1. AS the physical universe is sustained and carried on in dependence on certain centres of power and laws of operation, so the course of the social and political world, and of that great religious organization called the Catholic Church, is found to proceed for the most part from the presence or action of definite persons, places, events, and institutions, as the visible cause of the whole. There has been but one Judæa, one Greece, one Rome; one Homer, one Cicero; one Cæsar, one Constantine, one Charlemagne. And so, as regards Revelation, there has been one St. John the Divine, one Doctor of the Nations. Dogma runs along the line of Athanasius, Augustine, Thomas. The conversion of the heathen is ascribed, after the Apostles, to champions of the truth so few, that we may almost count them, such as Martin, Patrick, Augustine, Boniface. Then there is St. Antony, the father of monachism; St. Jerome, the interpreter of Scripture; St. Chrysostom, the great preacher.

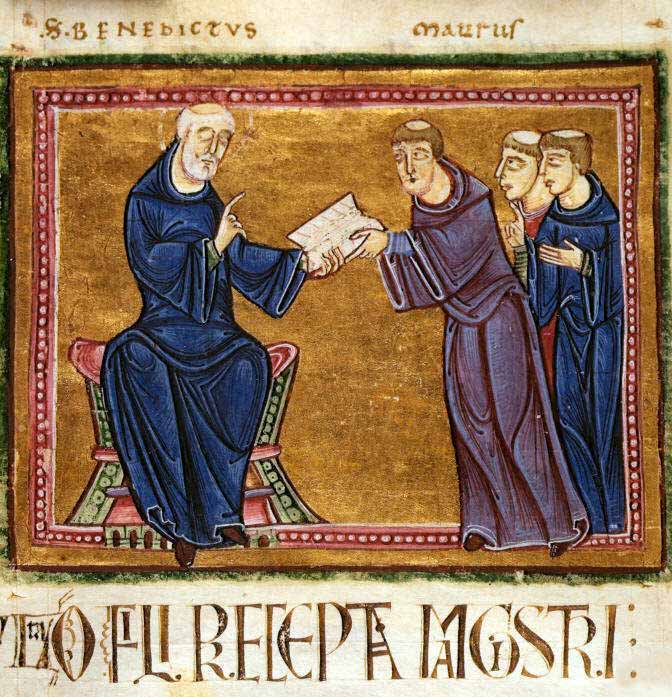

Education follows the same law: it has its history in Christianity, and its doctors or masters in that history. It has had three periods:—the ancient, the medieval, and the modern; and there are three Religious Orders in those periods respectively, which succeed, one the other, on its public stage, and represent the teaching {366} given by the Catholic Church during the time of their ascendancy. The first period is that long series of centuries, during which society was breaking or had broken up, and then slowly attempted its own re-construction; the second may be called the period of re-construction; and the third dates from the Reformation, when that peculiar movement of mind commenced, the issue of which is still to come. Now, St. Benedict has had the training of the ancient intellect, St. Dominic of the medieval; and St. Ignatius of the modern. And in saying this, I am in no degree disrespectful to the Augustinians, Carmelites, Franciscans, and other great religious families, which might be named, or to the holy Patriarchs who founded them; for I am not reviewing the whole history of Christianity, but selecting a particular aspect of it.

Perhaps as much as this will be granted to me without great hesitation. Next, I proceed to contrast these three great masters of Christian teaching with each other. To St. Benedict, then, who may fairly be taken to represent the various families of monks before his time and those which sprang from him (for they are all pretty much of one school), to this great Saint let me assign, for his discriminating badge, the element of Poetry; to St. Dominic, the Scientific element; and to St. Ignatius, the Practical.

These characteristics, which belong respectively to the schools of the three great Teachers, grow out of the circumstances under which they respectively entered upon their work. Benedict, entrusted with his mission almost as a boy, infused into it the romance and simplicity of boyhood. Dominic, a man of forty-five, a graduate in theology, a priest and a Canon, brought with him into religion that maturity and completeness of learning which {367} he had acquired in the schools. Ignatius, a man of the world before his conversion, transmitted as a legacy to his disciples that knowledge of mankind which cannot be learned in cloisters. And thus the three several Orders were (so to say), the births of Poetry, of Science, and Practical Sense.

And here another coincidence suggests itself. I have been giving these three attributes to the three Patriarchs whom I have specified, severally, from a bonâ-fide regard to their history, and without at all having any theory of philosophy in my eye. But after having so described them, it certainly did strike me that I had unintentionally been illustrating a somewhat popular notion of the day, the like of which is attributed to authors with whom I have as little sympathy as with any persons who can be named. According to these speculators, the life, whether of a race or of an individual of the great human family, is divided into three stages, each of which has its own ruling principle and characteristic. The youth makes his start in life, with "hope at the prow, and fancy at the helm;" he has nothing else but these to impel or direct him; he has not lived long enough to exercise his reason, or to gather in a store of facts; and, because he cannot do otherwise, he dwells in a world which he has created. He begins with illusions. Next, when at length he looks about for some surer footing than imagination gives him, he may have recourse to reason, or he may have recourse to facts; now facts are external to him, but his reason is his own: of the two, then, it is easier for him to exercise his reason than to ascertain facts. Accordingly, his first mental revolution, when he discards the life of aspiration and affection which has disappointed him, and the dreams of which he has been the sport and victim, is to embrace a life of {368} logic: this, then, is his second stage,—the metaphysical. He acts now on a plan, thinks by system, is cautious about his middle terms, and trusts nothing but what takes a scientific form. His third stage is when he has made full trial of life; when he has found his theories break down under the weight of facts, and experience falsify his most promising calculations. Then the old man recognizes at length, that what he can taste, touch, and handle, is trustworthy, and nothing beyond it. Thus he runs through his three periods of Imagination, Reason, and Sense; and then he comes to an end, and is not;—a most impotent and melancholy conclusion.

Undoubtedly a Catholic has no sympathy in so heartless a view of life, and yet it seems to square with what I have been saying of the three great Patriarchs of Christian teaching. And certainly there is a truth in it, which gives it its plausibility. However, I am not concerned here to do more than to put my finger on the point at which I should diverge from it, both in what I have been saying and what I must say concerning them. It is true then, that history, as viewed in these three Saints, is, somewhat after the manner of the theory I have mentioned, a progress from poetry through science to practical sense or prudence; but then this important proviso has to be borne in mind at the same time, that what the Catholic Church once has had, she never has lost. She has never wept over, or been angry with, time gone and over. Instead of passing from one stage of life to another, she has carried her youth and middle age along with her, on to her latest time. She has not changed possessions, but accumulated them, and has brought out of her treasure-house, according to the occasion, things new and old. She did not lose Benedict by finding Dominic; and she has still both Benedict and Dominic at home, though she {369} has become the mother of Ignatius. Imagination, Science, Prudence, all are good, and she has them all. Things incompatible in nature, cöexist in her; her prose is poetical on the one hand, and philosophical on the other.

Coming now to the historical proof of the contrast I have been instituting, I am sanguine in thinking that one branch of it is already allowed by the consent of the world, and is undeniable. By common consent, the palm of religious Prudence, in the Aristotelic sense of that comprehensive word, belongs to the School of Religion of which St. Ignatius is the Founder. That great Society is the classical seat and fountain (that is, in religious thought and the conduct of life, for of ecclesiastical politics I speak not), the school and pattern of discretion, practical sense, and wise government. Sublimer conceptions or more profound speculations may have been created or elaborated elsewhere; but, whether we consider the illustrious Body in its own constitution, or in its rules for instruction and direction, we see that it is its very genius to prefer this most excellent prudence to every other gift, and to think little both of poetry and of science, unless they happen to be useful. It is true that, in the long catalogue of its members, there are to be found the names of the most consummate theologians, and of scholars the most elegant and accomplished; but we are speaking here, not of individuals, but of the body itself. It is plain that the body is not over-jealous about its theological traditions, or it certainly would not suffer Suarez to controvert with Molina, Viva with Vasquez, Passaglia with Petavius, and Faure with Suarez, de Lugo, and Valentia. In this intellectual freedom its members justly glory; inasmuch as they have set their affections, not on the opinions of the Schools, but on the souls of men. And it {370} is the same charitable motive which makes them give up the poetry of life, the poetry of ceremonies,—of the cowl, the cloister, and the choir,—content with the most prosaic architecture, if it be but convenient, and the most prosaic neighbourhood, if it be but populous. I need not then dwell longer on this wonderful Religion, but may confine the remarks which are to follow to the two Religions which historically preceded it—the Benedictine and the Dominican [Note 1].

One preliminary more, suggested by a purely fanciful analogy:—As there are three great Patriarchs on the high road and public thoroughfare of Christian Education, so there were three chief Patriarchs in the first age of the chosen people. Putting aside Noe and Melchisedec, and Joseph and his brethren, we recognize three venerable fathers,—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and what are their characteristics? Abraham, the father of many nations; Isaac, the intellectual, living in solitary simplicity, and in loving contemplation; and Jacob, the persecuted and helpless, visited by marvellous providences, driven from place to place, set down and taken up again, ill-treated by those who were his debtors, suspected because of his sagacity, and betrayed by his eager faith, yet carried on and triumphing amid all troubles by means of his most faithful and powerful guardian-archangel.

2.

St. Benedict, then, like the great Hebrew Patriarch, was the "Father of many nations." He has been styled "the Patriarch of the West," a title which there are many reasons for ascribing to him. Not only was he the first to establish a perpetual Order of Regulars in {371} Western Christendom; not only, as coming first, has he had an ampler course of centuries for the multiplication of his children; but his Rule, as that of St. Basil in the East, is the normal rule of the first age of the Church, and was in time generally received even in communities which in no sense owed their origin to him. Moreover, out of his Order rose, in process of time, various new monastic families, which have established themselves as independent institutions, and are able in their turn to boast of the number of their houses, and the sanctity and historical celebrity of their members. He is the representative of Latin monachism for the long extent of six centuries, while monachism was one; and even when at length varieties arose, and distinct titles were given to them, the change grew out of him;—not the act of strangers who were his rivals, but of his own children, who did but make a new beginning in all devotion and loyalty to him. He died in the early half of the sixth century; at the beginning of the tenth rose from among his French monasteries the famous Congregation of Cluni, illustrated by St. Majolus, St. Odilo, Peter the Venerable, and other considerable personages, among whom is Hildebrand, afterwards Pope Gregory the Seventh. Then came, in long succession, the Orders or Congregations of Camaldoli under St. Romuald, of Vallombrosa, of Citeaux, to which St. Bernard has given his name, of Monte Vergine, of Fontvrault; those of England, Spain, and Flanders; the Silvestrines, the Celestines, the Olivetans, the Humiliati, besides a multitude of institutes for women, as the Gilbertines and the Oblates of St. Frances, and then at length, to mention no others, the Congregation of St. Maur in modern times, so well known for its biblical, patristical, and historical works, and for its learned members, Montfaucon, {372} Mabillon, and their companions. The panegyrists of this illustrious Order are accustomed to claim for it in all its branches as many as 37,000 houses, and, besides, 30 Popes, 200 Cardinals, 4 Emperors, 46 Kings, 51 Queens, 1,406 Princes, 1,600 Archbishops, 600 Bishops, 2,400 Nobles, and 15,000 Abbots and learned men [Note 2].

Nor are the religious bodies which sprang from St. Benedict the full measure of what he has accomplished,—as has been already observed. His Rule gradually made its way into those various monasteries which were of an earlier or of an independent foundation. It first coalesced with, and then supplanted, the Irish Rule of St. Columban in France, and the still older institutes which had been brought from the East by St. Athanasius, St. Eusebius, and St. Martin. At the beginning of the ninth century it was formally adopted throughout the dominions of Charlemagne. Pure, or with some admixture, it was brought by St. Augustine to England; and that admixture, if it existed, was gradually eliminated by St. Wilfrid, St. Dunstan, and Lanfranc, till at length it was received, with the name and obedience of St. Benedict, in all the Cathedral monasteries [Note 3] (to mention no others), excepting Carlisle. Nor did it cost such regular bodies any very great effort to make the change, even when historically most separate from St. Benedict; for the Saint had taken up for the most part what he found, and his Rule was but the expression of the genius of monachism in those first times of the Church, with a more exact adaptation to their needs than could elsewhere be met with. {373}

So uniform indeed had been the monastic idea before his time, and so little stress had been laid by individual communities on their respective peculiarities, that religious men passed at pleasure from one body to another [Note 4]. St. Benedict provides in his Rule for the case of strangers coming to one of his houses, and wishing to remain there. If such a one came from any monastery with which the monks had existing relations, then he was not to be received without letters from his Abbot; but, in the instance of "a foreign monk from distant parts," who wished to dwell with them as a guest, and was content with their ways, and conformed himself to them, and was not troublesome, "should he in the event wish to stay for good," says St. Benedict, "let him not be refused; for there has been room to make trial of him, during the time that hospitality has been shown to him: nay, let him even be invited to stay, that others may gain a lesson from his example; for in every place we are servants of one Lord and soldiers of one King." [Note 5]

3.

The unity of idea, which, as these words imply, is to be found in all monks in every part of Christendom, may be described as a unity of object, of state, and of occupation. Monachism was one and the same everywhere, because it was a reaction from that secular life, which has everywhere the same structure and the same characteristics. And, since that secular life contained in it many objects, many states, and many occupations, here was a special reason, as a matter of principle, why the reaction from it should bear the badge of unity, and {374} should be in outward appearance one and the same everywhere. Moreover, since that same secular life was, when monachism arose, more than ordinarily marked by variety, perturbation and confusion, it seemed on that very account to justify emphatically a rising and revolt against itself, and a recurrence to some state which, unlike itself, was constant and unalterable. It was indeed an old, decayed, and moribund world, into which Christianity had been cast. The social fabric was overgrown with the corruptions of a thousand years, and was held together, not so much by any common principle, as by the strength of possession and the tenacity of custom. It was too large for public spirit, and too artificial for patriotism, and its many religions did but foster in the popular mind division and scepticism. Want of mutual confidence would lead to despondency, inactivity, and selfishness. Society was in the slow fever of consumption, which made it restless in proportion as it was feeble. It was powerful, however, to seduce and deprave; nor was there any locus standi from which to combat its evils; and the only way of getting on with it was to abandon principle and duty, to take things as they came, and to do as the world did. Worse than all, this encompassing, entangling system of things, was, at the time we speak of, the seat and instrument of a paganism, and then of heresies, not simply contrary, but bitterly hostile, to the Christian profession. Serious men not only had a call, but every inducement which love of life and freedom could supply, to escape from its presence and its sway.

Their one idea then, their one purpose, was to be quit of it; too long had it enthralled them. It was not a question of this or that vocation, of the better deed, of the higher state, but of life and death. In later times {375} a variety of holy objects might present themselves for devotion to choose from, such as the care of the poor, or of the sick, or of the young, the redemption of captives, or the conversion of the barbarians; but early monachism was flight from the world, and nothing else. The troubled, jaded, weary heart, the stricken, laden conscience, sought a life free from corruption in its daily work, free from distraction in its daily worship; and it sought employments as contrary as possible to the world's employments,—employments, the end of which would be in themselves, in which each day, each hour, would have its own completeness;—no elaborate undertakings, no difficult aims, no anxious ventures, no uncertainties to make the heart beat, or the temples throb, no painful combination of efforts, no extended plan of operations, no multiplicity of details, no deep calculations, no sustained machinations, no suspense, no vicissitudes, no moments of crisis or catastrophe;—nor again any subtle investigations, nor perplexities of proof, nor conflicts of rival intellects, to agitate, harass, depress, stimulate, weary, or intoxicate the soul.

Hitherto I have been using negatives to describe what the primitive monk was seeking; in truth monachism was, as regards the secular life and all that it implies, emphatically a negation, or, to use another word, a mortification; a mortification of sense, and a mortification of reason. Here a word of explanation is necessary. The monks were too good Catholics to deny that reason was a divine gift, and had too much common sense to think to do without it. What they denied themselves was the various and manifold exercises of the reason; and on this account, because such exercises were excitements. When the reason is cultivated, it at once begins to combine, to centralize, to look forward, to look back, {376} to view things as a whole, whether for speculation or for action; it practises synthesis and analysis, it discovers, it invents. To these exercises of the intellect is opposed simplicity, which is the state of mind which does not combine, does not deal with premisses and conclusions, does not recognize means and their end, but lets each work, each place, each occurrence stand by itself,—which acts towards each as it comes before it, without a thought of anything else. This simplicity is the temper of children, and it is the temper of monks. This was their mortification of the intellect; every man who lives, must live by reason, as every one must live by sense; but, as it is possible to be content with the bare necessities of animal life, so is it possible to confine ourselves to the bare ordinary use of reason, without caring to improve it or make the most of it. These monks held both sense and reason to be the gifts of heaven, but they used each of them as little as they could help, reserving their full time and their whole selves for devotion;—for, if reason is better than sense, so devotion they thought to be better than either; and, as even a heathen might deny himself the innocent indulgences of sense in order to give his time to the cultivation of the reason, so did the monks give up reason, as well as sense, that they might consecrate themselves to divine meditation.

Now, then, we are able to understand how it was that the monks had a unity, and in what it consisted. It was a unity, I have said, of object, of state, and of occupation. Their object was rest and peace; their state was retirement; their occupation was some work that was simple, as opposed to intellectual, viz., prayer, fasting, meditation, study, transcription, manual labour, and other unexciting, soothing employments. Such was their institution all over the world; they had eschewed {377} the busy mart, the craft of gain, the money-changer's bench, and the merchant's cargo. They had turned their backs upon the wrangling forum, the political assembly, and the pantechnicon of trades. They had had their last dealings with architect and habit-maker, with butcher and cook; all they wanted, all they desired, was the sweet soothing presence of earth, sky, and sea, the hospitable cave, the bright running stream, the easy gifts which mother earth, "justissima tellus," yields on very little persuasion. "The monastic institute," says the biographer of St. Maurus, "demands Summa Quies, the most perfect quietness;" [Note 6] and where was quietness to be found, if not in reverting to the original condition of man, as far as the changed circumstances of our race admitted; in having no wants, of which the supply was not close at hand; in the "nil admirari;" in having neither hope nor fear of anything below; in daily prayer, daily bread, and daily work, one day being just like another, except that it was one step nearer than the day just gone to that great Day, which would swallow up all days, the day of everlasting rest.

4.

However, I have come into collision with a great authority, M. Guizot, and I must stop the course of my argument to make my ground good against him. M. Guizot, then, makes a distinction between monachism in its birth-place, in Egypt and Syria, and that Western institute, of which I have made St. Benedict the representative. He allows that the Orientals mortified the intellect, but he considers that Latin monachism was the seat of considerable mental activity. "The desire for retirement," he says, "for contemplation, for a marked {378} rupture with civilized society, was the source and fundamental trait of the Eastern monks: in the West, on the contrary, and especially in Southern Gaul, where, at the commencement of the fifth century, the principal monasteries were founded, it was in order to live in common, with a view to conversation as well as to religious edification, that the first monks met. The monasteries of Lerins, of St. Victor, and many others, were especially great schools of theology, the focus of intellectual movement. It was by no means with solitude or with mortification, but with discussion and activity, that they there concerned themselves." [Note 7] Great deference is due to an author so learned, so philosophical, so honestly desirous to set out Christianity to the best advantage; yet, I am at a loss to understand what has led him to make such a distinction between the East and West, and to assign to the Western monks an activity of intellect, and to the Eastern a love of retirement.

It is quite true that instances are sometimes to be found of monasteries in the West distinguished by much intellectual activity, but more, and more striking, instances are to be found of a like phenomenon in the East. If, then, such particular instances are to be taken as fair specimens of the state of Western monachism, they are equally fair specimens of the state of Eastern also; and the Eastern monks will be proved more intellectual than the Western, by virtue of that greater interest in doctrine and in controversy which given individuals or communities among them have exhibited. A very cursory reference to ecclesiastical history will be sufficient to show us that the fact is as I have stated it. The theological sensitiveness of the monks of Marseilles, Lerins, or Adrumetum, it seems, is to be a proof {379} of the intellectualism generally of the West: then, why is not the greater sensitiveness of the Scythian monks at Constantinople, and of their opponents, the Acœmetæ, an evidence in favour of the East? These two bodies of Religious actually came all the way from Constantinople to Rome to denounce one another, besieging, as it were, the Holy See, and the former of them actually attempting to raise the Roman populace against the Pope, in behalf of its own theological tenet. Does not this show activity of mind? I venture to say that, for one intellectual monk in the West, a dozen might be produced in the East. The very reproach, thrown out by secular historians against Greeks in general, of over-subtlety of intellect, applies in particular, if to any men, to certain classes or certain communities of Eastern monks. These were sometimes orthodox, quite as often heretical, but inexhaustible in their argumentative resources, whether the one or the other. If Pelagius be a monk in the West, on the other hand, Nestorius and Eutyches, both heresiarchs, are both monks in the East; and Eutyches, at the time of his heresy, was an old monk into the bargain, who had been thirty years abbot of a convent, and whom age, if not sanctity, might have saved from this abnormal use of his reason. His partizans were principally monks of Egypt; and they, coming up in force to the pseudo-synod of Ephesus, in aid of a theological thesis, kicked to death the patriarch of Constantinople, and put to flight the Legate of the Pope, all in consequence of their intellectual susceptibilities. A century earlier, Arius, on starting, carried away into his heresy as many as seven hundred nuns [Note 8]; what have the Western convents to show, in the way of controversial activity, comparable with a fact like this? I do {380} not insist on the zealous and influential orthodoxy of the monks of Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor in the fourth century, because it was probably nothing else but an honourable adhesion to the faith of the Church, without any serious exercise of mind; but turn to the great writers of Eastern Christendom, and consider how many of them figure at first sight as monks;—Chrysostom, Basil, Gregory Nazianzen, Epiphanius, Ephrem, Amphilochius, Isidore of Pelusium, Theodore, Theodoret, perhaps Athanasius. Among the Latin writers no great names occur to me but those of Jerome and Pope Gregory; I may add Paulinus, Sulpicius, Vincent, and Cassian, but Jerome is the only learned writer among them. I have a difficulty, then, even in comprehending, not to speak of admitting, M. Guizot's assertion, a writer who does not commonly speak without a meaning or a reason.

But, after all, however the balance of intellectualism may lie between certain convents or individuals in the East and the West, such particular instances of mental activity are nothing to the purpose, when taken to measure the state of the great body of the monks; certainly not in the West, with which in this paper I am exclusively concerned. In taking an estimate of the Benedictines, we need not trouble ourselves about the state of monachism in Egypt, Syria, Asia Minor, and Constantinople, as it existed after the fourth century, when the true monastic tradition was passing from the East to the West. In the fourth century, the Eastern Monks simply follow the defined and promulgated doctrine of the Church, and in following it are guilty of no exercise of reason; their intellectualism proper, which is foreign to the genius of their institute, begins with the fifth. Taking, then, the great tradition of St. Antony, St. Pachomius, and St. Basil in the East, and then tracing {381} it into the West by the hands of St. Athanasius, St. Martin, and their contemporaries, we shall find no historical facts but what admit of a fair explanation, consistent with the views which we have laid down above about monastic simplicity, bearing in mind always, what holds in all matters of fact, that there never was a rule without its exceptions.

5.

Every rule has its exceptions; but, further than this, when exceptions occur, they are commonly likely to be great ones. This is no paradox; illustrations of it are to be found everywhere. For instance, we may conceive a climate very fatal to children, and yet those who survive growing up to be strong men; and for a plain reason, because those alone could have passed the ordeal who had robust constitutions. Thus the Romans, so jealous of their freedom, when they resolved on the appointment of a supreme ruler for an occasion, did not do the thing by halves, but made him a Dictator. In like manner, a mere trifling occurrence, or an ordinary inward impulse, would be powerless to snap the bond which keeps the monk fast to his cell, his oratory, and his garden. Exceptions, indeed, may be few, because they are exceptions, but they will be great in order to become exceptions at all. It must be a serious emergence, a particular inspiration, a sovereign command, which brings the monk into political life; and he will be sure to make a great figure in it, else why should he have been torn from his cloister at all? This will account for the career of St. Gregory the Seventh or of St. Dunstan, of St. Bernard or of Abbot Suger, as far as it was political: the work they had to do was such as none could have done but a monk with his superhuman single-mindedness {382} and his pertinacity of purpose. Again, in the case of St. Boniface, the Apostle of Germany, and in that of others of the missionaries of his age, it seems to have been a particular inspiration which carried them abroad; and it is observable after all how soon most of them settled down into the mixed character of agriculturists and pastors in their new country, and resumed the tranquil life to which they had originally devoted themselves. As to the early Greek Fathers, some of those whom we have instanced above are only primâ facie exceptions, as Chrysostom, who, though he lived with the monks most austerely for as many as six years, can hardly be said to have taken on himself the responsibilities of their condition, or to have simply abandoned the world. Others of them, as Basil, were scholars, philosophers, men of the world, before they were monks, and could not put off their cultivation of mind or their learning with their secular dress; and these would be the very men, in an age when such talents were scarce, who would be taken out of their retirement by superior authority, and who therefore cannot fairly be quoted as ordinary specimens of the monastic life.

Exceptio probat regulam: let us see what two Doctors of the Church, one Greek, one Latin, both rulers, both monks, say concerning the state, which they at one time enjoyed, and afterwards lost. "You tell me," says St. Basil, writing to a friend from his solitude, "that it was little for me to describe the place of my retirement, unless I mentioned also my habits and my mode of life; yet really I am ashamed to tell you how I pass night and day in this lonely nook. I am like one who is angry with the size of his vessel, as tossing overmuch, and leaves it for the boat, and is seasick and miserable still. However, what I propose to do is as follows, with the hope {383} of tracing His steps who has said, 'If any one will come after Me, let him deny himself.' We must strive after a quiet mind. As well might the eye ascertain an object which is before it, while it roves up and down without looking steadily at it, as a mind, distracted with a thousand worldly cares, be able clearly to apprehend the truth. One who is not yoked in matrimony is harassed by rebellious impulses and hopeless attachments; he who is married is involved in his own tumult of cares: is he without children? he covets them; has he children? he has anxieties about their education. Then there is solicitude about his wife, care of his house, oversight of his servants, misfortunes in trade, differences with his neighbours, lawsuits, the merchant's risks, the farmer's toil. Each day, as it comes, darkens the soul in its own way; and night after night takes up the day's anxieties, and cheats us with corresponding dreams. Now, the only way of escaping all this is separation from the whole world, so as to live without city, home, goods, society, possessions, means of life, business, engagements, secular learning, that the heart may be prepared as wax for the impress of divine teaching. Solitude is of the greatest use for this purpose, as it stills our passions, and enables reason to extirpate them. Let then a place be found such as mine, separate from intercourse with men, that the tenor of our exercises be not interrupted from without. Pious exercises nourish the soul with divine thoughts. Soothing hymns compose the mind to a cheerful and calm state. Quiet, then, as I have said, is the first step in our sanctification; the tongue purified from the gossip of the world, the eyes unexcited by fair colour or comely shape, the ear secured from the relaxation of voluptuous songs, and that especial mischief, light jesting. Thus the mind, rescued from dissipation from {384} without, and sensible allurements, falls back upon itself, and thence ascends to the contemplation of God." [Note 9] It is quite clear that at least St. Basil took the same view of the monastic state as I have done.

So much for the East in the fourth century; now for the West in the seventh. "One day," says St. Gregory, after he had been constrained, against his own wish, to leave his cloister for the government of the Universal Church, "one day, when I was oppressed with the excessive trouble of secular affairs, I sought a retired place, friendly to grief, where whatever displeased me in my occupations might show itself, and all that was wont to inflict pain might be seen at one view." While he was in this retreat, his "most dear son, Peter," with whom, ever since the latter was a youth, he had been intimate, surprised him, and he opened his grief to him. "My sad mind," he said, "labouring under the soreness of its engagements, remembers how it went with me formerly in this monastery, how all perishable things were beneath it, how it rose above all that was transitory, and, though still in the flesh, went out in contemplation beyond that prison, so that it even loved death, which is commonly thought a punishment, as the gate of life and the reward of labour. But now, in consequence of the pastoral charge, it undergoes the busy work of secular men, and for that fair beauty of its quiet, is dishonoured with the dust of the earth. And often dissipating itself in outward things, to serve the many, even when it seeks what is inward, it comes home indeed, but is no longer what it used to be." [Note 10] Here is the very same view of the monastic state at Rome which St. Basil had in Pontus, viz., retirement and repose. There have been great Religious Orders since, whose atmosphere has been conflict, {385} and who have thriven in smiting or in being smitten. It has been their high calling; it has been their peculiar meritorious service; but, as for the Benedictine, the very air he breathes is peace.

6.

I have now said enough both to explain and to vindicate the biographer of St. Maurus, when he says that the object, and life, and reward of the ancient monachism was "summa quies,"—the absence of all excitement, sensible and intellectual, and the vision of Eternity. And therefore have I called the monastic state the most poetical of religious disciplines. It was a return to that primitive age of the world, of which poets have so often sung, the simple life of Arcadia or the reign of Saturn, when fraud and violence were unknown. It was a bringing back of those real, not fabulous, scenes of innocence and miracle, when Adam delved, or Abel kept sheep, or Noe planted the vine, and Angels visited them. It was a fulfilment in the letter, of the glowing imagery of prophets, about the evangelical period. Nature for art, the wide earth and the majestic heavens for the crowded city, the subdued and docile beasts of the field for the wild passions and rivalries of social life, tranquillity for ambition and care, divine meditation for the exploits of the intellect, the Creator for the creature, such was the normal condition of the monk. He had tried the world, and found its hollowness; or he had eluded its fellowship, before it had solicited him;—and so St. Antony fled to the desert, and St. Hilarion sought the sea shore, and St. Basil ascended the mountain ravine, and St. Benedict took refuge in his cave, and St. Giles buried himself in the forest, and St. Martin chose the broad river, in order that the world might be shut out {386} of view, and the soul might be at rest. And such a rest of intellect and of passion as this is full of the elements of the poetical.

I have no intention of committing myself here to a definition of poetry; I may be thought wrong in the use of the term; but, if I explain what I mean by it, no harm is done, whatever be my inaccuracy, and each reader may substitute for it some word he likes better. Poetry, then, I conceive, whatever be its metaphysical essence, or however various may be its kinds, whether it more properly belongs to action or to suffering, nay, whether it is more at home with society or with nature, whether its spirit is seen to best advantage in Homer or in Virgil, at any rate, is always the antagonist to science. As science makes progress in any subject-matter, poetry recedes from it. The two cannot stand together; they belong respectively to two modes of viewing things, which are contradictory of each other. Reason investigates, analyzes, numbers, weighs, measures, ascertains, locates, the objects of its contemplation, and thus gains a scientific knowledge of them. Science results in system, which is complex unity; poetry delights in the indefinite and various as contrasted with unity, and in the simple as contrasted with system. The aim of science is to get a hold of things, to grasp them, to handle them, to comprehend them; that is (to use the familiar term), to master them, or to be superior to them. Its success lies in being able to draw a line round them, and to tell where each of them is to be found within that circumference, and how each lies relatively to all the rest. Its mission is to destroy ignorance, doubt, surmise, suspense, illusions, fears, deceits, according to the "Felix qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas" of the Poet, whose whole passage, by the way, may be taken as drawing {387} out the contrast between the poetical and the scientific [Note 11]. But as to the poetical, very different is the frame of mind which is necessary for its perception. It demands, as its primary condition, that we should not put ourselves above the objects in which it resides, but at their feet; that we should feel them to be above and beyond us, that we should look up to them, and that, instead of fancying that we can comprehend them, we should take for granted that we are surrounded and comprehended by them ourselves. It implies that we understand them to be vast, immeasurable, impenetrable, inscrutable, mysterious; so that at best we are only forming conjectures about them, not conclusions, for the phenomena which they present admit of many explanations, and we cannot know the true one. Poetry does not address the reason, but the imagination and affections; it leads to admiration, enthusiasm, devotion, love. The vague, the uncertain, the irregular, the sudden, are among its attributes or sources. Hence it is that a child's mind is so full of poetry, because he knows so little; and an old man of the world so devoid of poetry, because his experience of facts is so wide. Hence it is that nature is commonly more poetical than art, in spite of Lord Byron, because it is less comprehensible and less patient of definitions; history more poetical than philosophy; the savage than the citizen; the knight-errant than the brigadier-general; the winding bridle-path than the {388} straight railroad; the sailing vessel than the steamer; the ruin than the spruce suburban box; the Turkish robe or Spanish doublet than the French dress coat. I have now said far more than enough to make it clear what I mean by that element in the old monastic life, to which I have given the name of the Poetical.

Now, in many ways the family of St. Benedict answers to this description, as we shall see if we look into its history. Its spirit indeed is ever one, but not its outward circumstances. It is not an Order proceeding from one mind at a particular date, and appearing all at once in its full perfection, and in its extreme development, and in form one and the same everywhere and from first to last, as is the case with other great religious institutions; but it is an organization, diverse, complex, and irregular, and variously ramified, rich rather than symmetrical, with many origins and centres and new beginnings and the action of local influences, like some great natural growth; with tokens, on the face of it, of its being a divine work, not the mere creation of human genius. Instead of progressing on plan and system and from the will of a superior, it has shot forth and run out as if spontaneously, and has shaped itself according to events, from an irrepressible fulness of life within, and from the energetic self-action of its parts, like those symbolical creatures in the prophet's vision, which "went every one of them straight forward, whither the impulse of the spirit was to go." It has been poured out over the earth, rather than been sent, with a silent mysterious operation, while men slept, and through the romantic adventures of individuals, which are well nigh without record; and thus it has come down to us, not risen up among us, and is found rather than established. Its separate and scattered monasteries occupy the land, {389} each in its place, with a majesty parallel, but superior, to that of old aristocratic houses. Their known antiquity, their unknown origin, their long eventful history, their connection with Saints and Doctors when on earth, the legends which hang about them, their rival ancestral honours, their extended sway perhaps over other religious houses, their hold upon the associations of the neighbourhood, their traditional friendships and compacts with other great landlords, the benefits they have conferred, the sanctity which they breathe,—these and the like attributes make them objects, at once of awe and of affection.

7.

Such is the great Abbey of Bobbio, in the Apennines, where St. Columban came to die, having issued with his twelve monks from his convent in Benchor, county Down, and having spent his life in preaching godliness and planting monasteries in half-heathen France and Burgundy. Such St. Gall's, on the lake of Constance, so called from another Irishman, one of St. Columban's companions, who remained in Switzerland, when his master went on into Italy. Such the Abbey of Fulda, where lies St. Boniface, who, burning with zeal for the conversion of the Germans, attempted them a first time and failed, and then a second time and succeeded, and at length crowned the missionary labours of forty-five years with martyrdom. Such Monte Cassino, the metropolis of the Benedictine name, where the Saint broke the idol, and cut down the grove, of Apollo. Ancient houses such as these subdue the mind by the mingled grandeur and sweetness of their presence. They stand in history with an accumulated interest upon them, which belongs to no other monuments of {390} the past. Whatever there is of venerable authority in other foundations, in Bishops' sees, in Cathedrals, in Colleges, respectively, is found in combination in them. Each gate and cloister has had its own story, and time has engraven upon their walls the chronicle of its revolutions. And, even when at length rudely destroyed, or crumbled into dust, they live in history and antiquarian works, in the pictures and relics which remain of them, and in the traditions of their place.

In the early part of last century the Maurist Fathers, with a view of collecting materials for the celebrated works which they had then on hand, sent two of their number on a tour through France and the adjacent provinces. Among other districts the travellers passed through the forest of Ardennes, which has been made classical by the prose of Cæsar, and the poetry of Shakespeare. There they found the great Benedictine Convent of St. Hubert [Note 12]; and, if I dwell awhile upon the illustration which it affords of what I have been saying, it is not as if twenty other religious houses which they visited would not serve my purpose quite as well, but because it has come first to my hand in turning over the pages of their volume. At that time the venerable abbey in question had upon it the weight of a thousand years, and was eminent above others in the country in wealth, in privileges, in name, and, not the least recommendation, in the sanctity of its members. The lands on which it was situated were its freehold, and their range included sixteen villages. The old chronicle informs us that, about the middle of the seventh century, {391} St. Sigibert, the Merovingian, pitched upon Ardennes and its neighbourhood for the establishment of as many as twelve monasteries, with the hope of thereby obtaining from heaven an heir to his crown. Dying prematurely, he but partially fulfilled his pious intention, which was taken up by Pepin, sixty years afterwards, at the instance of his chaplain, St. Beregise; so far, at least, as to make a commencement of the abbey of which we are speaking. Beregise had been a monk of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Tron, and he chose for the site of the new foundation a spot in the midst of the forest, marked by the ruins of a temple dedicated to the pagan Diana, the goddess of the chase. The holy man exorcised the place with the sign of the Cross; and, becoming abbot of the new house, filled it either with monks, or, as seems less likely, with secular canons. From that time to the summer day, when the two Maurists visited it, the sacred establishment, with various fortunes, had been in possession of the land.

On entering its precincts, they found it at once full and empty: empty of the monks, who were in the fields gathering in the harvest; full of pilgrims, who were wont to come day after day, in never-failing succession, to visit the tomb of St. Hubert. What a series of events has to be recorded to make this simple account intelligible! and how poetical is the picture which it sets before us, as well as those events themselves, which it presupposes, when they come to be detailed! Were it not that I should be swelling a passing illustration into a history, I might go on to tell how strict the observance of the monks had been for the last hundred years before the travellers arrived there, since Abbot Nicholas de Fanson had effected a reform on the pattern of the French Congregation of St. Vanne. I might relate {392} how, when a simple monk in the Abbey of St. Hubert, Nicholas had wished to change it for a stricter community, and how he got leave to go off to the Congregation just mentioned, and how then his old Abbot died suddenly, and how he himself to his surprise was elected in his place. And I might tell how, when his mitre was on his head, he set about reforming the house which he had been on the point of quitting, and how he introduced for that purpose two monks of St. Vanne; and how the Bishop of Liege, in whose diocese he was, set himself against his holy design, and how some of the old monks attempted to poison him; and how, though he carried it into effect, still he was not allowed to aggregate his Abbey to the Congregation whose reform he had adopted; but how his good example encouraged the neighbouring abbeys to commence a reform in themselves, which issued in an ecclesiastical union of the Flemish Houses.

All this, however, would not have been more than one passage, of course, in the adventures which had befallen the abbey and its abbots in the course of its history. It had had many seasons of decay before the time of Nicholas de Fanson, and many restorations, and from different quarters. None of them was so famous or important as the reform effected in the year 817, about a century after its original foundation, when the secular canons, who anyhow had got in, were put out, and the monks put in their place, at the instance of the then Bishop of Liege, who had a better spirit than his successor in the time of Nicholas. The new inmates were joined by some persons of noble birth from the Cathedral, and by their suggestion and influence the bold measure was taken of attempting to gain from Liege the body of the great St. Hubert, the Apostle of Ardennes. {393) Great, we may be sure, was the resistance of the city where he lay; but Abbot Alreus, the friend and fellow-workman of St. Benedict of Anian, the first Reformer of the Benedictine Order before the date of Cluni, went to the Bishop, and he went to the Archbishop of Cologne; and then both prelates went to the Emperor Louis le Debonnaire, the son of Charlemagne, whose favourite hunting ground the forest was; and he referred the matter to the great Council of Aix-la-Chapelle, whence a decision came in favour of the monks of Ardennes. So with great solemnity the sacred body was conveyed by water to its new destination; and there in the Treasury, in memorial of the happy event, the Maurist visitors saw the very chalice of gold, and the beautiful copy of the Gospels, ornamented with precious stones, given to the Abbey by Louis at the time. Doubtless it was the handiwork of the monks of some other Benedictine House, as must have been the famous Psalter, of which the visitors speak also, written in letters of gold, the gift of Louis's son, the Emperor Lothaire; and there he sits in the first page, with his crown on his head, his sceptre in one hand, his sheathed sword in the other, and something very like a fleur-de-lys buckling on his ermine robe at the shoulder:—which precious gift, that is, the Psalter with all its pictures, two centuries after came most unaccountably into the possession of the Lady Helvidia of Aspurg, who gave it to her young son Bruno, afterwards Pope Leo the Ninth, to learn the Psalms by; but, as the young Saint made no progress in his task, she came to the conclusion that she had no right to the book, and so she ended by making a pilgrimage to St. Hubert with Bruno, and, not only gave back the Psalter, but made the offering of a Sacramentary besides. {394}

But to return to the relics of the Saint; the sacred body was taken by water up the Maes. The coffin was of marble, and perhaps could have been taken no other way; but another reason, besides its weight, lay in the indignation of the citizens of Liege, who might have interfered with a land journey, and in fact did make several attempts, in the following years, to regain the body. In consequence, the good monks of Ardennes hid it within the walls of their monastery, confiding the secret of its whereabouts to only two of their community at a time; and they showed in the sacristy to the devout, instead, the Saint's ivory cross and his stole, the sole of his shoe and his comb, and Diana, Marchioness of Autrech, gave a golden box to hold the stole. This, however, was in after times; for they were very loth at first to let strangers within their cloisters at all; and in 838, when a long spell of rain was destroying the crops, and the people of the neighbourhood came in procession to the shrine to ask the intercession of the Saint, the cautious Abbot Sewold, availing himself of the Rule, would only admit priests, and them by threes and fours, with naked feet, and a few laymen with each of them. The supplicants were good men, however, and had no notion of playing any trick: they came in piety and devotion, and the rain ceased, and the country was the gainer by St. Hubert of Ardennes. And thenceforth others, besides the monks, became interested in his stay in the forest.

And now I have said something in explanation why the courtyard was full of pilgrims when the travellers came. St. Hubert had been an object of devotion for a particular benefit, perhaps ever since he came there, certainly as early as the eleventh century, for we then have historical notice of it. His preference of the forest to the city, which he had shown in his life-time before his {395} conversion, was illustrated by the particular grace or miraculous service, for which, more than for any other, he used his glorious intercession on high. He is famous for curing those who had suffered from the bite of wild animals, especially dogs of the chase, and a hospital was attached to the Abbey for their reception. The sacristan of the Church officiated in the cure; and with rites which never indeed failed, but which to some cautious persons seemed to savour of superstition. Certainly they were startling at first sight; accordingly a formal charge on that score was at one time brought against them before the Bishop of Liege, and a process followed. The Bishop, the University of Louvain, and its Faculty of Medicine, conducted the inquiry, which was given in favour of the Abbey, on the ground that what looked like a charm might be of the nature of a medical regimen.

However, though the sacristan was the medium of the cure, the general care of the patients was left to externs. The hospital was served by secular priests, since the monks heard no confessions save those of their own people. This rule they observed, in order to reserve themselves for the proper duties of a Benedictine,—the choir, study, manual labour, and transcription of books; and, while the Maurists were ocular witnesses of their agricultural toils, they saw the diligence of their penmanship in its results, for the MSS. of their Library were the choicest in the country. Among them, they tell us, were copies of St. Jerome's Bible, the Acts of the Councils, Bede's History, Gregory and Isidore, Origen and Augustine.

The Maurists report as favourably of the monastic buildings themselves as of the hospital and library. Those buildings were a chronicle of past times, and of the changes which had taken place in them. First there {396} were the poor huts of St. Beregise upon the half-cleared and still marshy ground of the forest; then came the building of a sufficient house, when St. Hubert was brought there; and centuries after that, St. Thierry, the intimate friend of the great Pope Hildebrand, had renewed it magnificently, at the time that he was Abbot. He was sadly treated in his lifetime by his monks, as Nicholas after him; but, after his death, they found out that he was a Saint, which they might have discovered before it; and they placed him in the crypt, and there he and another holy Abbot after him lay in peace, till the Calvinists broke into it in the sixteenth century, and burned both of them to ashes. There were marks too of the same fanatics on the pillars of the nave of the Church; which had been built by Abbot John de Wahart in the twelfth century, and then again from its foundations by Abbots Nicholas de Malaise and Romaclus, the friend of Blosius, four centuries later; and it was ornamented by Abbot Cyprian, who was called the friend of the poor; and doubtless the travellers admired the marble of the choir and sanctuary, and the silver candelabra of the altar given by the reigning Lord Abbot; and perhaps they heard him sing solemn Mass on the Assumption, as was usual with him on that feast, with his four secular chaplains, one to carry his Cross, another his mitre, a third his gremial, and a fourth his candle, and accompanied by the pealing organ and the many musical bells, which had been the gift of Abbot Balla about a hundred years earlier. Can we imagine a more graceful union of human with divine, of the sweet with the austere, of business and of calm, of splendour and of simplicity, than is displayed in a great religious house after this pattern, when unrelaxed in its observance, and pursuing the ends for which it was endowed? {397}

8.

The monks have been accused of choosing beautiful spots for their dwellings; as if this were a luxury in ascetics, and not rather the necessary alleviation of their asceticism. Even when their critics are kindest, they consider such sites as chosen by a sort of sentimental, ornamental indolence. "Beaulieu river," says Mr. Warner in his topography of Hampshire, and, because he writes far less ill-naturedly than the run of authors, I quote him, "Beaulieu river is stocked with plenty of fish, and boasts in particular of good oysters and fine plaice, and is fringed quite to the edge of the water with the most beautiful hanging woods. In the area enclosed are distinct traces of various fishponds, formed for the use of the convent. Some of them continue perfect to the present day, and abound with fish. A curious instance occurs also of monkish luxury, even in the article of water; to secure a fine spring those monastics have spared neither trouble nor expense. About half a mile to the south-east of the Abbey is a deep wood; and at a spot almost inaccessible is a cave formed of smooth stones. It has a very contracted entrance, but spreads gradually into a little apartment, of seven feet wide, ten deep, and about five high. This covers a copious and transparent spring of water, which, issuing from the mouth of the cave, is lost in a deep dell, and is there received, as I have been informed, by a chain of small stone pipes, which formerly, when perfect, conveyed it quite to the Abbey. It must be confessed the monks in general displayed an elegant taste in the choice of their situations. Beaulieu Abbey is a striking proof of this. Perhaps few spots in the kingdom could have been pitched upon better calculated for monastic seclusion {398} than this. The deep woods, with which it is almost environed, throw an air of gloom and solemnity over the scene, well suited to excite religious emotions; while the stream that glides by its side afforded to the recluse a striking emblem of human life: and at the same time that it soothed his mind by a gentle murmuring, led it to serious thought by its continual and irrevocable lesson." [Note 13]

The monks were not so soft as all this, after all; and if Mr. Warner had seen them, we may be sure he would have been astonished at the stern, as well as sweet simplicity which characterized them. They were not dreamy sentimentalists, to fall in love with melancholy winds and purling rills, and waterfalls and nodding groves; but their poetry was the poetry of hard work and hard fare, unselfish hearts and charitable hands. They could plough and reap, they could hedge and ditch, they could drain; they could lop, they could carpenter; they could thatch, they could make hurdles for their huts; they could make a road, they could divert or secure the streamlet's bed, they could bridge a torrent. Mr. Warner mentions one of their luxuries,—clear, wholesome water; it was an allowable one, especially as they obtained it by their own patient labour. If their grounds are picturesque, if their views are rich, they made them so, and had, we presume, a right to enjoy the work of their own hands. They found a swamp, a moor, a thicket, a rock, and they made an Eden in the wilderness. They destroyed snakes; they extirpated wild cats, wolves, boars, bears; they put to flight or they converted rovers, outlaws, robbers. The gloom of the forest departed, and the sun, for the first time since the Deluge {399} shone upon the moist ground. St. Benedict is the true man of Ross.

Who hung with woods yon mountain's sultry brow?

From the dry rock who made the waters flow?

Whose causeway parts the vale with shady rows?

Whose seats the weary traveller repose?

He feeds yon almshouse, neat, but void of state,

When Age and Want sit smiling at the gate;

Him portioned maids, apprenticed orphans blessed,

The young who labour, and the old who rest.

And candid writers, though not Catholics, allow it. Even English, and much more foreign historians and antiquarians, have arrived at a unanimous verdict here. "We owe the agricultural restoration of great part of Europe to the monks," says Mr. Hallam. "The monks were much the best husbandmen, and the only gardeners," says Forsyth. "None," says Wharton, "ever improved their lands and possessions more than the monks, by building, cultivating, and other methods." The cultivation of Church lands, as Sharon Turner infers from Doomsday Book, was superior to that held by other proprietors, for there was less wood upon them, less common pasture, and more abundant meadow. "Wherever they came," says Mr. Soame on Mosheim, "they converted the wilderness into a cultivated country; they pursued the breeding of cattle and agriculture, laboured with their own hands, drained morasses, and cleared away forests. By them Germany was rendered a fruitful country." M. Guizot speaks as strongly: "The Benedictine monks were the agriculturists of Europe; they cleared it on a large scale, associating agriculture with preaching." [Note 14] {400}

St. Benedict's direct object indeed in setting his monks to manual labour was neither social usefulness nor poetry, but penance; still his work was both the one and the other. The above-cited authors enlarge upon its use, and I in what I am writing may be allowed to dwell upon its poetry; we may contemplate both its utility to man and its service to God in the aspect of its poetry. How romantic then, as well as useful, how lively as well as serious, is their history, with its episodes of personal adventure and prowess, its pictures of squatter, hunter, farmer, civil engineer, and evangelist united in the same individual, with its supernatural colouring of heroic virtue and miracle! When St. Columban first came into Burgundy with his twelve young monks, he placed himself in a vast wilderness, and made them set about cultivating the soil. At first they all suffered from hunger, and were compelled to live on the barks of trees and wild herbs. On one occasion they were for five days in this condition. St. Gall, one of them, betook himself to a Swiss forest, fearful from the multitude of wild beasts; and then, choosing the neighbourhood of a mountain stream, he made a cross of twigs, and hung some relics on it, and laid the foundation of his celebrated abbey. St. Ronan came from Ireland to Cornwall, and chose a wood, full of wild beasts, for his hermitage, near the Lizard. The monks of St. Dubritius, the founder of the Welsh Schools, also sought the woods, and there they worked hard at manufactures, agriculture, and road making. St. Sequanus placed himself where "the trees almost touched the clouds." He and his companions, when they first explored it, asked themselves how they could penetrate into it, when they saw a winding footpath, so narrow and full of briars that it was with difficulty that one foot followed another. With much labour {401} and with torn clothes they succeeded in gaining its depths, and stooping their heads into the darkness at their feet, they perceived a cavern, shrouded by the thick interlacing branches of the trees, and blocked up with stones and underwood. "This," says the monastic account, "was the cavern of robbers, and the resort of evil spirits." Sequanus fell on his knees, prayed, made the sign of the Cross over the abyss, and built his cell there. Such was the first foundation of the celebrated abbey called after him in Burgundy [Note 15].

Sturm, the Bavarian convert of St. Boniface, was seized with a desire, as his master before him in his English monastery, of founding a religious house in the wilds of Pagan Germany; and setting out with two companions, he wandered for two days through the Buchonian forest, and saw nothing but earth, sky, and large trees. On the third day he stopped and chose a spot, which on trial did not answer. Then, mounting an ass, he set out by himself, cutting down branches of a night to secure himself from the wild beasts, till at length he came to the place (described by St. Boniface as "locum silvaticum in eremo, vastissimæ solitudinis"), in which afterwards arose the abbey and schools of Fulda. Wunibald was suspicious of the good wine of the Rhine where he was, and, determining to leave it, he bought the land where Heidensheim afterwards stood, then a wilderness of trees and underwood, covering a deep valley and the sides of lofty mountains. There he proceeded, axe in hand, to clear the ground for his religious house, while the savage natives looked on sullenly, jealous for their hunting-grounds and sacred trees. Willibald, {402} his brother, had pursued a similar work on system; he had penetrated his forest in every direction and scattered monasteries over it. The Irish Alto pitched himself in a wood, half way between Munich and Vienna. Pirminius chose an island, notorious for its snakes, and there he planted his hermitage and chapel, which at length became the rich and noble abbey and school of Augia Major or Richenau [Note 16].

The more celebrated School of Bec had a similar beginning at a later date, when Herluin, an old soldier, devoted his house and farm to an ecclesiastical purpose, and governed, as abbot, the monastery which he had founded. "You might see him," says the writer of his life, "when office was over in church, going out to his fields, at the head of his monks, with his bag of seed about his neck, and his rake or hoe in his hand. There he remained with them hard at work till the day was closing. Some were employed in clearing the land of brambles and weeds; others spread manure; others were weeding or sowing; no one ate his bread in idleness. Then when the hour came for saying office in church, they all assembled together punctually. Their ordinary food was rye bread and vegetables with salt and water; and the water muddy, for the well was two miles off." [Note 17] Lanfranc, then a secular, was so edified by the simple Abbot, fresh from the field, setting about his baking with dirty hands, that he forthwith became one of the party [Note 18]; and, being unfitted for labour, opened in the house a school of logic, thereby to make money for the community. Such was the cradle of the scholastic theology; the last years of the patristic, which were {403} nearly contemporaneous, exhibit a similar scene,—St. Bernard founding his abbey of Clairvaux in a place called the Valley of Wormwood, in the heart of a savage forest, the haunt of robbers, and his thirteen companions clearing a homestead, raising a few huts, and living on barley or cockle bread with boiled beech leaves for vegetables [Note 19].

How beautiful is Simeon of Durham's account of Easterwine, the first abbot after Bennet of St. Peter's at Wearmouth! He was a man of noble birth, who gave himself to religion, and died young. "Though he had been in the service of King Egfrid," says Simeon, "when he had once left secular affairs, and lain aside his arms, and taken on him the spiritual warfare instead, he was nothing but the humble monk, just like any of his brethren, winnowing with them with great joy, milking the ewes and cows, and in the bakehouse, the garden, the kitchen, and all house duties, cheerful and obedient. And, when he received the name of Abbot, still he was in spirit just what he was before to every one, gentle, affable, and kind; or, if any fault had been committed, correcting it indeed by the Rule, but still so winning the offender by his unaffected earnest manner, that he had no wish ever to repeat the offence, or to dim the brightness of that most clear countenance with the cloud of his transgression. And often going here and there on business of the monastery, when he found his brothers at work, he would at once take part in it, guiding the plough, or shaping the iron, or taking the winnowing fan, or the like. He was young and strong, with a sweet voice, a cheerful temper, a liberal heart and a handsome countenance. He partook of the same food as his brethren, and under the same roof. He slept in {404} the common dormitory, as before he was abbot, and he continued to do so for the first two days of his illness, when death had now seized him, as he knew full well. But for the last five days he betook himself to a more retired dwelling; and then, coming out into the open air and sitting down, and calling for all his brethren, after the manner of his tender nature, he gave his weeping monks the kiss of peace, and died at night while they were singing lauds." [Note 20]

9.

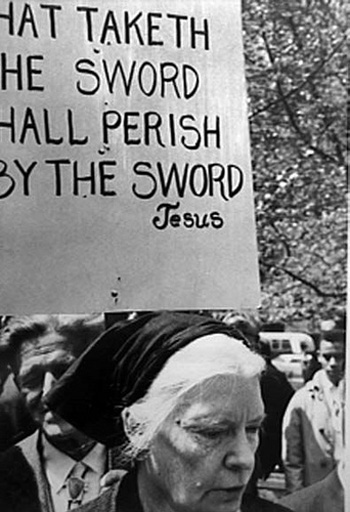

This gentleness and tenderness of heart seems to have been as characteristic of the monks as their simplicity; and if there are some Saints among them, who on the public stage of history do not show it, it was because they were called out of their convents for some special purpose, and, as I have said above, exceptions to a rule are commonly great exceptions. Bede goes out of his way to observe of King Ethelbert, on St. Austin's converting him, that "he had learned from the teachers and authors of his salvation that men were to be drawn heaven-wards, and not forced." Aldhelm, when a council had been held about the perverse opinions of the British Christians, seconding the principle which the Fathers of it laid down, that "schismatics were to be convinced, not compelled," wrote a book upon their error and converted many of them. Wolstan, when the civil power failed in its attempts to stop the slave trade of the Bristol people, succeeded by his persevering preaching. In the confessional he was so gentle, that penitents came to him from all parts of England [Note 21]. This has been the spirit of the monks from the first; the student {405} of ecclesiastical history may recollect a certain passage in St. Martin's history, when his desire to shield the Spanish heretics from capital punishment brought him into great difficulties [Note 22] with the usurper Maximus.

Works of penance indeed and works of mercy have gone hand in hand in the history of the monks; from the Solitaries in Egypt down to the Trappists of this day, it is one of the points in which the unity of the monastic idea shows itself. They have ever toiled for others, while they toiled for themselves; nor for posterity only, but for their poor neighbours, and for travellers who came to them. St. Augustine tells us that the monks of Egypt and of the East made so much by manual labour as to be able to freight vessels with provisions for impoverished districts. Theodoret speaks of a certain five thousand of them, who by their labour supported, besides themselves, innumerable poor and strangers. Sozomen speaks of the monk Zeno, who, though a hundred years old, and the bishop of a rich Church, worked for the poor as well as for himself. Corbinian in a subsequent century surrounded his German Church with fruit trees and vines, and sustained the poor with the produce. The monks of St. Gall, already mentioned, gardened, planted, fished, and thus secured the means of relieving the poor and entertaining strangers. "Monasteries," says Neander, "were seats for the promotion of various trades, arts, and sciences. The gains accruing from their combined labour were employed for the relief of the distressed. In great famines, thousands were rescued from starvation." [Note 23] In a scarcity at the beginning of the twelfth century, a monastery in the neighbourhood of Cologne distributed {406} in one day fifteen hundred alms, consisting of bread, meat, and vegetables. About the same time St. Bernard founded his monastery of Citeaux, which, though situated in the waste district described above, was able at length to sustain two thousand poor for months, besides extraordinary alms bestowed on others. The monks offered their simple hospitality, uninviting as it might be, to high as well as low; and to those who scorned their fare, they at least could offer a refuge in misfortune or danger, or after casualties.

Duke William, ancestor of the Conqueror, was hunting in the woods about Jumieges, when he fell in with a rude hermitage [Note 24]. Two monks had made their way through the forest, and with immense labour had rooted up some trees, levelled the ground, raised some crops, and put together their hut. William heard their story, not perhaps in the best humour, and flung aside in contempt the barley bread and water which they offered him. Presently he was brought back wounded and insensible: he had got the worst in an encounter with a boar. On coming to himself, he accepted the hospitality which he had refused at first, and built for them a monastery. Doubtless he had looked on them as trespassers or squatters on his domain, though with a religious character and object. The Norman princes were as good friends to the wild beasts as the monks were enemies: a charter still exists of the Conqueror, granted to the abbey of Caen [Note 25], in which he stipulates that its inmates should not turn the woods into tillage, and reserves the game for himself.

Contrast with this savage retreat and its rude hospitality the different, though equally Benedictine picture of {407} the sacred grove of Subiaco, and the spiritual entertainment which it ministers to all comers, as given in the late pilgrimage of Bishop Ullathorne: "The trees," he says, "which form the venerable grove, are very old, but their old age is vigorous and healthy. Their great grey roots expose themselves to view with all manner of curling lines and wrinkles on them, and the rough stems bend and twine about with the vigour and ease of gigantic pythons ... Of how many holy solitaries have these trees witnessed the meditations! And then they have seen beneath their quiet boughs the irruption of mailed men, tormented by the thirst of plunder and the passion of blood, which even a sanctuary held so sacred could not stay. And then they have witnessed, for twelve centuries and more, the greatest of the Popes, the Gregories, the Leos, the Innocents, and the Piuses, coming one after another to refresh themselves from their labours in a solitude which is steeped with the inspirations and redolent with the holiness of St. Benedict." [Note 26]

What congenial subjects for his verse would the sweetest of all poets have found in scenes and histories such as the foregoing, he who in his Georgics has shown such love of a country life and country occupations, and of the themes and trains of thought which rise out of the country! Would that Christianity had a Virgil to describe the old monks at their rural labours, as it has had a Sacchi or a Domenichino to paint them! How would he have been able to set forth the adventures and the hardships of the missionary husbandmen, who sang of the Scythian winter, and the murrain of the cattle, the stag of Sylvia, and the forest home of Evander! How could he have pourtrayed St. Paulinus or St. Serenus in his garden, who could draw so beautiful a picture of the old {408} Corycian, raising amid the thicket his scanty pot-herbs upon the nook of land, which was "not good for tillage, nor for pasture, nor for vines!" How could he have brought out the poetry of those simple labourers, who has told us of that old man's flowers and fruits, and of the satisfaction, as a king's, which he felt in those innocent riches! He who had so huge a dislike of cities, and great houses, and high society, and sumptuous banquets, and the canvass for office, and the hard law, and the noisy lawyer, and the statesman's harangue,—he who thought the country proprietor as even too blessed, did he but know his blessedness, and who loved the valley, winding stream, and wood, and the hidden life which they offer, and the deep lessons which they whisper,—how could he have illustrated that wonderful union, of prayer, penance, toil, and literary work, the true "otium cum dignitate," a fruitful leisure and a meek-hearted dignity, which is exemplified in the Benedictine! That ethereal fire which enabled the Prince of Latin poets to take up the Sibyl's strain, and to adumbrate the glories of a supernatural future,—that serene philosophy, which has strewn his poems with sentiments which come home to the heart,—that intimate sympathy with the sorrows of human kind and with the action and passion of human nature,—how well would they have served to illustrate the patriarchal history and office of the monks in the broad German countries, or the deeds, the words, and the visions of a St. Odilo or a St. Aelred!