is nothing less than the effect on people and things when God makes his presence felt. When the walls and altar are anointed, the bishop in the name of Christ and the Church is asking the Father to send the Spirit on them so that the church may become a place of contact between God and the world. The “splendour of holiness” may shine from the church building as a reflection of the “glory of the Lamb” which shines from the Church made up of living stones, so that the building will become a true symbol of the living Church.

“The nations will walk by its light. And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it” This can only happen if God takes the initiative; but the bishop anoints them with the confidence that the Father will answer this prayer positively. The church and the altar have become a place of meeting with Christ where we contact him, because he takes the initiative, using this sacred space as his instrument through the power of the Spirit. We enter into the splendour of holiness when we enter a church, and the altar becomes the central point of focus when we celebrate. It is a challenge to the architect and to those who are responsible for the lay-out of the church building, as well as those who organise and celebrate the liturgy, to help people realize the holiness of this place of meeting between God and his people..

The General Instructions from the Roman Missal have more to say about a church.. There are other focal points in a church, though they all direct our attention eventually to the altar. The first is the ambo which is the desk from which the word of God is proclaimed. The sacredness of this proclamation recalls God’s proclamation of the Law on Mount Sinai and God speaking to Isaiah from his throne in heaven. When the reader says, at the end of the reading, “The word of God”, he is making an enormous claim, the impact of which is normally lost, because it is dismissed as mere ritual. He is saying that GOD is speaking,, as really and as immediately as in any theophany of the Old Testament. When reading the word of God, the reader has lent his voice to Christ who is speaking “whenever the word of God is read in church”. To underline this fact, in the General Instructions for the Roman Missal (272) it lays down that the ambo like the altar, should be permanent and fixed to the ground; it must not be used for any other purpose, except for responsorial psalms and the Prayers of the Faithful who are praying in Christ’s name. The priest is not to read the notices, the monitor is not to makes his admonition, nor the choirmaster direct the choir from the same ambo that is used for the word of God. This ambo must be where everybody can see and hear. Evidently, everything must be done not to give the impression those who read are only fulfilling a ritual, or only reading a not very interesting text, simply because it is written down. Reading the word of God is a ministry and should be reserved to those who have been designated and who know what they are doing and why they are doing it and are prepared spiritually for the task.

Another focal point where God and human beings meet is the baptismal font. The rubrics say:

The baptistery is an area where the baptismal font flows or has been placed. It should be reserved for the sacrament of baptism, and should be a worthy place for Christians to be reborn in water and the Holy Spirit. It may be situated in a chapel inside or outside the church, or in some other part of the church easily seen by the faithful; it should be large enough to accommodate a good number of people. After the Easter season, the Easter candle should be given a place of honour in the baptistery, so that when it is lighted for the celebration of baptism, the candles of the newly baptised may easily be lighted from it.

There is also the confessional, but, apart from taking note that there should be one, there are no details except that it should be adequate and according to the law.

Let us now summarize what the liturgy tells about the church building. Firstly, the true temple, altar, priest and sacrifice is Christ, and, by extension, his body the Church. The true Church is the community which we enter by baptism and which is formed into the body of Christ by the Eucharist. The church building is an icon of the Church. It gets its name for this reason. It gets its sacred character from the fact that the word of God is heard there and the sacraments celebrated there, and, most especially, because it is the place where the Church gathers for the Eucharist. By using it we participate in the mystery it represents. However, this dignity does not belong to the building permanently until it is consecrated by the bishop who blesses it with water and anoints it with oil, an analogy with baptism and confirmation. When something is blessed with holy water, it is the Church and Christ through the Church laying claim to whatever is blessed, without necessarily determining its use. The blessing with water is an invitation to those taking part to renew their baptism and is used to purify the building from any contamination by sin. This blessing is also used when the church is merely blest. It is the anointing that gives the church its permanent function. Consecration of a church is not a sacrament because it is of ecclesiastical origin, but it is sacramental, in that the gesture of anointing expresses both the Church’s petition and God’s response. The bishop consecrates, but it is the Holy Spirit who makes the church holy, claiming it on behalf of the risen Jesus who is Lord of heaven and earth. Anyone who enters it with the right dispositions shares in the mystery of the Church. Moreover, the building speaks to the world of God by its very presence in the world. Of course, if it looks like a factory or a space ship, it probably won’t be able to fulfil that function, but that is its function.

Within the church, the altar is the only piece of furniture blessed with water and anointed with oil. It should be fixed and in a prominent place, so that all eyes are drawn to it. In a church of the Latin Rite, it is the only object that is so blessed and anointed. On its surface, the Holy Trinity is manifested in the consecration of the bread and wine, the Church is identified with Christ in his sacrifice to the Father, and is taken up through Christ’s death, resurrection and ascension into the presence of the Father, passing through the veil of the Holy of Holies by communion in Christ’s body. It is from the altar that the people are sent forth to be witnesses to “what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands."

THE ALTAR

"We think: we go to the temple, we come together as brothers - that is good, it's beautiful - but the centre is where God is. And we adore God. More important is the adoration: the whole community unites to see the altar where the sacrifice is celebrated and adored." (Pope Francis)

If you enter a modern church like Worth Abbey, Clifton Cathedral or Leyland Parish Church, you will be struck by the central position of the altar and how the eyes of those who enter are automatically drawn towards it. However, there is no real sanctuary as in the more traditional layout: it is more like a stage. The Eucharist is the centre of Church, so the altar is placed at the centre of the assembly. In words taken from the rite of the Consecration of an Altar, we are “gathered round His altar in love”.

The altar is prominent because it is the holiest place in the church, indeed, as an Orthodox writer put it, "(It) is the holiest place that can be found on earth. The Majesty of God descends upon the Altar, when the Bloodless Sacrifice of Christ is performed on it.” Another Orthodox writer says:

The altar is prominent because it is the holiest place in the church, indeed, as an Orthodox writer put it, "(It) is the holiest place that can be found on earth. The Majesty of God descends upon the Altar, when the Bloodless Sacrifice of Christ is performed on it.” Another Orthodox writer says:

The central and most important part of the Church, which is the Holy Altar, is blessed and sanctified by the ritual of the Consecration. According to Nikolaos Cabasilas: “the purpose of the Holy Mysteries is this: to prepare us for the true life…the altar is the starting point for every rite, whether it be to communicate or to receive Chrism, as well as to administer Holy Orders and the perfections of Baptism…(the altar is) the foundation or root of the Sacraments…”

Symeon of Thessalonica emphasizes the same point:

Just as a bishop or priest is needed to celebrate the Divine Liturgy, and a bishop to celebrate Holy Orders and the Sacrament of Chrism, in like manner these rites have need of an altar for the altar is the church; for it is on the altar that the Liturgy and Holy Orders and the Chrism take place… Through the altar the church is made holy; for without an altar there can be no church, but only a House of Prayer… [without an altar]it is not the Tabernacle of God’s glory, nor His dwelling place…nor can the divine gifts be offered on its Table…

(Announcing the Consecration of the

Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church

Stamford, Connecticut

Sunday November 2, 2008)

Sir Ninian Comper, the great Anglo-Catholic architect, summarizes Catholic tradition when he says:

[A church] is a building which enshrines the altar of Him who dwelleth not in temples made with hands and who yet has made there His Covenanted Presence on earth. It is the centre of Worship in every community of men who recognize Christ as the Pantokrator, the Almighty, the Ruler and Creator of all things: at its altar is pleaded the daily Sacrifice in complete union with the Church Triumphant in Heaven, of which He is the one and only Head, the High Priest for ever after the order of Melchisedech.

Of the church building he writes:

A church built with hands ...is the outward expression here on earth of that spiritual Church built of living stones, the Bride of Christ, Urbs beata Jerusalem, which stretches back to the foundation of the world and onwards to all eternity. With her Lord she lays claim to the whole of His Creation ...And so the temple here on earth, in different lands and in different shapes, in the East and in the West, has developed or added to itself fresh forms of beauty and, though it has suffered from iconoclasts and destroyers both within and without, ...it has never broken with the past, it has never renounced its claims to continue.

In the Assyrian Rite which is in Aramaic and has its roots in apostolic times, the priest says:

Before the glorious throne of Thy majesty, my Lord, and the high and exalted seat of Thy honour and the awesome judgement seat of the power of Thy love, and the absolving altar which Thy will has established and the place where Thy honour dwells, we, Thy people and the sheep of Thy pasture, with thousands of Cherubim which sing halleluiahs to Thee, ten thousand Seraphim and Archangels which hallow Thee, do kneel and worship and confess and glorify Thee at all times, O Lord of all, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, for ever. Amen.

At communion the choir sings,

The cherubim and seraphim and archangels in fear and trembling stand before the altar, and gaze at the priest breaking and dividing the body of Christ, for the pardon of trespasses.

In the Byzantine Rite the whole sanctuary behind the ikonostasis can be called the “altar” and is considered an extension of it, and the altar itself is also called “holy table” and “throne”, and its meaning cannot be understood without reference to the Old Testament. The word “sacrifice” in Hebrew comes from a verb that means “to approach”. Sacrifice was a combined offering by human beings and acceptance by God. It was the context in which God’s Presence among men was accomplished and continued. This was never more so than in the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem temple where the high priest went in every year on the Day of Atonement to offer sacrifice by pouring blood on the tip of temple mount that came up through the floor. God’s Presence that was manifested in the acceptance by God of the sacrifice of Atonement once a year was a very special Presence indeed. God’s acceptance of the Atonement sacrifice implied a permanent Presence, even though the sacrifice took place only once a year; and it was a Presence among the people that gave substance to the Covenant between God and the Jews. He was present because he was their God and they were his People; and the Holy of Holies was where the two met. The Holy of Holies was the holiest place in the world, where sacrifice was transformed into Presence and the world was saved from chaos. God was enthroned in the empty space over the Ark of the Covenant in the first temple, and above the bare top of the temple mount after the temple’s re-building. The Romans discovered to their surprise that the Holy of Holies was totally empty, but the Jews knew that this emptiness was full of God because of the sacrifice that was celebrated there once a year. The rock was also the exact spot, according to Jewish belief, where Abraham attempted to sacrifice Isaac and where he offered the sacrifice “which the Lord had provided” Covenanted Presence and the sacrifice of atonement were linked together in temple theology.

There are obvious parallels between the Holy of Holies and the Christian altar. In the Byzantine Liturgy, the biblical roots of our understanding of the altar are very clear. It is the altar of sacrifice, representing Calvary; it is the Throne or Mercy Seat upon which the blood of Christ is sprinkled for our Atonement and from which God, in his Mercy, showers his grace on humankind, and this is the reason why the deacon calls on the people to ask God’s mercy so often during the celebration of the Byzantine Liturgy. The altar is Christ's tomb because from it comes the risen Christ to save us; it is the holy table of the Messianic feast, the marriage feast of the Lamb; and it represents and projects onto earth the altar in heaven. It is the place where heaven and earth are joined, and where the Parousia or Second Coming is anticipated. As God’s throne or mercy-seat, it is not orientated in any direction. On the contrary, everything and everybody are orientated towards it; and it is reaching up to heaven. In a word, the altar is the “liturgical East” to which both priest and people direct their gaze when they celebrate the Eucharist.

Let us think, for a moment, about the great altar of the Jerusalem temple, just outside the Holy of Holies. This too can help us understand the role of the Christian altar. The altar that was placed before the inner sanctuary did not look like the altars we are used to. It was very high, and the priests reached the top by climbing a ramp; and it normally had a fire burning on top of it which would consume the offerings. The Fathers of the Church, especially St John Chrysostom, were not slow in identifying the Holy Spirit as the Fire that comes down on the altar to consume and transform the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. St John Chrysostom draws a parallel between what happened when Elijah invoked the Lord who sent down fire from heaven to consume the animal sacrifices on the mountain, and the priest who invokes the Lord who sends the Spirit on the bread and wine, as all heaven keeps reverent silence. St Symeon the New Theologian and St Seraphim of Zarov both saw the uncreated light of God descend on the gifts during the Eucharistic Prayer, The Father sends his Spirit who transforms the gifts and also ourselves to the degree that we allow him, and sustains by his divine activity the existence of the gifts as sacraments.

It can be asked why, if the altar is not orientated in any particular direction except, perhaps, upwards, being the meeting place between the Church and the Tri-une God, it has been traditionally placed at the eastern end of a church building, so that all who use it are facing East. The answer is liturgical symbolism. The eastward position links these three holy places together: the altars in the Jerusalem temple and the altar in the heavenly temple are linked with the visible altar on which Mass is celebrated. However, it remains true that the links are there, even when the eastern position has been abandoned in favour of the modern lay-out. For this reason, the altar remains the “liturgical east” and the focal point of the celebration, whichever way the priest is facing. Whether the priest has his back to the people or is facing the people, he, like the people, is facing the altar where the active Presence of the Blessed Trinity becomes one with the Church in bringing about the Eucharistic Sacrifice, linking the earthly altar with the heavenly altar (Roman Canon) and with all other altars on earth across time and space. The Roman Canon pictures the consecration of the elements, not as Jesus coming down on the altar so much as the whole celebration being lifted up to the altar in heaven where we join the angels, the apostles and the martyrs.in offering praise to God. Hence, the attention is upwards towards heaven, and the altar is the point of contact between heaven and earth. It is called many things. The altar is "the glorious throne", "the high and exalted seat" of God's Presence, "the awesome judgement seat of the power" of God's love, "the absolving altar" where God's honour dwells (Assyrian Rite). The altar is heaven's gate through which the Apostle John passed on Patmos to join in the Liturgy of heaven, and through which we pass into God's presence every time we participate in the Mass.

Like in the Holy of Holies, it is not the furniture in itself that is the holiest point in the church, but the surface and the space above it. The altar’s true holiness arises from what is performed on it. As altar, it is sanctified by the sacrifice that is offered on it; as throne it is sanctified by the divine, merciful Presence that sits on it and presents us with the sacrifice that the “Lord will provide” ; as table it is sanctified by the food that is laid on it. The Altar is not only the true centre of the church building, indeed, without which it is not a church, but is where the new covenant becomes a reality. The altar is the true centre of the human race which is transformed by the Mass that is celebrated on it; and is the centre of the universe which is destined to pass through the death and resurrection of Christ into the life of the Blessed Trinity. For this reason, in the modern Roman Rite, the altar is kept free of clutter, so that there is unimpeded view of the altar surface where the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. As the altar is a projection on earth of the altar in heaven, the table by which we partake in the Wedding Feast of the Lamb, while we look on the altar, we internally focus on heaven with the angels and the saints, not on one another; and, in being united to Christ in heaven by the power of the Holy Spirit, our unity with one another and our unity with all across time and space who have celebrated in the past, are celebrating now, or will celebrate in the future, is forged into one organic whole, the Catholic Church. It is a unity forged in Christ who is in heaven, not a unity constructed out of our feelings of togetherness on earth..

Statues and pictures of saints are not to be placed over the altar (Ded. Of Altar. Rubric 10.) Neither are relics to be cemented into the surface of the altar, nor may relics be placed on it for the devotion of the people (No. 10 & 11): it is holier than the holiest relic, holier than any icon, because the Reality that all icons depict is celebrated on it. However, both in East and West, a crucifix is closely associated with the altar, either on it or near it. It is often a processional cross. It is not the centre of attention because the altar is that. Nevertheless it has an important role. There are two ways by which the Church relates to Christ’s death on the cross which come together in the Mass: firstly there is its historical memory, a memory that is contained in the Gospels and passed down from proclamation to proclamation, generation to generation, and which the Holy Spirit makes for us the fullest and most complete revelation of God in the flesh. Secondly, we are brought into the death and resurrection of Christ by sacramental participation in the sacrifice of the Mass. The crucifix is in a prominent place because it demonstrates that what is happening on the altar is one with what the Church remembers. However, it is often placed to one side so as not to impede the sight of the sacred gifts by priest and people. The other icon associated with the altar is the Gospel book which is carried in procession and is placed on the altar from which it is taken from there to be proclaimed at the correct moment.

The altar is treated very differently in the Orthodox East. In our Victorian gothic monastic church the altar is under the tower and the presiding priest faces the people; while in an Eastern rite church, the presiding priest faces East, and the altar is separated from the people by an "ikonostasis". However, at both Masses the concelebrating priests face the altar, looking, not towards the East wall or the crucifix or the people, but at what is happening in that sacred space on the surface of the altar. In the West, We clear away whatever impedes the view of its surface, thus directing attention towards the main action; while in the East they honour the altar by enclosing it in a sanctuary in which only those who are officiating may enter and, by so doing emphasising the holiness of what is taking place there: two ways of honouring the holiness of the altar and what goes on there, and this reflects our different cultures.

We can now summarise what we know about the altar:

1) The altar is the focal point of the Eucharistic celebration. Whether the priest and people are all facing east, or the priest is facing the people, both priest and people are focused on the altar, or should be. If priest and people are conscious of what is happening on the altar, nothing less than a theophany of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, they will not waste time looking at each other, but will be bowed down in humility and love, offering to God, “an acceptable worship with reverence and awe; for indeed our God is a consuming fire.” (Hb. 12, 28f).

It is a common abuse and a misunderstanding of the whole meaning of the post-Vatican II liturgy if "Mass facing the people" is interpreted to mean "Mass in which the main focus of attention of the priest is the people, and the main focus of attention of the people is the priest". The focal point of the Eucharist, whatever way the altar is facing, is the altar itself; and the attention of the whole community, priests, altar servers and people, is directed towards it and what is happening on it..

I know that some priests treat the altar like a demonstration desk and keep their eyes on the people all the time, even mistakenly treating the little elevation during the doxology at the end of the Eucharistic Prayer as though they are showing the gifts to the people. Others act as though the Mass is like a television show, with the priest as the main attraction.

The oldest and simplest rubric for celebrating the Liturgy as well as for living the Christian life is that of St John the Baptist who said of Christ, "He must increase, and I must decrease." Metropolitan Anthony Bloom used to to have a saying which he attributed to St John Chrysostom, "For Christ to appear, the priest must disappear." The two-fold role of the priest is to act in persona Christi and to introduce the people, through Christ, into the presence of the Blessed Trinity. A liturgy that fails to introduce the people though Christ into God's active presence and re-focuses the action onto either the priest or the people is simply failing as Liturgy.

I do not blame the post-Vatican II for much of the abuse. It existed before, but people didn't notice it. Liturgical egoism abounded just as much before Vatican II: it just wasn't noticed and, of course, took different forms: proud prelates and prima donas in lace. Indeed, too much interest in lace and incense was looked on with suspicion, and seminarians believed they best served their vocation by concentrating on pastoral studies and football. Thus, when the changes came, many priests and sisters approached the new Mass with little litugical formation; and this has showed. They simply do not understand liturgy, and it can be blamed on their seminary training, not on the position of the altar or on the liturgy itself.

It is a common abuse and a misunderstanding of the whole meaning of the post-Vatican II liturgy if "Mass facing the people" is interpreted to mean "Mass in which the main focus of attention of the priest is the people, and the main focus of attention of the people is the priest". The focal point of the Eucharist, whatever way the altar is facing, is the altar itself; and the attention of the whole community, priests, altar servers and people, is directed towards it and what is happening on it..

I know that some priests treat the altar like a demonstration desk and keep their eyes on the people all the time, even mistakenly treating the little elevation during the doxology at the end of the Eucharistic Prayer as though they are showing the gifts to the people. Others act as though the Mass is like a television show, with the priest as the main attraction.

The oldest and simplest rubric for celebrating the Liturgy as well as for living the Christian life is that of St John the Baptist who said of Christ, "He must increase, and I must decrease." Metropolitan Anthony Bloom used to to have a saying which he attributed to St John Chrysostom, "For Christ to appear, the priest must disappear." The two-fold role of the priest is to act in persona Christi and to introduce the people, through Christ, into the presence of the Blessed Trinity. A liturgy that fails to introduce the people though Christ into God's active presence and re-focuses the action onto either the priest or the people is simply failing as Liturgy.

I do not blame the post-Vatican II for much of the abuse. It existed before, but people didn't notice it. Liturgical egoism abounded just as much before Vatican II: it just wasn't noticed and, of course, took different forms: proud prelates and prima donas in lace. Indeed, too much interest in lace and incense was looked on with suspicion, and seminarians believed they best served their vocation by concentrating on pastoral studies and football. Thus, when the changes came, many priests and sisters approached the new Mass with little litugical formation; and this has showed. They simply do not understand liturgy, and it can be blamed on their seminary training, not on the position of the altar or on the liturgy itself.

It is laid down in the rubrics (DA 7) that in new churches there should only be one altar. “It should be placed in a central position which draws the attention of the whole congregation” (CA 8) "The whole congregation" includes the priest. In a consecrated church it should be fixed to the floor and should normally be made of stone, unless the bishops decide otherwise (CA 9). The altar should be free standing “so that the priest can easily walk around it and celebrate Mass facing the people” (CA 8). (The Roman Missal General Instruction, No. 262). “The altar is dedicated to the one God by its very nature. (About the Church’s custom of dedicating altars to saints) “St Augustine expresses it well, ‘It is not to any of the martyrs, but to the God of the martyrs, though in memory of the martyrs, that we raise our altars.” (Contra Faustum XX, 21. PL 42, 3884). No statues or pictures of the saints should be placed over an altar in new churches, nor should relics of saints be placed on the altar for the veneration of the faithful (CA10). It is fitting that the custom of the Roman liturgy to celebrate Mass over the relics be retained, but these relics must be authentic and not placed either over the altar or set into the table slab, but in a special place under the altar. (CA11)

The Blessed Sacrament is preferably reserved in a chapel to some extent apart from the main body of the church, and another altar may be built there and used during weekdays when there are few people attending Mass. You may be somewhat surprised that it is recommended that the Blessed Sacrament should be in a chapel apart. Surely one of the most wonderful developments in the West has been adoration of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. It has been a main factor in the sanctity of many saints, and a sense of Presence associated with the tabernacle has been a cause of many conversions. Why then do liturgists say it should be in a chapel apart? Is it a move in a Protestant direction?

The problem is that we have such a lively devotion to Christ in the sacramental host that it tends to take our attention away from other important ways in which God is present with his people. For instance, next to the Blessed Sacrament, icons tend to lose their sacred function, which is a pity. Even more important is the active presence of all three Persons of the Blessed Trinity in the Mass, and not just Jesus in the host. The active presence of the Holy Trinity is expressed at the beginning of the celebration in the words of St Paul, “The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God (the Father), and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit, be with you. all.”. It is also expressed in the Doxology, “Through Him (Christ), with Him and in Him, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, all honour and glory is Yours, almighty Father, for ever and ever.” As is affirmed in the priest’s greeting in the Byzantine Rite, this participation by mere creatures in the life of the Blessed Trinity is what is meant by “the kingdom of God” When Eastern Christian touch the ground with their foreheads on entering a church during Lent, they are acknowledging the Divine Presence, not in the. Blessed Sacrament, but the Presence focused on the altar as the new Holy of Holies where the Atonement sacrifice is celebrated. Christ’s presence in the Blessed Sacrament as our food is understood as the central means by which we enter into the life of the Trinity. This presence of the Blessed Trinity expresses itself in different ways during the course of the Mass; and, if we wish the faithful to become aware of the nuances of God’s presence, that Christ is the Father’s Word who speaks in the Liturgy of the Word by the power of the Holy Spirit, that the consecration is a prayer on behalf of the Church and in Christ’s Name to the Father, that when we pray the Mass and sing, we do so with Christ in the Spirit, so that the Father is both the Source and Goal of our praise, we need to separate the celebration from the continual presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament which tends to hold the peoples’ attention to the exclusion of everything else. We can either discourage devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, which would be to diminish our own spiritual patrimony; or we can place the tabernacle in a central place, but behind the celebrant who has his back to it; or we can keep the Blessed Sacrament in a chapel apart from the main altar..In our monastery church we suspend the tabernacle or pyx over the altar. We believe it to be the best solution - though it would be impracticable we we needed to store a large quantity of hosts - because it associates the continued eucharistic presence of Christ in the consecrated hosts with the altar, gives that presence a central position, but without being an obstacle to the people appreciating the various shades, degrees and means by which Christ is present with them; and it does not impede the people from seeing what is going on on the altar

In the Old Testament, the people knew that their sacrifices were acceptable to God because they were laid on or poured out on altars that God had himself established. The altar sanctified the offering because God's Presence had decreed his sanctifying Presence in the Covenant to accept the sacrifices. In contrast, the Christian altar is sanctified by what is laid on it, by the body and blood of the the Lord. St Augustine tells us very succinctly, beginning with a quotation from Matthew 23, 17, “The Lord says to the Jews, ‘What is more important, the offering or the altar which sanctifies the offering?’ For the temple and the altar we must understand the Christ himself; for the gold and the offerings, the praises and sacrifices of prayers which we offer through him. It is not the offerings which sanctify Christ, but rather Christ who sanctifies the offerings.” (PL 35, 1329) Christ is the only sacrifice completely worthy of the Father, the only altar capable of sanctifying anything or anybody, and the only temple in which God dwells bodily. The incredible thing is that in the Mass we are doing something that no creature, not even the angels, can do by their own nature, only because of the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church: the glory which we give to God is nothing less than the glory that God is giving to God: we are sharing in the life of the Trinity, but always by entering into the death, resurrection and ascension of Christ; and.the focal point, what some call the "liturgical East", is the place where the Father sends his Son, at his Son's own request, by the power of the Holy Spirit, and the Son offers himself together with us in the unity of the Holy Spirit to the Father: it is the gate of heaven.. This is an anticipation of the "Parousia" or Second Coming. In both East and West, in the ordinary Roman Rite and in its "extraordinary" Latin use, the priests face the altar, as do the people. In the Divine Liturgy for Christmas when I con-celebrated,, there was a priest, the senior one present, who faced West; though not, of course, looking at the people because there was a tabernacle on the altar, and the sanctuary was not visible from the nave. The difference between East and West is that, while in the West we honour the altar by making it as prominent and as easily visible as possible, in the East it is honoured by being hidden in the sanctuary, either by an iconstasis in the Byzantine Rite or by a curtain among the Syrians.

The mystery of the Eucharist is explained by one ancient author:

God came among human beings so that they might meet him. (…) Thine is the kingdom of heaven: ours is thy house. (…) There the priest offers bread in thy name and thou givest thine own body for food to all for food. (..) Thy heavens are too high for us to be able to reach them. But behold thou comest to us in the church, so close. Thy throne rests on fire; who would dare approach? But the Almighty lives and dwells in the bread. Anyone who wishes to may approach and eat. (For the Consecration of a New Church Bickell I. pp 77 – 82)

WHAT WE LEARN FROM THE RITE OF DEDICATION

The church is holy because it houses the gathered Church; and the altar is holy because it is on this table that Mass is celebrated. Let us now look at what the liturgy has to say about the sanctity of a church, using as our chief source the Rite for the Dedication of a Church and the Rite for a Dedication of an Altar. What hits us immediately is the preliminary statement of the bishop to the people at the dedication of a church or an altar. On greeting the people, the bishop should say something like:

Brothers and sisters in Christ, this is a day of rejoicing: we have come to dedicate this church (this altar) by offering the sacrifice of Christ.(for a church) May we open our hearts and minds to receive his word with faith; may our fellowship born in the one font of baptism and sustained at the one table of the Lord, become the one temple of his Spirit, as we gather round his altar in love.

(for an altar) May we respond to these holy rites, receive God’s word with faith, share at the Lord’s table with joy, and raise up our hearts in hope.

We belong to the New Covenant in which all religious institutions of the Old Testament have been replaced by people. Christ is the temple, the priesthood, the only victim and the altar, and has also replaced the Law of Moses as the Way (). The Blessed Virgin Mary is the Ark of the New Covenant; and, when she was by Christ’s side while he was dying on the cross, she embraced both her Son and the whole human race in her love, and thus she came to represent all those down the ages whose synergy with the Holy Spirit would make them one with Christ on the cross: At the foot of the cross she was personally the Church in its relationship to Christ, the New Eve, and Mother of all the living.. As our icon depicts, she is personally what the Church is collectively: she is the Bride of the Lamb.. No longer is God’s dwelling place among the people on earth a building. Since Christ’s Ascension, the temple has been replaced by us who are participants in Christ; we are his body, the Church, in whom God dwells bodily, reconciling the world to himself. By participating in the Eucharistic fellowship we become “the one temple of his Spirit”. In the Old Testament, the covenanted presence of God depended on the temple and the fulfilment of the purification ritual on the Day of the Atonement; and the altar sanctified the offering so that it could be offered on no other altar; and hence the crisis when the temple was destroyed. In New Testament times, in contrast, it is the presence of God’s People that sanctifies the church; and it is the offering by Christ of himself that sanctifies our offering and the altar on which it is placed.

If we were neo-scholastics, or even scholastics, we would then deduce that the important part of the ceremony of dedication, the one that brings about what everybody is there to do, is the Mass. We could believe that all the other ceremonies, like the anointing with chrism, are really superfluous liturgical padding, done because we are ordered to do them by the rubrics, and because they add solemnity to the rite as a whole, but of no real practical use. In contrast, the bishop reminds us that these are holy rites. They are liturgy, and liturgy, all liturgy, is the product of the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church, is a participation in the liturgy of heaven and hence has a sacramental dimension. When holy water is sprinkled or, even more so, when someone or something is anointed with chrism, then the Holy Spirit is doing something. It is for us to discern what he is doing It is not possible to separate the "essntial" from the "non-essential" because they form an inseparable whole.

When Russians drink a toast, they smash the glass afterwards to indicate that who or what they have toasted is of such importance that the glass should not be used for any inferior purpose. Where God speaks through his word, where the Holy Spirit transforms mere human beings into sons and daughters of God at baptism, where the Father responds to the prayer of the priest and sends the Holy Spirit to transform bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood and the praying congregation into the body of Christ and temple of the Holy Spirit, the Church thinks it appropriate that such a place, together with the chalice and pattern, are so holy that they should not be used for any inferior purpose. Changing uranium into nuclear fuel leaves behind material that remains radioactive for tens of thousands of years. The rite of dedication teaches us that a single Mass can make a building or an altar holy for as long as it exists. Of course, it is often necessary to celebrate the Mass and sacraments in places that cannot be reserved for worship and to use ordinary tables as altars; but it is so easy to underestimate the holiness of the Mass and sacraments if we do not give to those material things most associated with their celebration the kind of respect that human beings have naturally given to holy things throughout history. For this reason, it is better to consecrate the building that is used for Mass and to use it only for liturgical functions. I have a gut feeling that something is wrong when we use a room or a table that has been used for Mass over a period of time for some other purpose. In saying this we recognize that, in practical terms, while the holiness of any Mass can consecrate a building, not every Mass does. There needs to be the intention of the bishop to dedicate the building exclusively for the liturgy for a dedication to take place, and the Mass needs to be celebrated for that purpose..

The question still remains: if a Mass is enough to dedicate a church or an altar, what is accomplished by the sprinkling with holy water, the epiclesis or invocation, and by the anointing with holy chrism?

The first thing that comes to mind is how the order of sprinkling, anointing, followed by the celebration of the Eucharist mirrors the classic order of the sacraments of initiation, of baptism, confirmation and communion. When icons are blessed in the Eastern Orthodox Church, they too are sprinkled with holy water and anointed with chrism Does the consecrated church together with its altar constitute an icon? It is never called an icon, not because it is less than an icon but because it belongs to a different order: it is the context in which God manifests his presence in Christ, while an icon is an instrument of that manifestation. Nevertheless, the consecratory prayer is going to say that the church and altar reflect the mystery of the Church, and it is clear from the whole prayer that we participate in that mystery in church; so it is certainly icon-like. .

On entering the church and after greeting the people, the bishop solemnly blesses water which shall be used, he says, to remind the people of their baptism and a “symbol of the cleansing of these walls and this altar”. There we have the parallel between baptism and the sprinkling of holy water on the altar and walls. These are ‘purified’, cleansed of any harmful influences due to sin and dedicated to an unspecified Christian use. Sprinkling them with holy water is a way to lay claim to them on behalf of the Church. From now on they are to be used in the continual passing through death to life that is the very pulse beat and rythm of the body of Christ. After sprinkling, the meaning of this act is summed up as follows:

May God, the Father of mercies, dwell in this house of prayer. May the grace of the Holy Spirit cleanse us, for we are the temple of his presence. Amen

After the readings, the homily, and the Creed, the Litany of the Saints is said in place of the General Intercession. The next main part is the Prayer of Dedication which contains the epiclesis. This is a place in the liturgy where, normally, the purpose of the rite is expressed succinctly. In the epiclesis, what is the Church asking the Father in Jesus’ name? In the solemn prayer of dedication, the bishop first states the purpose of the occasion:

Father in heaven, source of holiness and true purpose (…) today we come before you, to dedicate to your lasting service this house of prayer, this temple of worship, this home in which we are nourished by your word and your sacraments.

It then says that this house reflects the mystery which is the Church. The Church is fruitful and holy by the blood of Christ. It is the Bride made radiant by his glory, a Virgin splendid in the wholeness of her faith, and Mother blessed by the power of the Holy Spirit. We have seen that these are titles given to Mary as a person in her relationship with Jesus. The Church too has thee titles The prayer continues to use metaphor to describe the Church. It is a vineyard with branches all over the world and reaching up to heaven. The Church is a temple, God’s dwelling place on earth, made up of living stones, with Jesus Christ as the corner stone. The Church is a city set on a mountain, a beacon to the whole world, bright with the glory of the Lamb.

Now we come to the invocation (epiclesis) proper:

Lord, send our Spirit from heaven to make this church an ever-holy place, and this altar a ready table for the sacrifice of Christ.

It continues by asking that the sacraments celebrated here will be efficacious, that baptism will overwhelm sin and that the people will truly die to sin, that the people gathered round the altar may celebrate the memorial of the Paschal Lamb and be fed at the table of Christ’s word and Christ’s body. Then the perspective changes; and the prayer goes on to ask that what happens here will have a world-wide effect. It asks that the Eucharist, which is the prayer of the Church, “resound through heaven and earth as a plea for the world’s salvation”. It asks that through it the poor may find justice and the oppressed liberation. It then goes on to ask:

From here may the whole world clothed in the dignity of children of God, enter with gladness your city of peace.

This is a dimension of the Christian life little taught at an ordinary parish level. It asks that as we approach the heavenly Jerusalem with the blood of Christ and pass through the veil which is the body of Christ into the presence of the Father, we may take the whole human race with us. We are Catholics, not just for ourselves but for the salvation of the world, and the unity of the Church is an effective sign of the unity of the human race in the eyes of God The prayer ends with a doxology and the people answer, “Amen”.

Next comes the anointing of the altar and the walls of the church with chrism. Symeon of Thessalonica wrote of the anointing of the altar:

The Alter is perfected through Holy Chrism. A prophetic hymn is chanted, signifying the incoming presence and praise of God. “The Lord comes,” says the Bishop, referring to Christ’s First and Second Coming, and the continuous presence of the Spirit with us. …Since the Chrism is poured out in the name of Christ our God, and the Table represents Him Who was buried therein, it is anointed with Chrism; and it becomes Holy Chrism for it receives the Grace of the Spirit. And for this reason, as we have said, the “Alleluia” is chanted, for God dwells in there; and the Altar becomes the workshop of the Gifts of the Spirit. For on it the Awesome and Mystical Sacraments are celebrated: the ordination of priests, the most Holy Chrism, and the Gospel is placed thereon, and beneath it the Holy Relics of the Martyrs are deposited. Thus this table becomes an Altar of Christ, and a Throne of Glory, and the dwelling-place of God, and the Tomb and Grave of Christ and a place of Rest.