SENSUS FIDEI

IN THE LIFE OF THE CHURCH*

(2014)

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter One: The sensus fidei in Scripture and Tradition

1. Biblical teaching

a) Faith as response to the Word of God

b) The personal and ecclesial dimensions of faith

c) The capacity of believers to know and witness to the truth

2. The development of the idea, and its place in the history of the Church

a) Patristic period

b) Medieval period

c) Reformation and post-Reformation period

d) 19th century

e) 20th century

Chapter Two: The sensus fidei fidelis in the personal life of the believer

1. The sensus fidei as an instinct of faith

2. Manifestations of the sensus fidei in the personal life of believers

Chapter Three: The sensus fidei fidelium in the life of the Church

1. The sensus fidei and the development of Christian doctrine and practice

a) Retrospective and prospective aspects of the sensus fidei

b) The contribution of the laity to the sensus fidelium

2. The sensus fidei and the magisterium

a) The magisterium listens to the sensus fidelium

b) The magisterium nurtures, discerns and judges the sensus fidelium

c) Reception

3. The sensus fidei and theology

a) Theologians depend on the sensus fidelium

b) Theologians reflect on the sensus fidelium

4. Ecumenical aspects of the sensus fidei

Chapter Four: How to discern authentic manifestations of the sensus fidei

1. Dispositions needed for authentic participation in the sensus fidei

a) Participation in the life of the Church

b) Listening to the word of God

c) Openness to reason

d) Adherence to the magisterium

e) Holiness – humility, freedom and joy

f) Seeking the edification of the Church

2. Applications

a) The sensus fidei and popular religiosity

b) The sensus fidei and public opinion

c) Ways of consulting the faithful

Conclusion

* PRELIMINARY NOTE

In its quinquennium of 2009-2014, the International Theological Commission studied the nature of sensus fidei and its place in the life of the Church. The work took place in a subcommission presided by Msgr. Paul McPartlan and composed of the following members: Fr. Serge Thomas Bonino, O.P. (Secretary General); Sr. Sara Butler, M.S.B.T.; Rev. Antonio Castellano, S.D.B.; Rev. Adelbert Denaux; Msgr. Tomislav Ivanĉić; Bishop Jan Liesen; Rev. Leonard Santedi Kinkupu, Doctor Thomas Söding, and Msgr. Jerzy Szymik.

The general discussions of this theme were held in numerous meetings of the subcommission and during the Plenary Sessions of the same International Theological Commission held in Rome between 2011 and 2014. The text “Sensus fidei in the Life of the Church” was approved in forma specifica by the majority of members of commission, by a written vote, and was then submitted to its President, Cardinal Gerhard L. Müller, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, who authorized its publication.

Introduction

1. By the gift of the Holy Spirit, ‘the Spirit of truth who comes from the Father’ and bears witness to the Son (Jn 15:26), all of the baptised participate in the prophetic office of Jesus Christ, ‘the faithful and true witness’ (Rev 3:14). They are to bear witness to the Gospel and to the apostolic faith in the Church and in the world. The Holy Spirit anoints them and equips them for that high calling, conferring on them a very personal and intimate knowledge of the faith of the Church. In the first letter of St John, the faithful are told: ‘you have been anointed by the Holy One, and all of you have knowledge’, ‘the anointing that you received from [Christ] abides in you, and so you do not need anyone to teach you’, ‘his anointing teaches you about all things’ (1Jn 2:20, 27).

2. As a result, the faithful have an instinct for the truth of the Gospel, which enables them to recognise and endorse authentic Christian doctrine and practice, and to reject what is false. That supernatural instinct, intrinsically linked to the gift of faith received in the communion of the Church, is called the sensus fidei, and it enables Christians to fulfil their prophetic calling. In his first Angelus address, Pope Francis quoted the words of a humble, elderly woman he once met: ‘If the Lord did not forgive everything, the world would not exist’; and he commented with admiration: ‘that is the wisdom which the Holy Spirit gives’.[1] The woman’s insight is a striking manifestation of the sensus fidei, which, as well as enabling a certain discernment with regard to the things of faith, fosters true wisdom and gives rise, as here, to proclamation of the truth. It is clear, therefore, that the sensus fidei is a vital resource for the new evangelisation to which the Church is strongly committed in our time.[2]

3. As a theological concept, the sensus fidei refers to two realities which are distinct though closely connected, the proper subject of one being the Church, ‘pillar and bulwark of the truth’ (1Tim 3:15),[3] while the subject of the other is the individual believer, who belongs to the Church through the sacraments of initiation, and who, by means of regular celebration of the Eucharist, in particular, participates in her faith and life. On the one hand, the sensus fidei refers to the personal capacity of the believer, within the communion of the Church, to discern the truth of faith. On the other hand, the sensus fidei refers to a communal and ecclesial reality: the instinct of faith of the Church herself, by which she recognises her Lord and proclaims his word. The sensus fidei in this sense is reflected in the convergence of the baptised in a lived adhesion to a doctrine of faith or to an element of Christian praxis. This convergence (consensus) plays a vital role in the Church: the consensus fidelium is a sure criterion for determining whether a particular doctrine or practice belongs to the apostolic faith.[4]In the present document, we use the term, sensus fidei fidelis, to refer to the personal aptitude of the believer to make an accurate discernment in matters of faith, and sensus fidei fidelium to refer to the Church’s own instinct of faith. According to the context, sensus fidei refers to either the former or the latter, and in the latter case the term, sensus fidelium, is also used.

4. The importance of the sensus fidei in the life of the Church was strongly emphasised by the Second Vatican Council. Banishing the caricature of an active hierarchy and a passive laity, and in particular the notion of a strict separation between the teaching Church (Ecclesia docens) and the learning Church (Ecclesia discens), the council taught that all the baptised participate in their own proper way in the three offices of Christ as prophet, priest and king. In particular, it taught that Christ fulfills his prophetic office not only by means of the hierarchy but also via the laity.

5. In the reception and application of the council’s teaching on this topic, however, many questions arise, especially in relation to controversies regarding various doctrinal or moral issues. What exactly is the sensus fidei and how can it be identified? What are the biblical sources for this idea and how does the sensus fidei function in the tradition of the faith? How does the sensus fidei relate to the ecclesiastical magisterium of the pope and the bishops, and to theology?[5] What are the conditions for an authentic exercise of the sensus fidei? Is the sensus fidei something different from the majority opinion of the faithful in a given time or place, and if so how does it differ from the latter? All of these questions require answers if the idea of the sensus fidei is to be understood more fully and used more confidently in the Church today.

6. The purpose of the present text is not to give an exhaustive account of the sensus fidei, but simply to clarify and deepen some important aspects of this vital notion in order to respond to certain issues, particularly regarding how to identify the authentic sensus fidei in situations of controversy, when for example there are tensions between the teaching of the magisterium and views claiming to express the sensus fidei. Accordingly, it will first consider the biblical sources for the idea of the sensus fidei and the way in which this idea has developed and functioned in the history and tradition of the Church (chapter one). The nature of the sensus fidei fidelis will then be considered, together with the manifestations of the latter in the personal life of the believer (chapter two). The document will then reflect on the sensus fidei fidelium, that is, the sensus fidei in its ecclesial form, considering first its role in the development of Christian doctrine and practice, then its relationship to the magisterium and to theology, respectively, and then also its importance for ecumenical dialogue (chapter three). Finally, it will seek to identify dispositions needed for an authentic participation in the sensus fidei - they constitute criteria for a discernment of the authentic sensus fidei - and will reflect on some applications of its findings to the concrete life of the Church (chapter four).

Chapter 1: The sensus fidei in Scripture and Tradition

7. The phrase, sensus fidei, is found neither in the Scriptures nor in the formal teaching of the Church until Vatican II. However, the idea that the Church as a whole is infallible in her belief, since she is the body and bride of Christ (cf. 1Cor 12:27; Eph 4:12; 5:21-32; Rev 21:9), and that all of her members have an anointing that teaches them (cf. 1Jn 2:20, 27), being endowed with the Spirit of truth (cf. Jn 16:13), is everywhere apparent from the very beginnings of Christianity. The present chapter will trace the main lines of the development of this idea, first in Scripture and then in the subsequent history of the Church.

1. Biblical teaching

a) Faith as response to the Word of God

8. Throughout the New Testament, faith is the fundamental and decisive response of human persons to the Gospel. Jesus proclaims the Gospel in order to bring people to faith: ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news’ (Mk 1:15). Paul reminds the early Christians of his apostolic proclamation of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ in order to renew and deepen their faith: ‘Now I would remind you, brothers and sisters, of the good news that I proclaimed to you, which you in turn received, in which also you stand, through which also you are being saved, if you hold firmly to the message that I proclaimed to you - unless you have come to believe in vain’ (1Cor 15:1-2). The understanding of faith in the New Testament is rooted in the Old Testament, and especially in the faith of Abram, who trusted completely in God’s promises (Gen 15:6; cf. Rom 4:11,17). This faith is a free answer to the proclamation of the word of God, and as such it is a gift of the Holy Spirit to be received by those who truly believe (cf. 1Cor 12:3). The ‘obedience of faith’ (Rom 1:5) is the result of God’s grace, who frees human beings and gives them membership in the Church (Gal 5:1,13).

9. The Gospel calls forth faith because it is not simply the conveying of religious information but the proclamation of the word of God, and ‘the power of God for salvation’, which is truly to be received (Rom 1:16-17; cf. Mt 11:15; Lk 7:22 [Is 26:19; 29:18; 35:5-6; 61:1-11]). It is the Gospel of God’s grace (Acts 20:24), the ‘revelation of the mystery’ of God (Rom 16:25), and the ‘word of truth’ (Eph 1:13). The Gospel has a substantial content: the coming of God’s Kingdom, the resurrection and exaltation of the crucified Jesus Christ, the mystery of salvation and glorification by God in the Holy Spirit. The Gospel has a strong subject: Jesus himself, the Word of God, who sends out his apostles and their followers, and it takes the direct form of inspired and authorised proclamation by words and deeds. To receive the Gospel requires a response of the whole person ‘with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength’ (Mk 12:31). This is the response of faith, which is ‘the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen’ (Heb 11:1).

10. ‘“Faith” is both an act of belief or trust and also that which is believed or confessed, fides qua and fides quae, respectively. Both aspects work together inseparably, since trust is adhesion to a message with intelligible content, and confession cannot be reduced to mere lip service, it must come from the heart.’[6] The Old and New Testaments clearly show that the form and content of faith belong together.

b) The personal and ecclesial dimensions of faith

11. The scriptures show that the personal dimension of faith is integrated into the ecclesial dimension; both singular and plural forms of the first person are found: ‘we believe’ (cf. Gal 2:16) and ‘I believe’ (cf. Gal 2:19-20). In his letters, Paul recognises the faith of believers as both a personal and an ecclesial reality. He teaches that everyone who confesses that ‘Jesus is Lord’ is inspired by the Holy Spirit (1Cor 12:3). The Spirit incorporates every believer into the body of Christ and gives him or her a special role in order to build up the Church (cf. 1Cor 12:4-27). In the letter to the Ephesians, confession of the one and only God is connected with the reality of a life of faith in the Church: ‘There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope of your calling, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is above all and through all and in all’ (Eph 4:4-6).

12. In its personal and ecclesial dimensions, faith has the following essential aspects:

i) Faith requires repentance. In the proclamation of the prophets of Israel and of John the Baptist (cf. Mk 1:4), as well as in the preaching of the Good News by Jesus himself (Mk 1:14f.) and in the mission of the Apostles (Acts 2:38-42; 1Thess 1:9f.), repentance means the confession of one’s sins and the beginning of a new life lived within the community of the covenant of God (cf. Rom 12:1f.).

ii) Faith is both expressed in and nourished by prayer and worship (leiturgia). Prayer can take various forms - begging, imploring, praising, thanksgiving - and the confession of faith is a special form of prayer. Liturgical prayer, and pre-eminently the celebration of the Eucharist, has from the very beginning been essential to the life of the Christian community (cf. Acts 2:42). Prayer takes place both in public (cf. 1Cor 14) and in private (cf. Mt 6:5). For Jesus, the Our Father (Mt 6:9-13; Lk 11:1-4) expresses the essence of faith. It is a ‘summary of the whole Gospel’.[7] Significantly, its language is that of ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’.

iii) Faith brings knowledge. The one who believes is able to recognise the truth of God (cf. Phil 3:10f.). Such knowledge springs from reflection on the experience of God, based on revelation and shared in the community of believers. This is the witness of both Old and New Testament Wisdom theology (Ps 111:10; cf. Prov 1:7; 9:10; Mt 11:27; Lk 10:22).

iv) Faith leads to confession (marturia). Inspired by the Holy Spirit, believers know the one in whom they have placed their trust (cf. 2Tim 1:12), and are able to give an account of the hope that is in them (cf. 1Pet 3:15), thanks to the prophetic and apostolic proclamation of the Gospel (cf. Rom 10:9f.). They do that in their own name; but they do it from within the communion of believers.

v) Faith involves confidence. To trust in God means to base one’s whole life on the promise of God. In Heb 11, many Old Testament believers are mentioned as members of a great procession through time and space to God in heaven, guided by Jesus the ‘the pioneer and perfecter of our faith’ (Heb 12:3). Christians are part of this procession, sharing the same hope and conviction (Heb 11:1), and already ‘surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses’ (Heb 12:1).

vi) Faith entails responsibility, and especially charity and service (diakonia). The disciples will be known ‘by their fruits’ (Mt 7:20). The fruits belong essentially to faith, because faith, which comes from listening to the word of God, requires obedience to his will. The faith which justifies (Gal 2:16) is ‘faith working through love’ (Gal 5:6; cf. Jas 2:21-24). Love for one’s brother and sister is in fact the criterion for love of God (1Jn 4:20).

c) The capacity of believers to know and witness to the truth

13. In Jeremiah, a ‘new covenant’ is promised, one which will involve the internalisation of God’s word: ‘I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. No longer shall they teach one another, or say to each other, “Know the Lord”, for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity, and remember their sin no more’ (Jer 31:33-34). The people of God is to be created anew, receiving ‘a new spirit’, so as to be able to recognise the law and to follow it (Ez 11:19-20). This promise is fulfilled in the ministry of Jesus and the life of the Church by the gift of the Holy Spirit. It is especially fulfilled in the celebration of the Eucharist, where the faithful receive the cup that is ‘the new covenant’ in the Lord’s blood (Lk 22:20; 1Cor 11:25; cf. Rom 11:27; Heb 8:6-12; 10:14-17).

14. In his farewell discourse, in the context of the Last Supper, Jesus promised his disciples the ‘Advocate’, the Spirit of truth (Jn 14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7-14). The Spirit will remind them of the words of Jesus (Jn 14:26), enable them to testify to the word of God (Jn 15:26-27), ‘prove the world wrong about sin and righteousness and judgment’ (Jn 16:8), and ‘guide’ the disciples ‘into all the truth’ (Jn 16:13). All of this happens thanks to the gift of the Spirit through the paschal mystery, celebrated in the life of the Christian community, particularly in the Eucharist, until the Lord comes (cf. 1Cor 11:26). The disciples have an inspired sense for the ever-actual truth of God’s word incarnate in Jesus and of its meaning for today (cf. 2Cor 6:2), and that is what drives the people of God, guided by the Holy Spirit, to bear witness to their faith in the Church and in the world.

15. Moses wished that all of the people might be prophets by receiving the spirit of the Lord (Num 11:29). That wish became an eschatological promise through the prophet, Joel, and at Pentecost Peter proclaims the fulfillment of the promise: ‘In the last days it will be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy’ (Acts 2:17; cf. Joel 3:1). The Spirit who was promised (cf. Acts 1:8) is poured out, enabling the faithful to speak ‘about God's deeds of power’ (Acts 2:11).

16. The first description of the community of believers in Jerusalem combines four elements: ‘They devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers’ (Acts 2:42). Devotion to these four elements powerfully manifests apostolic faith. Faith clings to the authentic teaching of the Apostles, which remembers the teaching of Jesus (cf. Lk 1:1-4); it draws believers into fellowship with one another; it is renewed through the encounter with the Lord in the breaking of bread; and it is nourished in prayer.

17. When in the church of Jerusalem a conflict arose between the Hellenists and the Hebrews about the daily distribution, the twelve apostles summoned ‘the whole community of the disciples’ and took a decision that ‘pleased the whole community’. The whole community chose ‘seven men of good standing, full of the Spirit and of wisdom’, and set them before the apostles who then prayed and laid their hands upon them (Acts 6:1-6). When problems arose in the church of Antioch concerning circumcision and the practice of the Torah, the case was submitted to the judgment of the mother church of Jerusalem. The resulting apostolic council was of the greatest importance for the future of the Church. Luke describes the sequence of events carefully. The ‘apostles and the elders met together to consider this matter’ (Acts 15:6). Peter told the story of his being inspired by the Holy Spirit to baptise Cornelius and his house even though they were uncircumcised (Acts 15:7-11). Paul and Barnabas told of their missionary experience in the local church of Antioch (Acts 15:12; cf. 15:1-5). James reflected on those experiences in the light of the Scriptures (Acts 15:13-18), and proposed a decision that favoured the unity of the Church (Acts 15:19-21). ‘Then the apostles and the elders, with the consent of the whole church, decided to choose men from among their members and to send them to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas’ (Acts 15:22). The letter which communicated the decision was received by the community with the joy of faith (Acts 15:23-33). For Luke, these events demonstrated proper ecclesial action, involving both the pastoral service of the apostles and elders and also the participation of the community, qualified to participate by their faith.

18. Writing to the Corinthians, Paul identifies the foolishness of the cross as the wisdom of God (1Cor 1:18-25). Explaining how this paradox is comprehensible, he says: ‘we have the mind of Christ’ (1Cor 2:16; ἡμεῖς δὲ νοῦν Χριστοῦ ἔχομεν; nos autem sensum Christi habemus, in the Vulgate). ‘We’ here refers to the church of Corinth in communion with her Apostle as part of the whole community of believers (1Cor 1:1-2). The capacity to recognise the crucified Messiah as the wisdom of God is given by the Holy Spirit; it is not a privilege of the wise and the scribes (cf. 1Cor 1:20), but is given to the poor, the marginalised, and to those who are ‘foolish’ in the eyes of the world (1Cor 1:26-29). Even so, Paul criticises the Corinthians for being ‘still of the flesh’, still not ready for ‘solid food’ (1Cor 3:1-4). Their faith needs to mature and to find better expression in their words and deeds.

19. In his own ministry, Paul shows respect for, and a desire to deepen, the faith of his communities. In 2Cor 1:24, he describes his mission as an apostle in the following terms: ‘I do not mean to imply that we lord it over your faith; rather, we are workers with you for your joy, because you stand firm in the faith’, and he encourages the Corinthians: ‘Stand firm in your faith’ (1Cor 16:14). To the Thessalonians, he writes a letter ‘to strengthen and encourage you for the sake of your faith’ (1Thess 3:2), and he prays for the faith of other communities likewise (cf. Col 1:9; Eph 1:17-19). The apostle not only works for an increase in the faith of others, he knows his own faith to be strengthened thereby in a sort of dialogue of faith: ‘… that we may be mutually encouraged by each other's faith, both yours and mine’ (Rom 1:17). The faith of the community is a reference point for Paul’s teaching and a focus for his pastoral service, giving rise to a mutually beneficial interchange between him and his communities.

20. In the first letter of John, the apostolic Tradition is mentioned (1Jn 1:1-4), and the readers are reminded of their baptism: ‘You have been anointed by the Holy One, and all of you have knowledge’ (1Jn 2:20). The letter continues: ‘As for you, the anointing that you received from him abides in you, and so you do not need anyone to teach you. But as his anointing teaches you about all things, and is true and is not a lie, and just as it has taught you, abide in him’ (1Jn 2:27).

21. Finally, in the Book of Revelation, John the prophet repeats in all of his letters to the churches (cf. Rev 2-3) the formula: ‘Let anyone who has an ear listen to what the Spirit is saying to the churches’ (Rev 2:7, et al.). The members of the churches are charged to heed the living word of the Spirit, to receive it, and to give glory to God. It is by the obedience of faith, itself a gift of the Spirit, that the faithful are able to recognise the teaching they are receiving truly as the teaching of the same Spirit, and to respond to the instructions they are given.

2. The development of the idea, and its place in the history of the Church

22. The concept of the sensus fidelium began to be elaborated and used in a more systematic way at the time of the Reformation, though the decisive role of the consensus fidelium in the discernment and development of doctrine concerning faith and morals was already recognised in the patristic and medieval periods. What was still needed, however, was more attention to the specific role of the laity in this regard. That issue received attention particularly from the nineteenth century onwards.

a) Patristic period

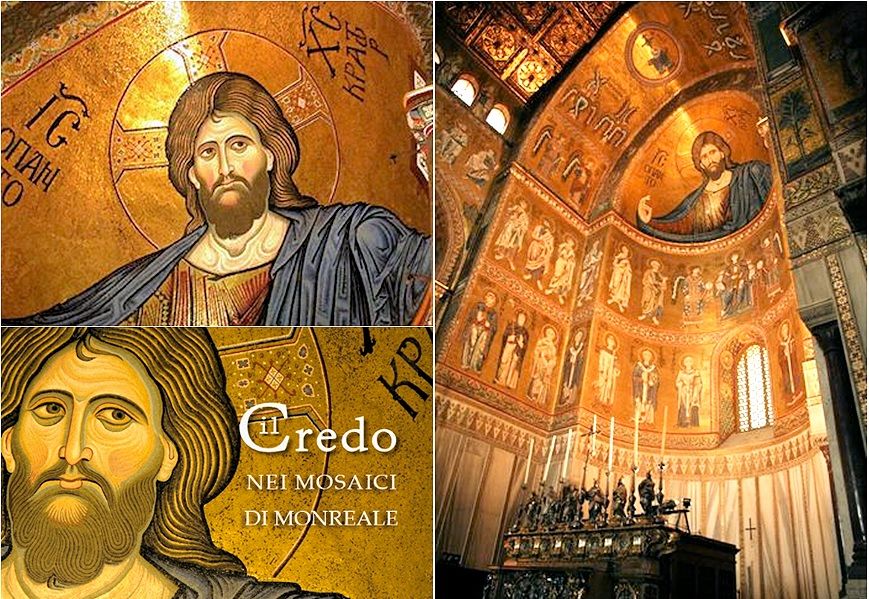

23. The Fathers and theologians of the first few centuries considered the faith of the whole Church to be a sure point of reference for discerning the content of the apostolic Tradition. Their conviction about the solidity and even the infallibility of the discernment of the whole Church on matters of faith and morals was expressed in the context of controversy. They refuted the dangerous novelties introduced by heretics by comparing them with what was held and done in all the churches.[8] For Tertullian (c.160-c.225), the fact that all the churches have substantially the same faith testifies to Christ’s presence and the guidance of the Holy Spirit; those go astray who abandon the faith of the whole Church.[9] For Augustine (354-430), the whole Church, ‘from the bishops to the least of the faithful’, bears witness to the truth.[10] The general consent of Christians functions as a sure norm for determining the apostolic faith: ‘Securus judicat orbis terrarum [the judgement of the whole world is sure]’.[11] John Cassian (c.360-435) held that the universal consent of the faithful is a sufficient argument to confute heretics,[12] and Vincent of Lérins (died c.445) proposed as a norm the faith that was held everywhere, always, and by everyone (quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est).[13]

24. To resolve disputes among the faithful, the Church Fathers appealed not only to common belief but also to the constant tradition of practice. Jerome (c.345-420), for example, found justification for the veneration of relics by pointing to the practice of the bishops and of the faithful,[14] and Epiphanius (c.315-403), in defense of Mary’s perpetual virginity, asked whether anyone had ever dared to utter her name without adding ‘the Virgin’.[15]

25. The testimony of the patristic period chiefly concerns the prophetic witness of the people of God as a whole, something that has a certain objective character. The believing people as a whole cannot err in matters of faith, it was claimed, because they have received an anointing from Christ, the promised Holy Spirit, which equips them to discern the truth. Some Fathers of the Church also reflected on the subjective capacity of Christians animated by faith and indwelt by the Holy Spirit to maintain true doctrine in the Church and to reject error. Augustine, for example, called attention to this when he asserted that Christ ‘the interior Teacher’ enables the laity as well as their pastors not only to receive the truth of revelation but also to approve and transmit it.[16]

26. In the first five centuries, the faith of the Church as a whole proved decisive in determining the canon of Scripture and in defining major doctrines concerning, for example, the divinity of Christ, the perpetual virginity and divine motherhood of Mary, and the veneration and invocation of the saints. In some cases, as Blessed John Henry Newman (1801-90) remarked, the faith of the laity, in particular, played a crucial role. The most striking example was in the famous controversy in the fourth century with the Arians, who were condemned at the Council of Nicaea (325 AD), where the divinity of Jesus Christ was defined. From then until the Council of Constantinople (381 AD), however, there continued to be uncertainty among the bishops. During that period, ‘the divine tradition committed to the infallible Church was proclaimed and maintained far more by the faithful than by the Episcopate’. ‘[T]here was a temporary suspense of the functions of the “Ecclesia docens”. The body of Bishops failed in their confession of the faith. They spoke variously, one against another; there was nothing, after Nicaea, of firm, unvarying, consistent testimony, for nearly sixty years.’[17]

b) Medieval period

27. Newman also commented that ‘in a later age, when the learned Benedictines of Germany [cf. Rabanus Maurus, c.780-856] and France [cf. Ratramnus, died c.870] were perplexed in their enunciation of the doctrine of the Real Presence, Paschasius [c.790 - c.860] was supported by the faithful in his maintenance of it.’[18] Something similar happened with respect to the dogma, defined by Pope Benedict XII in the constitution, Benedictus Deus (1336), regarding the beatific vision, enjoyed already by souls after purgatory and before the day of judgement:[19] ‘the tradition, on which the definition was made, was manifested in the consensus fidelium, with a luminousness which the succession of Bishops, though many of them were “Sancti Patres ab ipsis Apostolorum temporibus”, did not furnish’. ‘[M]ost considerable deference was paid to the “sensus fidelium”; their opinion and advice indeed was not asked, but their testimony was taken, their feelings consulted, their impatience, I had almost said, feared.’[20] The continuing development, among the faithful, of belief in, and devotion to, the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, in spite of opposition to the doctrine by certain theologians, is another major example of the role played in the Middle Ages by the sensus fidelium.

28. The Scholastic doctors acknowledged that the Church, the congregatio fidelium, cannot err in matters of faith because she is taught by God, united with Christ her Head, and indwelt by the Holy Spirit. Thomas Aquinas, for example, takes this as a premise on the grounds that the universal Church is governed by the Holy Spirit who, as the Lord Jesus promised, would teach her ‘all truth’ (Jn 16:13).[21] He knew that the faith of the universal Church is authoritatively expressed by her prelates,[22] but he was also particularly interested in each believer’s personal instinct of faith, which he explored in relation to the theological virtue of faith.

c) Reformation and post-Reformation period

29. The challenge posed by the 16th century Reformers required renewed attention to the sensus fidei fidelium, and the first systematic treatment of it was worked out as a result. The Reformers emphasised the primacy of the word of God in Sacred Scripture (Scriptura sola) and the priesthood of the faithful. In their view, the internal testimony of the Holy Spirit gives all of the baptised the ability to interpret, by themselves, God’s word; this conviction did not discourage them, however, from teaching in synods and producing catechisms for the instruction of the faithful. Their doctrines called into question, among other things, the role and status of Tradition, the authority of the pope and the bishops to teach, and the inerrancy of councils. In response to their claim that the promise of Christ’s presence and the guidance of the Holy Spirit was given to the whole Church, not only to the Twelve but also to every believer,[23] Catholic theologians were led to explain more fully how the pastors serve the faith of the people. In the process, they gave increasing attention to the teaching authority of the hierarchy.

30. Theologians of the Catholic Reformation, building on previous efforts to develop a systematic ecclesiology, took up the question of revelation, its sources, and their authority. At first, they responded to the Reformers’ critique of certain doctrines by appealing to the infallibility of the whole Church, laity and clergy together, in credendo.[24] The Council of Trent, in fact, repeatedly appealed to the judgment of the whole Church in its defence of disputed articles of Catholic doctrine. Its Decree on the Sacrament of the Eucharist (1551), for example, specifically invoked ‘the universal understanding of the Church [universum Ecclesiae sensum]’.[25]

31. Melchior Cano (1509-1560), who attended the council, provided the first extended treatment of the sensus fidei fidelium in his defence of Catholic esteem for the probative force of Tradition in theological argument. In his treatise, De locis theologicis (1564),[26] he identified the present common consent of the faithful as one of four criteria for determining whether a doctrine or practice belongs to the apostolic tradition.[27] In a chapter on the Church’s authority with respect to doctrine, he argued that the faith of the Church cannot fail because she is the Spouse (Hos 2; 1Cor 11:2) and Body of Christ (Eph 5), and because the Holy Spirit guides her (Jn 14:16, 26).[28] Cano also noted that the word ‘Church’ sometimes designates all of the faithful, including the pastors, and sometimes designates her leaders and pastors (principes et pastores), for they too possess the Holy Spirit.[29] He used the word in the first sense when he asserted that the Church’s faith cannot fail, that the Church cannot be deceived in believing, and that infallibility belongs not only to the Church of past ages but also to the Church as it is presently constituted. He used ‘Church’ in the second sense when he taught that her pastors are infallible in giving authoritative doctrinal judgments, for they are assisted in this task by the Holy Spirit (Eph 4; 1 Tim 3).[30]

32. Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621), defending the Catholic faith against its Reformation critics, took the visible Church, the ‘universality of all believers’, as his starting point. For him, all that the faithful hold as de fide, and all that the bishops teach as pertaining to the faith, is necessarily true and to be believed.[31] He maintained that the councils of the Church cannot fail because they possess this consensus Ecclesiae universalis.[32]

33. Other theologians of the post-Tridentine era continued to affirm the infallibility of the Ecclesia (by which they meant the entire Church, inclusive of her pastors) in credendo, but began to distinguish the roles of the ‘teaching Church’ and the ‘learning Church’ rather sharply. The earlier emphasis on the ‘active’ infallibility of the Ecclesia in credendo was gradually replaced by an emphasis on the active role of the Ecclesia docens. It became common to say that the Ecclesia discens had only a ‘passive’ infallibility.

d) 19th Century

34. The 19th century was a decisive period for the doctrine of the sensus fidei fidelium. It saw, in the Catholic Church, partly in response to criticism from representatives of modern culture and from Christians of other traditions, and partly from an inner maturation, the rise of historical consciousness, a revival of interest in the Fathers of the Church and in medieval theologians, and a renewed exploration of the mystery of the Church. In this context, Catholic theologians such as Johann Adam Möhler (1796-1838), Giovanni Perrone (1794-1876), and John Henry Newman gave new attention to the sensus fidei fidelium as a locus theologicus in order to explain how the Holy Spirit maintains the whole Church in truth and to justify developments in the Church’s doctrine. Theologians highlighted the active role of the whole Church, especially the contribution of the lay faithful, in preserving and transmitting the Church’s faith; and the magisterium implicitly confirmed this insight in the process leading to the definition of the Immaculate Conception (1854).

35. To defend the Catholic faith against Rationalism, the Tübingen scholar, Johann Adam Möhler, sought to portray the Church as a living organism and to grasp the principles that governed the development of doctrine. In his view, it is the Holy Spirit who animates, guides, and unites the faithful as a community in Christ, bringing about in them an ecclesial ‘consciousness’ of the faith (Gemeingeist or Gesamtsinn), something akin to a Volksgeist or national spirit.[33] This sensus fidei, which is the subjective dimension of Tradition, necessarily includes an objective element, the Church’s teaching, for the Christian ‘sense’ of the faithful, which lives in their hearts and is virtually equivalent to Tradition, is never divorced from its content.[34]

36. John Henry Newman initially investigated the sensus fidei fidelium to resolve his difficulty concerning the development of doctrine. He was the first to publish an entire treatise on the latter topic, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), and to spell out the characteristics of faithful development. To distinguish between true and false developments, he adopted Augustine’s norm - the general consent of the whole Church, ‘Securus judicat orbis terrarum’ – but he saw that an infallible authority is necessary to maintain the Church in the truth.

37. Using insights from Möhler and Newman,[35] Perrone retrieved the patristic understanding of the sensus fidelium in order to respond to a widespread desire for a papal definition of Mary’s Immaculate Conception; he found in the unanimous consent, or conspiratio, of the faithful and their pastors a warrant for the apostolic origin of this doctrine. He maintained that the most distinguished theologians attributed probative force to the sensus fidelium, and that the strength of one ‘instrument of tradition’ can make up for the deficit of another, e.g., ‘the silence of the Fathers’.[36]

38. The influence of Perrone’s research on Pope Pius IX’s decision to proceed with the definition of the Immaculate Conception is evident from the fact that before he defined it the Pope asked the bishops of the world to report to him in writing regarding the devotion of their clergy and faithful people to the conception of the Immaculate Virgin.[37] In the apostolic constitution containing the definition, Ineffabilis Deus (1854), Pope Pius IX said that although he already knew the mind of the bishops on this matter, he had particularly asked the bishops to inform him of the piety and devotion of their faithful in this regard, and he concluded that ‘Holy Scripture, venerable Tradition, the constant mind of the Church [perpetuus Ecclesiae sensus], the remarkable agreement of Catholic bishops and the faithful [singularis catholicorum Antistitum ac fidelium conspiratio], and the memorable Acts and Constitutions of our predecessors’ all wonderfully illustrated and proclaimed the doctrine.[38] He thus used the language of Perrone’s treatise to describe the combined testimony of the bishops and the faithful. Newman highlighted the word, conspiratio, and commented: ‘the two, the Church teaching and the Church taught, are put together, as one twofold testimony, illustrating each other, and never to be divided’.[39]

39. When Newman later wrote On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine (1859), it was to demonstrate that the faithful (as distinct from their pastors) have their own, active role to play in conserving and transmitting the faith. ‘[T]he tradition of the Apostles’ is ‘committed to the whole Church in its various constituents and functions per modum unius’, but the bishops and the lay faithful bear witness to it in diverse ways. The tradition, he says, ‘manifests itself variously at various times: sometimes by the mouth of the episcopacy, sometimes by the doctors, sometimes by the people, sometimes by liturgies, rites, ceremonies, and customs, by events, disputes, movements, and all those other phenomena which are comprised under the name of history’.[40] For Newman, ‘there is something in the “pastorum et fidelium conspiratio” which is not in the pastors alone’.[41] In this work, Newman quoted at length from the arguments proposed over a decade earlier by Giovanni Perrone in favor of the definition of the Immaculate Conception.[42]

40. The First Vatican Council’s dogmatic constitution, Pastor Aeternus, in which the infallible magisterium of the pope was defined, by no means ignored the sensus fidei fidelium; on the contrary, it presupposed it. The original draft constitution, Supremi Pastoris, from which it developed, had a chapter on the infallibility of the Church (chapter nine).[43] When the order of business was changed in order to resolve the question of papal infallibility, however, discussion of that foundation was deferred and never taken up. In his relatio on the definition of papal infallibility, Bishop Vincent Gasser nevertheless explained that the special assistance given to the pope does not set him apart from the Church and does not exclude consultation and cooperation.[44] The definition of the Immaculate Conception was an example, he said, of a case ‘so difficult that the Pope deems it necessary for his information to inquire from the bishops, as the ordinary means, what is the mind of the churches’.[45] In a phrase intended to exclude Gallicanism, Pastor Aeternus asserted that ex cathedra doctrinal definitions of the pope concerning faith and morals are irreformable ‘of themselves and not from the consent of the Church [ex sese non autem ex consensu ecclesiae]’,[46] but that does not make the consensus Ecclesiae superfluous. What it excludes is the theory that such a definition requires this consent, antecedent or consequent, as a condition for its authoritative status.[47] In response to the Modernist crisis, a decree from the Holy Office, Lamentabili (1907), confirmed the freedom of the Ecclesia docens vis-à-vis the Ecclesia discens. The decree censured a proposition that would allow the pastors to teach only what the faithful already believed.[48]

e) 20th Century

41. Catholic theologians in the 20th century explored the doctrine of the sensus fidei fidelium in the context of a theology of Tradition, a renewed ecclesiology, and a theology of the laity. They emphasised that ‘the Church’ is not identical with her pastors; that the whole Church, by the action of the Holy Spirit, is the subject or ‘organ’ of Tradition; and that lay people have an active role in the transmission of the apostolic faith. The magisterium endorsed these developments both in the consultation leading to the definition of the glorious Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and in the Second Vatican Council’s retrieval and confirmation of the doctrine of the sensus fidei.

42. In 1946, following the pattern of his predecessor, Pope Pius XII sent an encyclical letter, Deiparae Virginis Mariae, to all the bishops of the world asking them to inform him ‘about the devotion of your clergy and people (taking into account their faith and piety) toward the Assumption of the most Blessed Virgin Mary’. He thus reaffirmed the practice of consulting the faithful in advance of making a dogmatic definition, and, in the apostolic constitution, Munificentissimus Deus (1950), he reported the ‘almost unanimous response’ he had received.[49] Belief in Mary’s Assumption was, indeed, ‘thoroughly rooted in the minds of the faithful’.[50] Pope Pius XII referred to ‘the concordant teaching of the Church’s ordinary doctrinal authority and the concordant faith of the Christian people’, and said, with regard now to belief in Mary’s Assumption, as Pope Pius IX had said with regard to belief in her Immaculate Conception, that there was a ‘singularis catholicorum Antistitum et fidelium conspiratio’. He added that the conspiratio showed ‘in an entirely certain and infallible way’ that Mary’s Assumption was ‘a truth revealed by God and contained in that divine deposit which Christ delivered to his Spouse to be guarded faithfully and to be taught infallibly’.[51] In both cases, then, the papal definitions confirmed and celebrated the deeply-held beliefs of the faithful.

43. Yves M.-J. Congar (1904-1995) contributed significantly to the development of the doctrine of the sensus fidei fidelis and the sensus fidei fidelium. In Jalons pour une Théologie du Laïcat (orig. 1953), he explored this doctrine in terms of the participation of the laity in the Church’s prophetical function. Congar was acquainted with Newman’s work and adopted the same scheme (i.e. the threefold office of the Church, and the sensus fidelium as an expression of the prophetic office) without, however, tracing it directly to Newman.[52] He described the sensus fidelium as a gift of the Holy Spirit ‘given to the hierarchy and the whole body of the faithful together’, and he distinguished the objective reality of faith (which constitutes the tradition) from the subjective aspect, the grace of faith.[53] Where earlier authors had underlined the distinction between the Ecclesia docens and the Ecclesia discens, Congar was concerned to show their organic unity. ‘The Church loving and believing, that is, the body of the faithful, is infallible in the living possession of the faith, not in a particular act or judgment’, he wrote.[54] The teaching of the hierarchy is at the service of communion.

44. In many ways, the Second Vatican Council’s teaching reflects Congar’s contribution. Chapter one of Lumen Gentium, on ‘The Mystery of the Church’, teaches that the Holy Spirit ‘dwells in the Church and in the hearts of the faithful, as in a temple’. ‘Guiding the Church in the way of all truth (cf. Jn 16:13) and unifying her in communion and in the works of ministry, he bestows upon her varied hierarchic and charismatic gifts, and in this way directs her; and he adorns her with his fruits (cf. Eph 4:11-12; 1Cor 12:4; Gal 5:22)’.[55] Chapter two then continues to deal with the Church as a whole, as the ‘People of God’, prior to distinctions between lay and ordained. The article (LG 12) which mentions the sensus fidei teaches that, having ‘an anointing that comes from the holy one (cf. 1Jn 2:20, 27)’, the ‘whole body of the faithful … cannot err in matters of belief’. The ‘Spirit of truth’ arouses and sustains a ‘supernatural appreciation of the faith [supernaturali sensu fidei]’, shown when ‘the whole people, … “from the bishops to the last of the faithful” … manifest a universal consent in matters of faith and morals’. By means of the sensus fidei, ‘the People of God, guided by the sacred teaching authority (magisterium), and obeying it, receives not the mere word of men, but truly the word of God (cf. 1Thess 2:13)’. According to this description, the sensus fidei is an active capacity or sensibility by which they are able to receive and understand the ‘faith once for all delivered to the saints (cf. Jude 3)’. Indeed, by means of it, the people not only ‘unfailingly adheres to this faith’, but also ‘penetrates it more deeply with right judgment, and applies it more fully in daily life’. It is the means by which the people shares in ‘Christ’s prophetic office’.[56]

45. Lumen Gentium subsequently describes, in chapters three and four, respectively, how Christ exercises his prophetic office not only through the Church’s pastors, but also through the lay faithful. It teaches that, ‘until the full manifestation of his glory’, the Lord fulfills this office ‘not only by the hierarchy who teach in his name and by his power, but also by the laity’. With regard to the latter, it continues: ‘He accordingly both establishes them as witnesses and provides them with the appreciation of the faith and the grace of the word [sensu fidei et gratia verbi instruit] (cf. Acts 2:17-18; Apoc 19:10) so that the power of the Gospel may shine out in daily family and social life.’ Strengthened by the sacraments, ‘the laity become powerful heralds of the faith in things to be hoped for (cf. Heb 11:1)’; ‘the laity can, and must, do valuable work for the evangelisation of the world’.[57] Here, the sensus fidei is presented as Christ’s gift to the faithful, and once again is described as an active capacity by which the faithful are able to understand, live and proclaim the truths of divine revelation. It is the basis for their work of evangelisation.

46. The sensus fidei is also evoked in the council’s teaching on the development of doctrine, in the context of the transmission of the apostolic faith. Dei Verbum says that the apostolic Tradition ‘makes progress in the Church, with the help of the Holy Spirit’. ‘There is a growth in insight into the realities and words that are being passed on’, and the council identifies three ways in which this happens: ‘through the contemplation and study of believers who ponder these things in their hearts (cf. Lk 2:19 and 51)’; ‘from the intimate sense of spiritual realities which they experience [ex intima spiritualium rerum quam experiuntur intelligentia]’; and ‘from the preaching of those [the bishops] who have received … the sure charism of truth’.[58] Although this passage does not name the sensus fidei, the contemplation, study, and experience of believers to which it refers are all clearly associated with the sensus fidei, and most commentators agree that the council fathers were consciously invoking Newman’s theory of the development of doctrine. When this text is read in light of the description of the sensus fidei in Lumen Gentium 12 as a supernatural appreciation of the faith, aroused by the Holy Spirit, by which people guided by their pastors adhere unfailingly to the faith, it is readily seen to express the same idea. When referring to ‘the remarkable harmony’ that should exist between the bishops and the faithful in the practice and profession of the faith handed on by the apostles, Dei Verbum actually uses the very expression found in the definitions of both Marian dogmas, ‘singularis fiat Antistitum et fidelium conspiratio’.[59]

47. Since the council, the magisterium has reiterated key points from the council’s teaching on the sensus fidei,[60] and also addressed a new issue, namely, the importance of not presuming that public opinion inside (or outside) the Church is necessarily the same thing as the sensus fidei (fidelium). In the post-synodal apostolic exhortation, Familiaris Consortio (1981), Pope John Paul II considered the question as to how the ‘supernatural sense of faith’ may be related to the ‘consensus of the faithful’ and to majority opinion as determined by sociological and statistical research. The sensus fidei, he wrote, ‘does not consist solely or necessarily in the consensus of the faithful’. It is the task of the Church’s pastors to ‘promote the sense of the faith in all the faithful, examine and authoritatively judge the genuineness of its expressions, and educate the faithful in an ever more mature evangelical discernment’.[61]

Chapter 2: The sensus fidei fidelis in the personal life of the believer

48. This second chapter concentrates on the nature of the sensus fidei fidelis. It utilises, in particular, the framework of arguments and categories offered by classical theology in order to reflect how faith is operative in individual believers. Although the Biblical vision of faith is larger, the classical understanding highlights an essential aspect: the adherence of the intellect, through love, to revealed truth. This conceptualisation of faith serves still today to clarify the understanding of the sensus fidei fidelis. In these terms, the chapter also considers some manifestations of the sensus fidei fidelis in the personal lives of believers, it being clear that the personal and ecclesial aspects of the sensus fidei are inseparable.

1. The sensus fidei as an instinct of faith

49. The sensus fidei fidelis is a sort of spiritual instinct that enables the believer to judge spontaneously whether a particular teaching or practice is or is not in conformity with the Gospel and with apostolic faith. It is intrinsically linked to the virtue of faith itself; it flows from, and is a property of, faith.[62] It is compared to an instinct because it is not primarily the result of rational deliberation, but is rather a form of spontaneous and natural knowledge, a sort of perception (aisthesis).

50. The sensus fidei fidelis arises, first and foremost, from the connaturality that the virtue of faith establishes between the believing subject and the authentic object of faith, namely the truth of God revealed in Christ Jesus. Generally speaking, connaturality refers to a situation in which an entity A has a relationship with another entity B so intimate that A shares in the natural dispositions of B as if they were its own. Connaturality permits a particular and profound form of knowledge. For example, to the extent that one friend is united to another, he or she becomes capable of judging spontaneously what suits the other because he or she shares the very inclinations of the other and so understands by connaturality what is good or bad for the other. This is a knowledge, in other words, of a different order than objective knowledge, which proceeds by way of conceptualisation and reasoning. It is a knowledge by empathy, or a knowledge of the heart.

51. Every virtue connaturalises its subject, in other words the one who possesses it, to its object, that is, to a certain type of action. What is meant by virtue here is the stable disposition (or habitus) of a person to behave in a certain way either intellectually or morally. Virtue is a kind of ‘second nature’, by which the human person constructs himself or herself by actualising freely and in accord with right reason the dynamisms inscribed in human nature. It thereby gives a definite, stable orientation to the activity of the natural faculties; it directs the latter to behaviours which the virtuous person henceforth accomplishes ‘naturally’, with ‘ease, self-mastery and joy’.[63]

52. Every virtue has a double effect: first, it naturally inclines the person who possesses it towards an object (a certain kind of action), and second, it spontaneously distances him or her from whatever is contrary to that object. For example, a person who has developed the virtue of chastity possesses a sort of ‘sixth sense’, ‘a kind of spiritual instinct’,[64] which enables him or her to discern the right way to behave even in the most complex situations, spontaneously perceiving what it is appropriate to do and what to avoid. A chaste person thereby instinctively adopts the right attitude, where the conceptual reasoning of the moralist might lead to perplexity and indecision.[65]

53. The sensus fidei is the form that the instinct which accompanies every virtue takes in the case of the virtue of faith. ‘Just as, by the habits of the other virtues, one sees what is becoming in respect of that habit, so, by the habit of faith, the human mind is directed to assent to such things as are becoming to a right faith, and not to assent to others.’[66]Faith, as a theological virtue, enables the believer to participate in the knowledge that God has of himself and of all things. In the believer, it takes the form of a ‘second nature’.[67]By means of grace and the theological virtues, believers become ‘participants of the divine nature’ (2Pet 1:4), and are in a way connaturalised to God. As a result, they react spontaneously on the basis of that participated divine nature, in the same way that living beings react instinctively to what does or does not suit their nature.

54. Unlike theology, which can be described as scientia fidei, the sensus fidei fidelis is not a reflective knowledge of the mysteries of faith which deploys concepts and uses rational procedures to reach its conclusions. As its name (sensus) indicates, it is akin rather to a natural, immediate and spontaneous reaction, and comparable to a vital instinct or a sort of ‘flair’ by which the believer clings spontaneously to what conforms to the truth of faith and shuns what is contrary to it.[68]

55. The sensus fidei fidelis is infallible in itself with regard to its object: the true faith.[69] However, in the actual mental universe of the believer, the correct intuitions of the sensus fidei can be mixed up with various purely human opinions, or even with errors linked to the narrow confines of a particular cultural context.[70]‘Although theological faith as such cannot err, the believer can still have erroneous opinions since all his thoughts do not spring from faith. Not all the ideas which circulate among the People of God are compatible with the faith.’[71]

56. The sensus fidei fidelis flows from the theological virtue of faith. That virtue is an interior disposition, prompted by love, to adhere without reserve to the whole truth revealed by God as soon as it is perceived as such. Faith does not therefore necessarily imply an explicit knowledge of the whole of revealed truth.[72]It follows that a certain type of sensus fidei can exist in ‘the baptised who are honoured by the name of Christian, but who do not however profess the Catholic faith in its entirety’.[73]The Catholic Church therefore needs to be attentive to what the Spirit may be saying to her by means of believers in the churches and ecclesial communities not fully in communion with her.

57. Since it is a property of the theological virtue of faith, the sensus fidei fidelis develops in proportion to the development of the virtue of faith. The more the virtue of faith takes root in the heart and spirit of believers and informs their daily life, the more the sensus fidei fidelis develops and strengthens in them. Now, since faith, understood as a form of knowledge, is based on love, charity is needed in order to animate it and to inform it, so as to make it a living and lived faith (fides formata). Thus, the intensifying of faith within the believer particularly depends on the growth within him or her of charity, and the sensus fidei fidelis is therefore proportional to the holiness of one’s life. St Paul teaches that ‘God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us’ (Rom 5:5), and it follows that the development of the sensus fidei in the spirit of the believer is particularly due to the action of the Holy Spirit. As the Spirit of love, who instils love in human hearts, the Holy Spirit opens to believers the possibility of a deeper and more intimate knowledge of Christ the Truth, on the basis of a union of charity: ‘Showing the truth is a property of the Holy Spirit, because it is love which brings about the revelation of secrets’.[74]

58. Charity enables the flourishing in believers of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, who leads them to a higher understanding of the things of faith ‘in all spiritual wisdom and understanding’ (Col 1:9).[75]In fact, the theological virtues attain their full measure in the believer’s life only when the believer allows the Holy Spirit to guide him or her (cf. Rom 8:14). The gifts of the Spirit are precisely the gratuitous and infused interior dispositions which serve as a basis for the activity of the Spirit in the life of the believer. By means of these gifts of the Spirit, especially the gifts of understanding and knowledge, believers are made capable of understanding intimately the ‘spiritual realities which they experience’,[76]and rejecting any interpretation contrary to the faith.

59. There is a vital interaction in each believer between the sensus fidei and the living of faith in the various contexts of his or her personal life. On one hand, the sensus fidei enlightens and guides the way in which the believer puts his or her faith into practice. On the other hand, by keeping the commandments and putting faith into practice, the believer gains a deeper understanding of faith: ‘those who do what is true come to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that their deeds have been done in God’ (Jn 3:21). Putting faith into practice in the concrete reality of the existential situations in which he or she is placed by family, professional and cultural relations enriches the personal experience of the believer. It enables him or her to see more precisely the value and the limits of a given doctrine, and to propose ways of refining its formulation. That is why those who teach in the name of the Church should give full attention to the experience of believers, especially lay people, who strive to put the Church’s teaching into practice in the areas of their own specific experience and competence.

2. Manifestations of the sensus fidei in the personal life of believers

60. Three principal manifestations of the sensus fidei fidelis in the personal life of the believer can be highlighted. The sensus fidei fidelis enables individual believers: 1) to discern whether or not a particular teaching or practice that they actually encounter in the Church is coherent with the true faith by which they live in the communion of the Church (see below, §§61-63); 2) to distinguish in what is preached between the essential and the secondary (§64); and 3) to determine and put into practice the witness to Jesus Christ that they should give in the particular historical and cultural context in which they live (§65).

61. ‘Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God ; for many false prophets have gone out into the world’ (1Jn 4:1). The sensus fidei fidelis confers on the believer the capacity to discern whether or not a teaching or practice is coherent with the true faith by which he or she already lives. If individual believers perceive or ‘sense’ that coherence, they spontaneously give their interior adherence to those teachings or engage personally in the practices, whether it is a matter of truths already explicitly taught or of truths not yet explicitly taught.

62. The sensus fidei fidelis also enables individual believers to perceive any disharmony, incoherence, or contradiction between a teaching or practice and the authentic Christian faith by which they live. They react as a music lover does to false notes in the performance of a piece of music. In such cases, believers interiorly resist the teachings or practices concerned and do not accept them or participate in them. ‘The habitus of faith possesses a capacity whereby, thanks to it, the believer is prevented from giving assent to what is contrary to the faith, just as chastity gives protection with regard to whatever is contrary to chastity.’[77]

63. Alerted by their sensus fidei, individual believers may deny assent even to the teaching of legitimate pastors if they do not recognise in that teaching the voice of Christ, the Good Shepherd. ‘The sheep follow [the Good Shepherd] because they know his voice. They will not follow a stranger, but they will run away from him because they do not know the voice of strangers’ (Jn 10:4-5). For St Thomas, a believer, even without theological competence, can and even must resist, by virtue of the sensus fidei, his or her bishop if the latter preaches heterodoxy.[78]In such a case, the believer does not treat himself or herself as the ultimate criterion of the truth of faith, but rather, faced with materially ‘authorised’ preaching which he or she finds troubling, without being able to explain exactly why, defers assent and appeals interiorly to the superior authority of the universal Church.[79]

64. The sensus fidei fidelis also enables the believer to distinguish in what is preached between what is essential for an authentic Catholic faith and what, without being formally against the faith, is only accidental or even indifferent with regard to the core of the faith. For example, by virtue of their sensus fidei, individual believers may relativise certain particular forms of Marian devotion precisely out of adherence to an authentic cult of the Virgin Mary. They might also distance themselves from preaching which unduly mixes together Christian faith and partisan political choices. By keeping the spirit of the believer focused in this way on what is essential to the faith, the sensus fidei fidelis guarantees an authentic Christian liberty (cf. Col 2:16-23), and contributes to a purification of faith.

65. Thanks to the sensus fidei fidelis and sustained by the supernatural prudence that the Spirit confers, the believer is able to sense, in new historical and cultural contexts, what might be the most appropriate ways in which to give an authentic witness to the truth of Jesus Christ, and moreover to act accordingly. The sensus fidei fidelis thus acquires a prospective dimension to the extent that, on the basis of the faith already lived, it enables the believer to anticipate a development or an explanation of Christian practice. Because of the reciprocal link between the practice of the faith and the understanding of its content, the sensus fidei fidelis contributes in this way to the emergence and illumination of aspects of the Catholic faith that were previously implicit; and because of the reciprocal link between the sensus fidei of the individual believer and the sensus fidei of the Church as such, that is the sensus fidei fidelium, such developments are never purely private, but always ecclesial. The faithful are always in relationship with one another, and with the magisterium and theologians, in the communion of the Church.

Chapter 3: The sensus fidei fidelium in the life of the Church

66. As the faith of the individual believer participates in the faith of the Church as a believing subject, so the sensus fidei (fidelis) of individual believers cannot be separated from the sensus fidei (fidelium) or ‘sensus Ecclesiae’[80] of the Church herself, endowed and sustained by the Holy Spirit,[81] and the consensus fidelium constitutes a sure criterion for recognising a particular teaching or practice as in accord with the apostolic Tradition.[82] The present chapter, therefore, turns to consider various aspects of the sensus fidei fidelium. It reflects, first of all, on the role of the latter in the development of Christian doctrine and practice; then on two relationships of great importance for the life and health of the Church, namely the relationship between the sensus fidei and the magisterium, and the relationship between the sensus fidei and theology; then, finally, on some ecumenical aspects of the sensus fidei.

1. The sensus fidei and the development of Christian doctrine and practice

67. The whole Church, laity and hierarchy together, bears responsibility for and mediates in history the revelation which is contained in the holy Scriptures and in the living apostolic Tradition. The Second Vatican Council stated that the latter form ‘a single sacred deposit of the word of God’ which is ‘entrusted to the Church’, that is, ‘the entire holy people, united to its pastors’.[83] The council clearly taught that the faithful are not merely passive recipients of what the hierarchy teaches and theologians explain; rather, they are living and active subjects within the Church. In this context, it underscored the vital role played by all believers in the articulation and development of the faith: ‘the Tradition that comes from the apostles makes progress in the Church, with the help of the Holy Spirit’.[84]

a) Retrospective and prospective aspects of the sensus fidei

68. In order to understand how it functions and manifests itself in the life of the Church, the sensus fidei needs to be viewed within the context of history, a history in which the Holy Spirit makes each day a day to hear the voice of the Lord afresh (cf. Heb 3:7-15). The Good News of the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ is transmitted to the Church as a whole through the living apostolic Tradition, of which the Scriptures are the authoritative written witness. Hence, by the grace of the Holy Spirit, who reminds the Church of all that Jesus said and did (cf. Jn 14:26), believers rely on the Scriptures and on the continuing apostolic Tradition in their life of faith and in the exercise of the sensus fidei.

69. However, faith and the sensus fidei are not only anchored in the past; they are also orientated towards the future. The communion of believers is a historical reality: ‘built upon the foundation of the apostles and the prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone’, it ‘grows into a holy temple in the Lord’ (Eph 2:20-21), in the power of the Holy Spirit, who guides the Church ‘into all the truth’ and declares to believers already now ‘the things that are to come’ (Jn 16:13), so that, especially in the Eucharist, the Church anticipates the return of the Lord and the coming of his kingdom (cf. 1Cor 11:26).

70. As she awaits the return of her Lord, the Church and her members are constantly confronted with new circumstances, with the progress of knowledge and culture, and with the challenges of human history, and they have to read the signs of the times, ‘to interpret them in the light of the divine Word’, and to discern how they may enable revealed truth itself to be ‘more deeply penetrated, better understood and more deeply presented’.[85] In this process, the sensus fidei fidelium has an essential role to play. It is not only reactive but also proactive and interactive, as the Church and all of its members make their pilgrim way in history. The sensus fidei is therefore not only retrospective but also prospective, and, though less familiar, the prospective and proactive aspects of the sensus fidei are highly important. The sensus fidei gives an intuition as to the right way forward amid the uncertainties and ambiguities of history, and a capacity to listen discerningly to what human culture and the progress of the sciences are saying. It animates the life of faith and guides authentic Christian action.

71. It can take a long time before this process of discernment comes to a conclusion. In the face of new circumstances, the faithful at large, pastors and theologians all have their respective roles to play, and patience and respect are needed in their mutual interactions if the sensus fidei is to be clarified and a true consensus fidelium, a conspiratio pastorum et fidelium, is to be achieved.

b) The contribution of the laity to the sensus fidelium

72. From the beginning of Christianity, all the faithful played an active role in the development of Christian belief. The whole community bore witness to the apostolic faith, and history shows that, when decisions about the faith needed to be taken, the witness of the laity was taken into consideration by the pastors. As has been seen in the historical survey above,[86] there is evidence that the laity played a major role in the coming into existence of various doctrinal definitions. Sometimes the people of God, and in particular the laity, intuitively felt in which direction the development of doctrine would go, even when theologians and bishops were divided on the issue. Sometimes there was a clear conspiratio pastorum et fidelium. Sometimes, when the Church came to a definition, the Ecclesia docens had clearly ‘consulted’ the faithful, and it pointed to the consensus fidelium as one of the arguments which legitimated the definition.

73. What is less well known, and generally receives less attention, is the role played by the laity with regard to the development of the moral teaching of the Church. It is therefore important to reflect also on the function played by the laity in discerning the Christian understanding of appropriate human behaviour in accordance with the Gospel. In certain areas, the teaching of the Church has developed as a result of lay people discovering the imperatives arising from new situations. The reflection of theologians, and then the judgment of the episcopal magisterium, was based on the Christian experience already clarified by the faithful intuition of lay people. Some examples might illustrate the role of the sensus fidelium in the development of moral doctrine:

i) Between canon 20 of the Council of Elvira (c. 306 AD), which forbade clerics and lay people to receive interest, and the response, Non esse inquietandos, of Pope Pius VIII to the bishop of Rennes (1830),[87] there is a clear development of teaching, due to both the emergence of a new awareness among lay people involved in business as well as new reflection on the part of theologians with regard to the nature of money.

ii) The openness of the Church towards social problems, especially manifest in Pope Leo XIII’s Encyclical Letter, Rerum Novarum (1896), was the fruit of a slow preparation in which lay ‘social pioneers’, activists as well as thinkers, played a major role.

iii) The striking albeit homogeneous development from the condemnation of ‘liberal’ theses in part 10 of the Syllabus of Errors (1864) of Pope Pius IX to the declaration on religious liberty, Dignitatis Humanae (1965), of Vatican II would not have been possible without the commitment of many Christians in the struggle for human rights.

The difficulty of discerning the authentic sensus fidelium in cases such as those above particularly indicates the need to identify dispositions required for authentic participation in the sensus fidei, dispositions which may serve, in turn, as criteria for discerning the authentic sensus fidei.[88]

2. The sensus fidei and the magisterium

a) The magisterium listens to the sensus fidelium

74. In matters of faith the baptised cannot be passive. They have received the Spirit and are endowed as members of the body of the Lord with gifts and charisms ‘for the renewal and building up of the Church’,[89] so the magisterium has to be attentive to the sensus fidelium, the living voice of the people of God. Not only do they have the right to be heard, but their reaction to what is proposed as belonging to the faith of the Apostles must be taken very seriously, because it is by the Church as a whole that the apostolic faith is borne in the power of the Spirit. The magisterium does not have sole responsibility for it. The magisterium should therefore refer to the sense of faith of the Church as a whole. The sensus fidelium can be an important factor in the development of doctrine, and it follows that the magisterium needs means by which to consult the faithful.

75. The connection between the sensus fidelium and the magisterium is particularly to be found in the liturgy. The faithful are baptised into a royal priesthood, exercised principally in the Eucharist,[90] and the bishops are the ‘high priests’ who preside at the Eucharist,[91] regularly exercising there their teaching office, also. The Eucharist is the source and summit of the life of the Church;[92] it is there especially that the faithful and their pastors interact, as one body for one purpose, namely to give praise and glory to God. The Eucharist shapes and forms the sensus fidelium and contributes greatly to the formulation and refinement of verbal expressions of the faith, because it is there that the teaching of bishops and councils is ultimately ‘received’ by the faithful. From early Christian times, the Eucharist underpinned the formulation of the Church’s doctrine because there most of all was the mystery of faith encountered and celebrated, and the bishops who presided at the Eucharist of their local churches among their faithful people were those who gathered in councils to determine how best to express the faith in words and formulas: lex orandi, lex credendi.[93]

b) The magisterium nurtures, discerns and judges the sensus fidelium

76. The magisterium of those ‘who have received, along with their right of succession in the episcopate, the sure charism of truth’[94] is a ministry of truth exercised in and for the Church, all of whose members have been anointed by the Spirit of truth (Jn 14:17; 15:26; 16:13; 1Jn 2:20, 27), and endowed with the sensus fidei, an instinct for the truth of the Gospel. Being responsible for ensuring the fidelity of the Church as a whole to the word of God, and for keeping the people of God faithful to the Gospel, the magisterium is responsible for nurturing and educating the sensus fidelium. Of course, those who exercise the magisterium, namely the pope and the bishops, are themselves, first of all, baptised members of the people of God, who participate by that very fact in the sensus fidelium.

77. The magisterium also judges with authority whether opinions which are present among the people of God, and which may seem to be the sensus fidelium, actually correspond to the truth of the Tradition received from the Apostles. As Newman said: ‘the gift of discerning, discriminating, defining, promulgating, and enforcing any portion of that tradition resides solely in the Ecclesia docens’.[95] Thus, judgement regarding the authenticity of the sensus fidelium belongs ultimately not to the faithful themselves nor to theology but to the magisterium. Nevertheless, as already emphasised, the faith which it serves is the faith of the Church, which lives in all of the faithful, so it is always within the communion life of the Church that the magisterium exercises its essential ministry of oversight.

c) Reception

78. ‘Reception’ may be described as a process by which, guided by the Spirit, the people of God recognises intuitions or insights and integrates them into the patterns and structures of its life and worship, accepting a new witness to the truth and corresponding forms of its expression, because it perceives them to be in accord with the apostolic Tradition. The process of reception is fundamental for the life and health of the Church as a pilgrim people journeying in history towards the fulness of God’s Kingdom.

79. All of the gifts of the Spirit, and in a special way the gift of primacy in the Church, are given so as to foster the unity of the Church in faith and communion,[96] and the reception of magisterial teaching by the faithful is itself prompted by the Spirit, as the faithful, by means of the sensus fidei that they possess, recognise the truth of what is taught and cling to it. As was explained above, the teaching of Vatican I that infallible definitions of the pope are irreformable ‘of themselves and not from the consent of the Church [ex sese non autem ex consensu ecclesiae]’[97] does not mean that the pope is cut off from the Church or that his teaching is independent of the faith of the Church.[98] The fact that prior to the infallible definitions both of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary and of her bodily Assumption into heaven an extensive consultation of the faithful was carried out at the express wish of the pope at that time amply proves the point.[99] What is meant, rather, is that such teaching of the pope, and by extension all teaching of the pope and of the bishops, is authoritative in itself because of the gift of the Holy Spirit, the charisma veritatis certum, that they possess.