H. R. H. Princess Ileana of Romania was born in Bucharest on January 7, 1909, the youngest daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Marie. She is a great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and also of Czar Alexander II of Russia, who freed the serfs. In 1931 she married Archduke Anton of Austria, and is the mother of six children.

A young girl during the First World War, the Princess saw suffering at first hand, grew up with a deep concern for the welfare of the people, became a Red Cross nurse in the last war when she set up and supervised her own hospital in Romania. In 1950, after her exile from her own country and two years in South America, she came to the United States. She has lectured extensively in this country and is the author of two books: I LIVE AGAIN, her memoirs, and a forthcoming volume, THE HOSPITAL OF THE QUEEN'S HEART.

She became an Orthodox nun in the 1960's and, as Mother Alexandra, became Abbess of the Transfiguration Monastery in Portland, Pennsylvania, and died in 1991.

HAVING been baptized into and brought up in the Eastern Orthodox Church, I have taken it for granted all my life. It is only lately that I was confronted with the question: "What is Orthodoxy? What do the Orthodox believe?" I have found myself being looked at and questioned with the misgiving and curiosity shown some exotic creature, not quite the same as other people.

I have not been offended by this curiosity; instead I have become equally curious to find out why so little is known about my Church which represents a greater part of Eastern Europe and a good part of Western Asia, as well as a significant number of Americans. I have found it imperative to seek out the truths in the churches of the East and West, and see for myself where the difference lies, and why they have grown such strangers to each other.

The Orthodox Church goes back to the very beginning of Christianity, evolving according to the needs and mentality of the peoples it united within its fold. At first, there was no Eastern or Western Church, but only one Catholic (universal and complete) and Orthodox (right-thinking) Church, which, as a body, kept the faith pure, and defended Christendom as a whole from heresies.

Arianism was condemned in the first of the seven Ecumenical Councils, held at Nicaea in 325. This Council was attended by 318 bishops from all parts of the then Christian world. The first seven articles of the Nicene Creed were formed at this time, and twenty canons were passed governing the rights and conduct of bishops and metropolitans. The last five articles of the Creed were formed at the second Council in the year 381 in Constantinople. This Council consisted of 150 bishops, all from the Eastern part of Europe; nonetheless, its decisions were fully accepted by the Western bishops. The other five councils of the undivided Church dealt with further heresies, and their rulings were accepted by East and West alike.

In the first centuries, there were five great Patriarchates—Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch, Rome and Constantinople. By degrees, two of them became the more important: Rome, because it was the imperial city and because its patriarch claimed direct apostolic descent from St. Peter, and Constantinople, which under the Emperor Constantine, became the new imperial city, the seat of government for the Roman Empire. When the Emperor left Rome for Constantinople, his authority gradually passed to the Bishop of Rome, who now alone stood for order and tradition in the western part of the empire abandoned to the barbarians from the North. Constantinople, meanwhile, quite naturally became the great center of the East. These two great Sees were in perfect accord in the fighting down of heresies and in compiling the Nicene Creed, to which to this day both firmly adhere, as they do to the apostolic hierarchy and all major dogmas of faith. Their estrangement came from political rather than from dogmatic differences, though these were later used as arguments. The most important of the dogmatic discussions centered around the Filioque in the Creed. (The Western Church says: "We believe in the Holy Ghost who proceeds from the Father and the Son . . .", while the Eastern Church says: ". . . proceeds from the Father, and is worshipped with the Father and the Son.")

The schism did not come about suddenly or with especial violence, although there was much regrettable and unChristian behavior on both sides. In fact, no one can actually put a date to the schism. Some place it in 1054; others 400 years later in 1439, after the abortive conference of Florence. It is perhaps one of the major catastrophes of Christianity that East and West fell apart. The advance of the great Moslem empire was partly responsible for this. For nearly 500 years it claimed Eastern Europe for its own, engulfing millions of souls and parting them effectively from their Western brothers.

This is a very brief outline of the historical facts. But the explanation of the breach is not to be found in history alone. Its causes lie much deeper, in the nature and mentality of East and West, and in the different interpretations each gave the same belief and creed.

It can never be sufficiently stressed that there never was disagreement on a point of faith; that neither Orthodox nor Roman Catholics considered the others heretics, but rather schismatics. A grave sin which each regrets to have seen the other fall into! Alas for Christianity, this sin was committed, and the great spiritual power of unity has been lost! Yet who can penetrate the ways and will of God, and why did each branch have to work out its separate way to salvation? Each accumulated its wisdom and knowledge according to the minds of different peoples; each became rich in a spirituality that goes deep into the nature of things, so that today both sides have stored great treasures, which, if joined together, may yet bring the world more peace and joy than we understand or can imagine.

We are now living in a time when cultures are being brought close together, meeting and interchanging thoughts and ideas. By the migration of people, through wars and oppression, the Eastern Church has moved westward and is mingling with churches of all denominations. No more are Orthodox Churches in America and Europe just chapels serving small groups of Russians, Serbs, Greeks, Romanians, and others; they have become a part of American life. Nearly five million Americans now belong to this confession, which has its own churches, schools and seminaries. Orthodoxy is no longer a vague and distant faith of Oriental peoples, but is an integral part of American life today. What, then, does it stand for?

It stands for Christianity unimpaired, and transmitted unchanged to us through the Church's Holy Tradition. It teaches that there is only one church, and that that church is Orthodox and Catholic. It is believed to be firmly based upon the teachings of our Lord as transmitted by the first Apostles and through the Gospel. Because the creeds and even the Holy Scriptures came into being after the founding of the Church by Christ and the Apostles, "Holy Tradition" is venerated in the Church. Notwithstanding the fact that after the destruction of the Byzantine Empire, the Eastern Church fell into various national groups, the Tradition has remained unimpaired. Through hundreds of years of Ottoman and other persecution, the heads of the churches could meet but seldom to discuss points of dogma, yet all have kept the same exact faith and, although each group necessarily reads the Liturgy in its own tongue, the ceremony varies only slightly if at all.

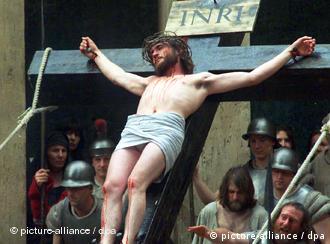

This brings us to the importance of the Liturgy which is the whole life of the Church. Liturgy is the Eastern word for Mass or Eucharist. The rite focuses upon worship and it combines both praise and thanksgiving for our Lord's self-sacrifice. It depicts in various symbols the entire life of our Lord from birth to crucifixion and glorious resurrection. There is an intimacy in the relationship of the faithful and clergy and in the participation of all in the service, which is not apparent nor easily understandable to those accustomed to Western services. Although partaking of Holy Communion is not as frequent as in the Western Church, the congregation always takes a very real and spiritually active part in offering the Eucharistic sacrifice. The pomp and ceremony, the mystery, the closed altar doors, the glory of the hymns—far from intimidating and estranging the faithful, all these make them part of the Sacrament. The beauty, the music, the prayers, detach them from their mundane life; their intellect can be at peace. Because of this powerful mystical participation of all in the Liturgy the Orthodox confession is the same church, with the same ceremony, the same expression the world over, regardless of race, nationality or language.

The next important point is the extreme reverence given the Holy Scriptures. Both the Old and the New Testaments figure largely in the Orthodox daily life. Not only has their study been encouraged from earliest times, but even the illiterate have learned whole portions by heart. The Psalms are part of everyday prayers. The simplest peasant in the most isolated mountain valley in the Carpathians, Balkans or Caucasus is able to cite a Bible verse applicable to any situation in which he may find himself.

Because the Ottoman sovereignty over the Christian peoples of the East was expressed in both religious and national persecution, it followed quite naturally that faith and nationalism should become one and the same thing. Thus people and Church were in very truth united. National kings were anointed by the Church and were part of that Church. This union of Church and State, however, was not always an advantage, but the pros and cons of this point are too lengthy and weighty to be discussed adequately in this short account of Orthodoxy. The important thing is that Orthodoxy has survived Ottoman persecution, Czarism, and is even now surviving Communism. Although the various national groupings are at present a hindrance to concentrated Orthodox action, they have not impaired the Orthodox faith, and no member of any one group seeking the ministrations of the Church is out of communion with any other group. He can freely participate in the Holy Mysteries wherever he finds them.

The Orthodox Church does not speak of Sacraments, but of Holy Mysteries. It does not try to put them into cut-and-dried formulae but accepts them with gratitude and awe. The Easterner has a less inquisitive mind than the Westerner; his mind is more contemplative, less disciplined, but profounder than the Western mind. Where the latter wants definitions, clear intellectual understanding and perception, the former will seek the depths and is content with undefined contacts with the intangible. Perhaps because of long persecutions, he has been thrown more upon himself, and has had to go deeper into reality by himself. There has been less definition and therefore less divergency of opinion. When there have been revelations, their authenticity has not been judged by schooled contemporary minds, but has been held up for judgment by the Church's tradition. If such revelation was found to be in accord with that tradition, it was accepted. The Orthodox Church has been less eager than the Western churches to move with the times, for it feels that it holds the eternal verities. At the same time, it has remarkable adaptability and independence of movement with which to break with any custom when circumstances demand. For example, when Communist Serbia declared Christmas Day a working day so that church services could not be attended, Liturgies were read from midnight on, every two hours until morning, despite the fact that tradition long has ruled that only one Mass in twenty-four hours was to be said at the same altar. Yet, no individual feels that any authority can give him dispensation from the Church's traditional rules, such as that of fasting, which, for the Orthodox, is extremely severe. He feels that the Church's rules were divinely inspired when the Church was founded and no human has either the power or the right to change them or to add to them.

It is a very important factor in the discipline of the Orthodox Church, and largely constitutes its surviving power, that its principles are so deeply ingrained in the laity that the law of the Church is often stronger in them than in the clergy. For example, the laity will accept the Synod's decisions concerning recognition of other confessions, orders and communions with which it feels not competent to deal, but would never accept new dogmas or the doing away with old ones. And no Orthodox would conceive of changing religion for family reasons or because of a change of community, though we would be very tolerant of a change made from spiritual conviction.

There is a belief that, as the Western Church was founded by St. Peter and St. Paul, so the Eastern Church was founded by St. John. Be this as it may, there is no doubt that the Orthodox Church is greatly influenced by the Gospel and Epistles and the Revelations of St. John, and that of these, the spirituality and beauty of the fourth Gospel is its leading factor. The very term "Mystery" for "Sacrament" comes from St. John. An example of the Church's attitude is in the passage in St. John 3:1-21 which tells of our Lord's discussion of the spiritual rebirth of man with Nicodemus; even after Jesus' explanation Nicodemus does not understand. Jesus says: "Art thou a master of Israel and knowest not these things?" and then goes on to explain at length His nature and the way to salvation. The Orthodox Christian does not question but believes in the rebirth of man through the Holy Mysteries which the Church has guarded for him direct from our Lord.

These Holy Mysteries or Sacraments are seven in number—Baptism, Chrismation (equivalent to Western Confirmation), Communion, Penance, Holy Orders, Matrimony and Unction. Let us go over these seven Mysteries and explain the Orthodox catechism, known as "The Faith of the Saints."

A Holy Mystery or Sacrament "is a visible ritual performance through which the invisible saving power called God's grace bestows wonderful gifts upon the recipients."1

Since the word "grace" is so often misunderstood, I believe it is well before going further, to declare the Orthodox definition of the word: "God's grace is God's gift which the Father gives men through the Holy Spirit because of the merits of the Son."2

Baptism is the first Holy Mystery, and by it the baptized person is cleansed of all sin, original and personal, and as a newborn child of God, is incorporated into the Church of Christ.

This ceremony is performed by thrice-repeated total immersion in water, in the name of the Holy Trinity—of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Ghost. The three immersions represent death to sin against the Trinity, and the three risings mean the life in and to the Holy Trinity. The Church's authority for baptism comes direct from Christ, in His clear commandment to His disciples to teach and baptize all nations (Matt. 28:19), and also His stern warning: "Except a man be born of water and of the spirit, he cannot enter the Kingdom of God." (John 3:5). (To the Orthodox, the death of an unbaptized child means its eventual exclusion from the Christian family on the day of the Last Judgment.) Baptism is also a sign of obedience to the Apostolic practice (Acts 10:44-48, 16:15 and I Cor. 1:16). Above all, it is right because of the love of Jesus who commanded: "Let the children come unto Me," and what Christian would not harken to this call?

Baptism is followed immediately by the Holy Chrismation, the second Holy Mystery, through which a baptized person is armed with strength and wisdom by the Holy Spirit. The priest anoints the forehead, breast, eyes, ears, cheeks, mouth, hands and feet with the Holy Chrism (oil) pronouncing the words: "The seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit. Amen." These words are taken from II Cor. 1:21-22: "He who establisheth us with you in Christ, has anointed us in God who has also sealed us, and given us the earnest of the spirit in our hearts."

Chrismation is an extension of, and a sharing in the unction of our Lord with the Holy Ghost, accomplished by the Father. Therefore, the unction unites us not only to the Spirit, but to the Son.3

The holy oil is prepared and consecrated by the bishops, and its use is thus an equivalent to the laying-on of hands in Confirmation in the Western churches, the transmitting of the Holy Ghost. The Orthodox Church offers no theory about the manner of this transmission, but remembers "that God is a Spirit and must be worshipped in spirit and in truth (John 4:14), especially when we turn to the Person of the Holy Ghost." The Chrism is but the channel "of the invisible and spiritual unction which God pours into the hearts of men whenever and wherever He pleases."4

St. Paul says: "The foundation of God standeth sure, having this seal, the Lord knoweth them that are His." (II Timothy 2:19). The Book of Revelation enumerates the servants of God "sealed" from all tribes. (Rev. 7:3-4).

St. Cyril of Jerusalem puts it this way: "Do not forget the Holy Ghost at the time of your illumination; He is ready to stamp your soul with His seal."

A monk of the Eastern Church writes: "The sealing by the Holy Ghost means therefore that the Spirit imprints on us the Father's likeness; that is, the Lord Jesus Himself. From that moment we do not belong any more to ourselves. We have become . . . the slaves and the soldiers of Christ and His sacrificial co-victims. The first Christians used the expression "to keep the seal" in the sense of remaining faithful."5

Once the new Christian has received the Holy Mysteries of Baptism and Chrismation, he is ready to accept the Holy Eucharist. The first two ceremonies are performed in the transcept of the church. Now the child is brought up to the altar by his godparent. He will now partake, as all faithful Christians do, of the true Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ in the visible form of bread and wine. From now on, this will be the central part of his spiritual life. Although there is no ruling about this, a child, after the first communion following his baptism, usually does not communicate until he is able to do so intelligently—around the age of seven, unless he is mortally ill.

Holy Communion, or the Eucharist, is the center of all Orthodox worship, and is prepared and used in the Divine Liturgy. "The aim of man's life is union with God and deification."6 Deification is not, of course, "a pantheistic identity, but is a sharing through grace of the divine life."7

"This participation takes man within the life of the three Divine Persons themselves, in the incessant circulation and overflowing of love which courses between the Father, the Son and the Spirit, and which expresses the very nature of God. . . . Union with God is the perfect fulfillment with the Kingdom, announced by the Gospel, and that love which sums up all the Law and the Prophets."8

The faithful seek this union through communion. "The Orthodox Church . . . believes that the Sacraments are not mere symbols of divine things, but that the gift of spiritual reality is attached to these signs perceptible by the senses . . . that is, in the Eucharistic mystery, the same grace is present nowadays that was once imparted in the Upper Room. There are two aspects to this: the mystical and the aesthetical. The mystical aspect consists in the fact that Sacramental grace is not the outcome of human effort but is bestowed objectively by our Lord. The aesthetical aspect consists in the fact that the Holy Mysteries bring forth their fruit in the . . . recipient only if that soul is assenting to, and is prepared for it. The Greek Fathers emphasized human freedom in the work of salvation."9 St. John Chrysostom writes: "We must first select good and then God adds what appertains to this office. He does not act antecedently to our will, so as not to destroy our liberty."10

"Clement of Alexandria coined the word "synergy" (cooperation) in order to express the action of these two co-joined energies: grace and human will. This term and idea . . . represents today the doctrine of the Orthodox Church on these matters."11 For this reason, the faithful feel that their active part in the Liturgy is essential, and preparation for making their communion is taken very seriously, preceded always by a day of fasting and by confession.

"Orthodoxy does not agree with the Latin doctrine of Transubstantiation, but believes that Christ who is offered in the mystery of the Holy Supper, is truly there present . . . Orthodoxy does not practice the cult of the consecrated elements outside the Liturgy."12 The Roman Church further makes a great point of difference in the actual moment that the mystery takes place. They fix it at the use by the priest of the words of Institution: "This is My Body . . . This is My Blood."—while the Orthodox say that "the sanctification of the Holy Gifts operates during the entire Liturgy, whose essential part consists in the words of institution of Our Lord following the invocation of the Holy Spirit, and the benediction of the elements ("epiklesis").13

Eucharistic grace fulfills the grace of Baptism and of Chrismation. In the Paschal mystery is found the Lord's Supper, the Passion and the Resurrection, yet the Eucharistic Sacrament is not an end in itself, but a means to spiritual reality greater than the sacraments themselves. Communicating with Christ, we communicate with all His members. "For we being many, are one bread and one body: for we are partakers of that one bread." The Eucharist is the life flow that courses through the whole body of Christ's Church. We do not absorb it; it absorbs us.

For man to be worthy of so great a love by which God gave His only begotten Son to save us from sin and perdition is almost superhuman. It could not be, had not our Lord instituted also the Mystery of Holy Penance when He told us to confess our sins to each other and gave His Apostles the power to remit sins. "Receive ye the Holy Spirit; whosoever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them, and whosoever sins ye retain, they are retained." (John 20:22-23)

Every sin we commit against man, we commit against God, too. There is no sin that does not hurt God. It is not sufficient to confess and make retribution to the person injured, but we should seek also to confess to a priest, successor to the Holy Apostles, who have spiritually inherited the power to forgive sins. There are sins for which there appears, to human understanding, to be no forgiveness. Yet we know of many instances of great sinners who, through true repentance had their sins remitted, and have become great saints.

The Church urges frequent confession, especially before Holy Communion and during illness, so that the soul may ever be ready to stand before the Judgment Seat. In no way is this a control of the faithful's lives by the priesthood. The priest is only the channel through which men gain God's forgiveness. One does not confess to the priest as a person, but to God through the priest. The priest is there to help the penitent formulate his sin and to be the visible transmitter of God's grace of forgiveness. He is the vehicle which Christ instituted for this purpose.

Here, as in all the other Mysteries, the Orthodox Church teaches that "God is not bound to the Sacraments; there is 'One greater than the Temple' (Matt. 12:6) and greater than the Holy Mysteries."14 That is to say, that should death befall a person where he cannot partake of any of the Mysteries, God may yet reach him if his soul is prepared by love and repentance. "Unsearchable are His judgments and His ways past finding out." (Rom. 11:33) When He so wishes it, God does not need the visible ritual performance to bestow His gifts.

The Orthodox Church does not have the dogma of Purgatory. "According to the Orthodox Church, death ends man's probation and immediately after death he is judged. His fate in eternity is determined by his whole moral state at the moment of death."15 "We believe that the souls of the departed are in repose or torment as each one wrought, for immediately after the separation from the body, they are pronounced either for bliss or for suffering and sorrow, yet we confess that neither the joy nor the condemnation are as yet complete. After the general resurrection, when the soul is united to the body, each one will receive the full measure of joy or condemnation due to him for the way in which he conducted himself, whether well or ill." (Confessions of Dositheus at the Synod of Constantinople, 1672) .

The Orthodox Church makes no hard and fast pronouncement, any more than do the Gospels, as to what the state of the soul is, and where it resides between death and the day of Judgment. We know there is a Heaven and a Hell, and that they are a state of the spirit. "Neither shall they say lo here! or lo there! for behold, the Kingdom of God is within you." (Luke 17:21). Our Lord also said: "In My Father's house there are many mansions; if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you." (John 14:2).

We also firmly believe that man's probation and his free choice are here on earth, and that "Christ's power to forgive sins is on this side of the grave", as Theophylact says in St. Luke 5:24, commenting on the words of Christ (when He says "that the Son of man hath power on earth to forgive sins"). Notice that it is on earth that sins are forgiven. So long as we are on earth, we can blot out our sins; after we have departed from the earth, we are no longer able to blot them out by confession, for the door is shut!16 Androutsos has said: "The absolution is a full, complete, and entire forgiveness and remission of all sin and a restoration and return to the state of grace."17 Furthermore, the idea of the necessity of propitiating the Divine righteousness by means of penalty is foreign to the Orthodox conception of an all loving and just God, limiting His powers.

Certain grievous sins are unforgivable, not as from the powerlessness of God or the Church, but because by their nature they make those committing them unrepentant and callous, so that in such cases divine Grace cannot operate. (Androutsos. Gavin p. 360)

The fifth Holy Mystery is Holy Orders. It is the mystery by which the Holy Spirit, through the laying-on of hands of bishops, gives grace and authority to the newly ordained priest or bishop to perform the Mysteries, and to conduct the religious life of the people. Through the touch of consecrated hands, this spiritual power is communicated to the person ordained, and thus the lawful continuity, authority and ministry of the Church was and is secured. (I Timothy 4:14 and 5:22).

Bishops have this grace because they are the successors of the Apostles. Christ Himself is our High Priest. (Heb. 5:4-6). He is the source of all power and authority in His Church, and gave the power to the Apostles to teach, to heal, and to forgive the sins of men.

There are three degrees of Holy Orders: bishops, priests and deacons. A bishop can administer all seven mysteries: the priest, all except Holy Orders: and the deacon assists both the bishop and the priest, but by himself, cannot perform any of the Sacraments.

A word should be inserted here about the monastic orders in the Orthodox Church. There are no differing orders in the sense that the Western Church uses the term, that is to say Franciscans, Benedictines, etc. There is a very strong monastic tradition in the Eastern Church. Since the time of St. Anthony of Egypt all the monasteries and convents follow the prescriptions of St. Basil the Great. Their chief objective is contemplative prayer. There is no set rule of probation or novitiate as in the West. There are three grades of monks: The lowest (Greek: rasophore, Slavic: rejasonosts) may be entered very shortly after the aspirant comes into the monastery. The second (Greek: stavrophore, Slavic: skhimnik) can be entered after three years, and if the postulant is over 25 (and in the case of a woman over 40). They then take four oral vows—of poverty, obedience, chastity and stability. To reach the third degree, megaloskhomos, to which only a few attain, takes 20 to 30 years of preparation. These monks devote themselves entirely to contemplative prayer, becoming hermits and taking the vow of silence. This is the pinnacle for which they are trained during the years of discipline in the communal life of the first two degrees. Many never pass the first two degrees; nonetheless, all are monks; the degree is one of spiritual attainment. Not all monks are priests (hiermonk) and no distinction is made between them if they are. All Bishops have to be monks of the first or second degree. If a Bishop should attain to the third degree, he has to resign all episcopal and sacerdotal functions except the celebration of the Liturgy, because of the extremely penitential and strict discipline and the long periods of silence.

Many monasteries and convents devote themselves to the care of the sick and suffering and also education; but these are side activities. The reason for monastic life in the East is prayer and contemplation, the drawing of the soul ever closer to God.

The sixth Holy Mystery is that of Matrimony, which represents the union of two souls and two bodies, and sanctifies this union that they are no more two, but one body.

The seventh Holy Mystery is Holy Unction, which consists of the priest's prayers and the anointing of a sick person with blessed oil through which God's grace affects the recovery of the sufferer. By sickness is meant both that of body and soul, for Unction heals the body of its infirmities as it cleanses the soul of its sin. St. James advises: "Is any sick among you? Let him call for the Elders of the Church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord, and the prayer of faith shall raise him up; and if he has committed sins they shall be forgiven him." (James 5:14-15). In this, the priest follows the tradition of the Apostles who, directed by Christ Himself, preached the Gospel, and among other miracles they "anointed with oil many that were sick and healed them." (Mark 6:13). This mystery is not necessarily reserved for the dying, but is administered also to any sufferer.

Thus the Church presides over the mysteries of all needs of man through its hierarchy.

In the Apostles, Our Lord laid the foundation of the hierarchy: to deny this would be to oppose the will of the Lord. Of course, the Apostles, by their consecration did not become equal or like Our Lord, vicars of Christ, or substitutes for Christ . . . Our Lord Himself lives invisibly in the Church "always now and forever and to eternity"; the hierarchy of the Apostles did not receive power of place, but power to communicate the gifts necessary to the Church . . . to the hierarchy belongs the authority to be mediators, servants of Christ18 from whom they received full power of their ministry as such: "the hierarchy represented by the episcopate becomes a sort of external doctrinal authority which regulates and moralizes the dogmatic life of the Church. . . . Inasmuch as the Church is a unity of faith and beliefs, bound together by the hierarchic succession, it must have its doctrinal definitions supported by the whole power of the Church. In the process of determining these truths the episcopate gets together with the laity, and appears as representative of the laity."19 "With us, the guardian of piety is the very body of the Church, that is, the people themselves, who will always preserve their faith unchanged." (Epistle of the Eastern Patriachs, 1849). This gathering is called the Synod, and is the Church's supreme authority.

Every Christian receiving Baptism becomes part of the Church and is responsible as a member for guarding the faith and also spreading it abroad. When the Church is spoken of, the entire Church is meant—the hierarchy, the laity—the living and the departed.

"Here we touch the very essence of Orthodox doctrine of the Church. All the power of Orthodox ecclesiology is concentrated on this point. Without understanding the question, it is impossible to understand Orthodoxy; it becomes dynamic compromise, a middle way between Roman and Protestant viewpoints. The soul of Orthodoxy is sobernost—according to the perfect definition of Khomiakov; in this one word of his is contained a whole confession of faith. . . .20 It is a Slavonic term but used in many Orthodox churches even by those whose language is basically Latin as for instance in the Romanian. It is used in place of "Catholic" in the Creed "Cred intr' una Sfanta Soborniceasca si Apostolica Biserica" (I believe in one "sobornical" and Apostolic Church).

"What then is sobornost?"

The word is derived from the verb "sobirat" to reunite, to assemble. From this comes the word "sobor" which, by a remarkable coincidence means both "council" and "church". Sobornost is the state of being together. . . . To believe in a "sobornaia" church is to believe in a Catholic Church, in the original sense of that word, and in a church that assembles and unites—it is also to believe in a conciliar church. Orthodoxy, says Khomiakov, is opposed to both authoritarianism and to individualism; it is a unanimity, a synthesis of authority. It is the liberty in love which unites believers. In the word "sobornost" is expressed all that.21

When the Church speaks, it is this sobor which speaks through the ages from its very foundation. All new problems are judged by the judgment of the entire Church through the inspiration of the Holy Ghost. Thus "the Church is infallible, not because it expresses the Truth correctly, from the point of view of practical expediency, but because it contains the Truth. The Church, Truth, infallibility, these are synonyms."22

Another important element in the Orthodox faith is one without which its spiritual life would not be complete. This is the Communion of Saints, "which is a sharing of the prayers and good works of the heavenly and earthly Christians, and a familiar intercourse between ourselves and the glorified saints."23

The worship of saints must not be misunderstood or confused with the adoration due to God alone. It is, in fact, more correctly termed veneration. St. John Damascene says that veneration "is paid to all that are endowed with some dignity." But this relationship is not one of respect and honor to those who have lived good and saintly lives, but "just as a living Christian can beg the intercession of another living Christian, so we commend ourselves to the prayers of the saints."24

"The Orthodox Church gives a great place in its calendar to the patriarchs and prophets and to the just men of the Old Testament contrary to the practices of the Latin Church". Very high in the heavenly order stand the angels. The classification of angels and saints matters little; the important thing is that their recognition accords with the Scriptures. "The Greek Fathers lay particular stress upon our guardian angels . . . calling them pedagogues . . . fellow wayfarers . . . preceptors".25 Above all, they are according to the "Biblical conception of the divine messengers, the guides of men. They are the bearers of the very Name and Power of God. They are flashes of light and strength of the Almighty Lord; there is nothing rosy or weakly poetical about them. . . . An integral Christian life should imply a daily and familiar intercourse with the angelic world."26

The Church teaches that each man has a guardian angel who stands before the face of the Lord. This guardian angel is not only a friend and protector, who preserves from evil and who sends good thoughts: the image of God is reflected in creatures—angels and men—in such a way that angels are celestial prototypes of men; guardian angels are especially our kin.27

The Blessed Virgin Mary, mother of God Incarnate, is held in especially high veneration. She stands above all other saints "more honourable than the cherubim and incomparably more glorious than the seraphim". Since the Gospel is the first and main source of Orthodox piety this veneration has its chief origin in the following New Testament text: "Hail, thou that art highly favored, the Lord is with thee; blessed art thou amongst women . . ." (Luke 1:28 to 29), and her answer "Behold the handmaiden of the Lord: be it unto me according to Thy word." (Luke 1:38) The description of the wedding in Cana of Galilee (John 2:3-5) denotes a special relationship between Mother and Son. Again, in Luke 11:27-28 that short and often misinterpreted conversation between the Lord and a woman unknown: Blessed is the womb that bare thee . . ." But He said, "Yea, rather, blessed are they that hear the word of God and keep it," a declaration which does not disparage Mary, but points out where her true merit lies,28—namely, that she heard and accepted the word of God. Finally, there are the Lord's words to St. John at the Cross: "Behold thy mother," (John 19:26-27). The Church has a special period of fasting before the Assumption and numerous feasts and hymns dedicated to Mary. We venerate in her the sanctification and glorification of human nature, because through her as a perfect spotless vessel God became man—"The Church never separates Mother and Son, she who was incarnated by Him Who was Incarnate—In adoring the humanity of Christ, we venerate His Mother, from whom He received His humanity and who, in her person, represents the whole of humanity."29

I must dwell here for a little upon the icons which are such an integral part of Orthodoxy. The word icon is actually "image" yet it is not, as in the Latin Church, a resemblance. "The Orthodox Church keeps the precept of the Decalogue: Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image or likeness . . ." The icon is to be regarded rather as a sort of hieroglyph, a simplified symbol, a sign, an abstract scheme. The more an icon tends to reproduce human features, the further it swerves from the iconographical canons of the Church. "While the likeness is for the West a means of elevation and teaching, the Eastern icon is a means of communion. The icon is loaded with grace of an objective presence; it is a meeting place between the believer and the Heavenly world."30

The Orthodox Church also venerates the relics of saints "From the dogmatic point of view the veneration of relics (as well as that of the icons of Saints) is founded on faith in special connection between the spirit of the Saint and his human remains; a connection which death cannot destroy. In the case of Saints, the power of death is limited; their souls do not altogether leave their bodies, but remain present in spirit and in grace in their relics, even in the smallest portion. The relics are bodies already glorified in earnest of the resurrection although still awaiting that event. They have the same nature as that of the body of Christ in the Tomb, which, although it was awaiting its resurrection and dead, deserted by the soul, still was not altogether abandoned by His divine spirit."31

"Byzantine Art does not compete with color photography. Religious art is not concerned with pretty, proportioned figures of men and women, but with beauty of spirit, with self-sacrifice, with prayer, with service to God and fellowman, and above all, with the life hereafter. It takes conscious effort over an extended period of time to free oneself from the material world to contemplate the message of ancient icon painters; it is the message of the Church. . . . An icon aims at transfiguration of the human face and figure as it might be in the Kingdom of God. . . .

"Those who have bequeathed the riches of a unique religion to us did so out of love of fellowman and God. Our icons are not signed. We do not know who painted some of our greatest masterpieces. The artists' idea was to glorify the Heavens, not themselves. 'Blessed are the humble, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven'."32

"There is, in my opinion, a parallel between Orthodox art and Orthodox music. The spirit of namelessness, humility and above all the everlasting qualities in an icon are to be found in the traditional chants and great compositions sung in our churches. Without musical accompaniment, the interpretation and attitude of the singers becomes all-important. In this field, the Russians, who have the longest continuous history for free development of all Orthodox, have contributed much. Most of us who are Orthodox do not regard ourselves as theologians, but one element which particularly endears our religion to us, is the spiritual realm of music.

"There is a great affinity between the Eastern Orthodox Churches and the Anglican Church. Both are self-governing churches bound together by the same Eucharistic rite. Both of them are administered by a collaboration of the clergy and laity. Neither Church is bound to one school of thought which might hold it to a doctrinal system aimed at defining their logical-problems in a cut-and-dried way. Above all, they are both inspired by the same ideal of unity in freedom, an ideal which, if not always necessarily realized, is nonetheless faithfully and lovingly adhered to by both."33

The Anglican and the Orthodox Churches are admirably suited to start the healing of the breach which, for over six hundred years has separated the East from the West. Each has much to contribute to the other. The Orthodox has all the dogmatic and liturgical riches that the Anglican needs today. By entering into communion with the whole Orthodox Church, the Anglicans would strengthen their own Apostolic tradition. Their orders, recognized by all Orthodox Churches, would give them an unassailable position towards Rome, and at the same time they would be a bridgehead towards the Protestant Churches, by virtue of being both Catholic and Protestant.

There is a strong movement to seek understanding among the clergy of both confessions, but it is not sufficiently shared by the laity, who in both churches know practically nothing about each other. Yet, if this healing is to take place, all must participate in it, heart and soul and mind, becoming not only in theory, but in very fact, One Body in Christ Jesus. This, I realize, is a problem that can only be approached with much prayer, thought, devotion, and time.

This short, all-too-short and sketchy exposition of Orthodox thought and doctrine should end, as all things should, in prayer, and prayer is the Invocation of the Name of Jesus. In spite of the great pomp and ceremony of the Liturgy, this prayer is simple to a degree and opens the door to contemplation and to the at-one-ment of the soul with God; it is the apex towards which all other prayers tend. "The Invocation of the name of Jesus can be put into many strains. It is for each person to find the form which is the most appropriate to his own ear or prayer; but whatever formula may be used, the heart and center of this invocation must be the Holy Name itself; the word "Jesus". There resides the whole strength of the invocation.

The name of Jesus may either be used alone or be inserted in the more or less developed phrases. . . . "The name of Jesus only is the most ancient mold of the invocation of the Name."35

Until the whole person, mind, soul and body can lose itself and at the same time comprehend the allness of God in one word, let us learn in all honesty to say: "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me, a sinner."

H. R. H. Princess Ileana of Romania was born in Bucharest on January 7, 1909, the youngest daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Marie. She is a great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and also of Czar Alexander II of Russia, who freed the serfs. In 1931 she married Archduke Anton of Austria, and is the mother of six children.

A young girl during the First World War, the Princess saw suffering at first hand, grew up with a deep concern for the welfare of the people, became a Red Cross nurse in the last war when she set up and supervised her own hospital in Romania. In 1950, after her exile from her own country and two years in South America, she came to the United States. She has lectured extensively in this country and is the author of two books: I LIVE AGAIN, her memoirs, and a forthcoming volume, THE HOSPITAL OF THE QUEEN'S HEART.

Additional copies may be obtained from

THE ADVENT PAPERS

135 MOUNT VERNON STREET

BOSTON 8, MASSACHUSETTS

The Spirit of Orthodoxy

HAVING been baptized into and brought up in the Eastern Orthodox Church, I have taken it for granted all my life. It is only lately that I was confronted with the question: "What is Orthodoxy? What do the Orthodox believe?" I have found myself being looked at and questioned with the misgiving and curiosity shown some exotic creature, not quite the same as other people.

I have not been offended by this curiosity; instead I have become equally curious to find out why so little is known about my Church which represents a greater part of Eastern Europe and a good part of Western Asia, as well as a significant number of Americans. I have found it imperative to seek out the truths in the churches of the East and West, and see for myself where the difference lies, and why they have grown such strangers to each other.

The Orthodox Church goes back to the very beginning of Christianity, evolving according to the needs and mentality of the peoples it united within its fold. At first, there was no Eastern or Western Church, but only one Catholic (universal and complete) and Orthodox (right-thinking) Church, which, as a body, kept the faith pure, and defended Christendom as a whole from heresies.

Arianism was condemned in the first of the seven Ecumenical Councils, held at Nicaea in 325. This Council was attended by 318 bishops from all parts of the then Christian world. The first seven articles of the Nicene Creed were formed at this time, and twenty canons were passed governing the rights and conduct of bishops and metropolitans. The last five articles of the Creed were formed at the second Council in the year 381 in Constantinople. This Council consisted of 150 bishops, all from the Eastern part of Europe; nonetheless, its decisions were fully accepted by the Western bishops. The other five councils of the undivided Church dealt with further heresies, and their rulings were accepted by East and West alike.

In the first centuries, there were five great Patriarchates—Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch, Rome and Constantinople. By degrees, two of them became the more important: Rome, because it was the imperial city and because its patriarch claimed direct apostolic descent from St. Peter, and Constantinople, which under the Emperor Constantine, became the new imperial city, the seat of government for the Roman Empire. When the Emperor left Rome for Constantinople, his authority gradually passed to the Bishop of Rome, who now alone stood for order and tradition in the western part of the empire abandoned to the barbarians from the North. Constantinople, meanwhile, quite naturally became the great center of the East. These two great Sees were in perfect accord in the fighting down of heresies and in compiling the Nicene Creed, to which to this day both firmly adhere, as they do to the apostolic hierarchy and all major dogmas of faith. Their estrangement came from political rather than from dogmatic differences, though these were later used as arguments. The most important of the dogmatic discussions centered around the Filioque in the Creed. (The Western Church says: "We believe in the Holy Ghost who proceeds from the Father and the Son . . .", while the Eastern Church says: ". . . proceeds from the Father, and is worshipped with the Father and the Son.")

The schism did not come about suddenly or with especial violence, although there was much regrettable and unChristian behavior on both sides. In fact, no one can actually put a date to the schism. Some place it in 1054; others 400 years later in 1439, after the abortive conference of Florence. It is perhaps one of the major catastrophes of Christianity that East and West fell apart. The advance of the great Moslem empire was partly responsible for this. For nearly 500 years it claimed Eastern Europe for its own, engulfing millions of souls and parting them effectively from their Western brothers.

This is a very brief outline of the historical facts. But the explanation of the breach is not to be found in history alone. Its causes lie much deeper, in the nature and mentality of East and West, and in the different interpretations each gave the same belief and creed.

It can never be sufficiently stressed that there never was disagreement on a point of faith; that neither Orthodox nor Roman Catholics considered the others heretics, but rather schismatics. A grave sin which each regrets to have seen the other fall into! Alas for Christianity, this sin was committed, and the great spiritual power of unity has been lost! Yet who can penetrate the ways and will of God, and why did each branch have to work out its separate way to salvation? Each accumulated its wisdom and knowledge according to the minds of different peoples; each became rich in a spirituality that goes deep into the nature of things, so that today both sides have stored great treasures, which, if joined together, may yet bring the world more peace and joy than we understand or can imagine.

We are now living in a time when cultures are being brought close together, meeting and interchanging thoughts and ideas. By the migration of people, through wars and oppression, the Eastern Church has moved westward and is mingling with churches of all denominations. No more are Orthodox Churches in America and Europe just chapels serving small groups of Russians, Serbs, Greeks, Romanians, and others; they have become a part of American life. Nearly five million Americans now belong to this confession, which has its own churches, schools and seminaries. Orthodoxy is no longer a vague and distant faith of Oriental peoples, but is an integral part of American life today. What, then, does it stand for?

It stands for Christianity unimpaired, and transmitted unchanged to us through the Church's Holy Tradition. It teaches that there is only one church, and that that church is Orthodox and Catholic. It is believed to be firmly based upon the teachings of our Lord as transmitted by the first Apostles and through the Gospel. Because the creeds and even the Holy Scriptures came into being after the founding of the Church by Christ and the Apostles, "Holy Tradition" is venerated in the Church. Notwithstanding the fact that after the destruction of the Byzantine Empire, the Eastern Church fell into various national groups, the Tradition has remained unimpaired. Through hundreds of years of Ottoman and other persecution, the heads of the churches could meet but seldom to discuss points of dogma, yet all have kept the same exact faith and, although each group necessarily reads the Liturgy in its own tongue, the ceremony varies only slightly if at all.

This brings us to the importance of the Liturgy which is the whole life of the Church. Liturgy is the Eastern word for Mass or Eucharist. The rite focuses upon worship and it combines both praise and thanksgiving for our Lord's self-sacrifice. It depicts in various symbols the entire life of our Lord from birth to crucifixion and glorious resurrection. There is an intimacy in the relationship of the faithful and clergy and in the participation of all in the service, which is not apparent nor easily understandable to those accustomed to Western services. Although partaking of Holy Communion is not as frequent as in the Western Church, the congregation always takes a very real and spiritually active part in offering the Eucharistic sacrifice. The pomp and ceremony, the mystery, the closed altar doors, the glory of the hymns—far from intimidating and estranging the faithful, all these make them part of the Sacrament. The beauty, the music, the prayers, detach them from their mundane life; their intellect can be at peace. Because of this powerful mystical participation of all in the Liturgy the Orthodox confession is the same church, with the same ceremony, the same expression the world over, regardless of race, nationality or language.

The next important point is the extreme reverence given the Holy Scriptures. Both the Old and the New Testaments figure largely in the Orthodox daily life. Not only has their study been encouraged from earliest times, but even the illiterate have learned whole portions by heart. The Psalms are part of everyday prayers. The simplest peasant in the most isolated mountain valley in the Carpathians, Balkans or Caucasus is able to cite a Bible verse applicable to any situation in which he may find himself.

Because the Ottoman sovereignty over the Christian peoples of the East was expressed in both religious and national persecution, it followed quite naturally that faith and nationalism should become one and the same thing. Thus people and Church were in very truth united. National kings were anointed by the Church and were part of that Church. This union of Church and State, however, was not always an advantage, but the pros and cons of this point are too lengthy and weighty to be discussed adequately in this short account of Orthodoxy. The important thing is that Orthodoxy has survived Ottoman persecution, Czarism, and is even now surviving Communism. Although the various national groupings are at present a hindrance to concentrated Orthodox action, they have not impaired the Orthodox faith, and no member of any one group seeking the ministrations of the Church is out of communion with any other group. He can freely participate in the Holy Mysteries wherever he finds them.

The Orthodox Church does not speak of Sacraments, but of Holy Mysteries. It does not try to put them into cut-and-dried formulae but accepts them with gratitude and awe. The Easterner has a less inquisitive mind than the Westerner; his mind is more contemplative, less disciplined, but profounder than the Western mind. Where the latter wants definitions, clear intellectual understanding and perception, the former will seek the depths and is content with undefined contacts with the intangible. Perhaps because of long persecutions, he has been thrown more upon himself, and has had to go deeper into reality by himself. There has been less definition and therefore less divergency of opinion. When there have been revelations, their authenticity has not been judged by schooled contemporary minds, but has been held up for judgment by the Church's tradition. If such revelation was found to be in accord with that tradition, it was accepted. The Orthodox Church has been less eager than the Western churches to move with the times, for it feels that it holds the eternal verities. At the same time, it has remarkable adaptability and independence of movement with which to break with any custom when circumstances demand. For example, when Communist Serbia declared Christmas Day a working day so that church services could not be attended, Liturgies were read from midnight on, every two hours until morning, despite the fact that tradition long has ruled that only one Mass in twenty-four hours was to be said at the same altar. Yet, no individual feels that any authority can give him dispensation from the Church's traditional rules, such as that of fasting, which, for the Orthodox, is extremely severe. He feels that the Church's rules were divinely inspired when the Church was founded and no human has either the power or the right to change them or to add to them.

It is a very important factor in the discipline of the Orthodox Church, and largely constitutes its surviving power, that its principles are so deeply ingrained in the laity that the law of the Church is often stronger in them than in the clergy. For example, the laity will accept the Synod's decisions concerning recognition of other confessions, orders and communions with which it feels not competent to deal, but would never accept new dogmas or the doing away with old ones. And no Orthodox would conceive of changing religion for family reasons or because of a change of community, though we would be very tolerant of a change made from spiritual conviction.

There is a belief that, as the Western Church was founded by St. Peter and St. Paul, so the Eastern Church was founded by St. John. Be this as it may, there is no doubt that the Orthodox Church is greatly influenced by the Gospel and Epistles and the Revelations of St. John, and that of these, the spirituality and beauty of the fourth Gospel is its leading factor. The very term "Mystery" for "Sacrament" comes from St. John. An example of the Church's attitude is in the passage in St. John 3:1-21 which tells of our Lord's discussion of the spiritual rebirth of man with Nicodemus; even after Jesus' explanation Nicodemus does not understand. Jesus says: "Art thou a master of Israel and knowest not these things?" and then goes on to explain at length His nature and the way to salvation. The Orthodox Christian does not question but believes in the rebirth of man through the Holy Mysteries which the Church has guarded for him direct from our Lord.

These Holy Mysteries or Sacraments are seven in number—Baptism, Chrismation (equivalent to Western Confirmation), Communion, Penance, Holy Orders, Matrimony and Unction. Let us go over these seven Mysteries and explain the Orthodox catechism, known as "The Faith of the Saints."

A Holy Mystery or Sacrament "is a visible ritual performance through which the invisible saving power called God's grace bestows wonderful gifts upon the recipients."1

Since the word "grace" is so often misunderstood, I believe it is well before going further, to declare the Orthodox definition of the word: "God's grace is God's gift which the Father gives men through the Holy Spirit because of the merits of the Son."2

Baptism is the first Holy Mystery, and by it the baptized person is cleansed of all sin, original and personal, and as a newborn child of God, is incorporated into the Church of Christ.

This ceremony is performed by thrice-repeated total immersion in water, in the name of the Holy Trinity—of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Ghost. The three immersions represent death to sin against the Trinity, and the three risings mean the life in and to the Holy Trinity. The Church's authority for baptism comes direct from Christ, in His clear commandment to His disciples to teach and baptize all nations (Matt. 28:19), and also His stern warning: "Except a man be born of water and of the spirit, he cannot enter the Kingdom of God." (John 3:5). (To the Orthodox, the death of an unbaptized child means its eventual exclusion from the Christian family on the day of the Last Judgment.) Baptism is also a sign of obedience to the Apostolic practice (Acts 10:44-48, 16:15 and I Cor. 1:16). Above all, it is right because of the love of Jesus who commanded: "Let the children come unto Me," and what Christian would not harken to this call?

Baptism is followed immediately by the Holy Chrismation, the second Holy Mystery, through which a baptized person is armed with strength and wisdom by the Holy Spirit. The priest anoints the forehead, breast, eyes, ears, cheeks, mouth, hands and feet with the Holy Chrism (oil) pronouncing the words: "The seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit. Amen." These words are taken from II Cor. 1:21-22: "He who establisheth us with you in Christ, has anointed us in God who has also sealed us, and given us the earnest of the spirit in our hearts."

Chrismation is an extension of, and a sharing in the unction of our Lord with the Holy Ghost, accomplished by the Father. Therefore, the unction unites us not only to the Spirit, but to the Son.3

The holy oil is prepared and consecrated by the bishops, and its use is thus an equivalent to the laying-on of hands in Confirmation in the Western churches, the transmitting of the Holy Ghost. The Orthodox Church offers no theory about the manner of this transmission, but remembers "that God is a Spirit and must be worshipped in spirit and in truth (John 4:14), especially when we turn to the Person of the Holy Ghost." The Chrism is but the channel "of the invisible and spiritual unction which God pours into the hearts of men whenever and wherever He pleases."4

St. Paul says: "The foundation of God standeth sure, having this seal, the Lord knoweth them that are His." (II Timothy 2:19). The Book of Revelation enumerates the servants of God "sealed" from all tribes. (Rev. 7:3-4).

St. Cyril of Jerusalem puts it this way: "Do not forget the Holy Ghost at the time of your illumination; He is ready to stamp your soul with His seal."

A monk of the Eastern Church writes: "The sealing by the Holy Ghost means therefore that the Spirit imprints on us the Father's likeness; that is, the Lord Jesus Himself. From that moment we do not belong any more to ourselves. We have become . . . the slaves and the soldiers of Christ and His sacrificial co-victims. The first Christians used the expression "to keep the seal" in the sense of remaining faithful."5

Once the new Christian has received the Holy Mysteries of Baptism and Chrismation, he is ready to accept the Holy Eucharist. The first two ceremonies are performed in the transcept of the church. Now the child is brought up to the altar by his godparent. He will now partake, as all faithful Christians do, of the true Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ in the visible form of bread and wine. From now on, this will be the central part of his spiritual life. Although there is no ruling about this, a child, after the first communion following his baptism, usually does not communicate until he is able to do so intelligently—around the age of seven, unless he is mortally ill.

Holy Communion, or the Eucharist, is the center of all Orthodox worship, and is prepared and used in the Divine Liturgy. "The aim of man's life is union with God and deification."6 Deification is not, of course, "a pantheistic identity, but is a sharing through grace of the divine life."7

"This participation takes man within the life of the three Divine Persons themselves, in the incessant circulation and overflowing of love which courses between the Father, the Son and the Spirit, and which expresses the very nature of God. . . . Union with God is the perfect fulfillment with the Kingdom, announced by the Gospel, and that love which sums up all the Law and the Prophets."8

The faithful seek this union through communion. "The Orthodox Church . . . believes that the Sacraments are not mere symbols of divine things, but that the gift of spiritual reality is attached to these signs perceptible by the senses . . . that is, in the Eucharistic mystery, the same grace is present nowadays that was once imparted in the Upper Room. There are two aspects to this: the mystical and the aesthetical. The mystical aspect consists in the fact that Sacramental grace is not the outcome of human effort but is bestowed objectively by our Lord. The aesthetical aspect consists in the fact that the Holy Mysteries bring forth their fruit in the . . . recipient only if that soul is assenting to, and is prepared for it. The Greek Fathers emphasized human freedom in the work of salvation."9 St. John Chrysostom writes: "We must first select good and then God adds what appertains to this office. He does not act antecedently to our will, so as not to destroy our liberty."10

"Clement of Alexandria coined the word "synergy" (cooperation) in order to express the action of these two co-joined energies: grace and human will. This term and idea . . . represents today the doctrine of the Orthodox Church on these matters."11 For this reason, the faithful feel that their active part in the Liturgy is essential, and preparation for making their communion is taken very seriously, preceded always by a day of fasting and by confession.

"Orthodoxy does not agree with the Latin doctrine of Transubstantiation, but believes that Christ who is offered in the mystery of the Holy Supper, is truly there present . . . Orthodoxy does not practice the cult of the consecrated elements outside the Liturgy."12 The Roman Church further makes a great point of difference in the actual moment that the mystery takes place. They fix it at the use by the priest of the words of Institution: "This is My Body . . . This is My Blood."—while the Orthodox say that "the sanctification of the Holy Gifts operates during the entire Liturgy, whose essential part consists in the words of institution of Our Lord following the invocation of the Holy Spirit, and the benediction of the elements ("epiklesis").13

Eucharistic grace fulfills the grace of Baptism and of Chrismation. In the Paschal mystery is found the Lord's Supper, the Passion and the Resurrection, yet the Eucharistic Sacrament is not an end in itself, but a means to spiritual reality greater than the sacraments themselves. Communicating with Christ, we communicate with all His members. "For we being many, are one bread and one body: for we are partakers of that one bread." The Eucharist is the life flow that courses through the whole body of Christ's Church. We do not absorb it; it absorbs us.

For man to be worthy of so great a love by which God gave His only begotten Son to save us from sin and perdition is almost superhuman. It could not be, had not our Lord instituted also the Mystery of Holy Penance when He told us to confess our sins to each other and gave His Apostles the power to remit sins. "Receive ye the Holy Spirit; whosoever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them, and whosoever sins ye retain, they are retained." (John 20:22-23)

Every sin we commit against man, we commit against God, too. There is no sin that does not hurt God. It is not sufficient to confess and make retribution to the person injured, but we should seek also to confess to a priest, successor to the Holy Apostles, who have spiritually inherited the power to forgive sins. There are sins for which there appears, to human understanding, to be no forgiveness. Yet we know of many instances of great sinners who, through true repentance had their sins remitted, and have become great saints.

The Church urges frequent confession, especially before Holy Communion and during illness, so that the soul may ever be ready to stand before the Judgment Seat. In no way is this a control of the faithful's lives by the priesthood. The priest is only the channel through which men gain God's forgiveness. One does not confess to the priest as a person, but to God through the priest. The priest is there to help the penitent formulate his sin and to be the visible transmitter of God's grace of forgiveness. He is the vehicle which Christ instituted for this purpose.

Here, as in all the other Mysteries, the Orthodox Church teaches that "God is not bound to the Sacraments; there is 'One greater than the Temple' (Matt. 12:6) and greater than the Holy Mysteries."14 That is to say, that should death befall a person where he cannot partake of any of the Mysteries, God may yet reach him if his soul is prepared by love and repentance. "Unsearchable are His judgments and His ways past finding out." (Rom. 11:33) When He so wishes it, God does not need the visible ritual performance to bestow His gifts.

The Orthodox Church does not have the dogma of Purgatory. "According to the Orthodox Church, death ends man's probation and immediately after death he is judged. His fate in eternity is determined by his whole moral state at the moment of death."15 "We believe that the souls of the departed are in repose or torment as each one wrought, for immediately after the separation from the body, they are pronounced either for bliss or for suffering and sorrow, yet we confess that neither the joy nor the condemnation are as yet complete. After the general resurrection, when the soul is united to the body, each one will receive the full measure of joy or condemnation due to him for the way in which he conducted himself, whether well or ill." (Confessions of Dositheus at the Synod of Constantinople, 1672) .

The Orthodox Church makes no hard and fast pronouncement, any more than do the Gospels, as to what the state of the soul is, and where it resides between death and the day of Judgment. We know there is a Heaven and a Hell, and that they are a state of the spirit. "Neither shall they say lo here! or lo there! for behold, the Kingdom of God is within you." (Luke 17:21). Our Lord also said: "In My Father's house there are many mansions; if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you." (John 14:2).

We also firmly believe that man's probation and his free choice are here on earth, and that "Christ's power to forgive sins is on this side of the grave", as Theophylact says in St. Luke 5:24, commenting on the words of Christ (when He says "that the Son of man hath power on earth to forgive sins"). Notice that it is on earth that sins are forgiven. So long as we are on earth, we can blot out our sins; after we have departed from the earth, we are no longer able to blot them out by confession, for the door is shut!16 Androutsos has said: "The absolution is a full, complete, and entire forgiveness and remission of all sin and a restoration and return to the state of grace."17 Furthermore, the idea of the necessity of propitiating the Divine righteousness by means of penalty is foreign to the Orthodox conception of an all loving and just God, limiting His powers.

Certain grievous sins are unforgivable, not as from the powerlessness of God or the Church, but because by their nature they make those committing them unrepentant and callous, so that in such cases divine Grace cannot operate. (Androutsos. Gavin p. 360)

The fifth Holy Mystery is Holy Orders. It is the mystery by which the Holy Spirit, through the laying-on of hands of bishops, gives grace and authority to the newly ordained priest or bishop to perform the Mysteries, and to conduct the religious life of the people. Through the touch of consecrated hands, this spiritual power is communicated to the person ordained, and thus the lawful continuity, authority and ministry of the Church was and is secured. (I Timothy 4:14 and 5:22).

Bishops have this grace because they are the successors of the Apostles. Christ Himself is our High Priest. (Heb. 5:4-6). He is the source of all power and authority in His Church, and gave the power to the Apostles to teach, to heal, and to forgive the sins of men.

There are three degrees of Holy Orders: bishops, priests and deacons. A bishop can administer all seven mysteries: the priest, all except Holy Orders: and the deacon assists both the bishop and the priest, but by himself, cannot perform any of the Sacraments.

A word should be inserted here about the monastic orders in the Orthodox Church. There are no differing orders in the sense that the Western Church uses the term, that is to say Franciscans, Benedictines, etc. There is a very strong monastic tradition in the Eastern Church. Since the time of St. Anthony of Egypt all the monasteries and convents follow the prescriptions of St. Basil the Great. Their chief objective is contemplative prayer. There is no set rule of probation or novitiate as in the West. There are three grades of monks: The lowest (Greek: rasophore, Slavic: rejasonosts) may be entered very shortly after the aspirant comes into the monastery. The second (Greek: stavrophore, Slavic: skhimnik) can be entered after three years, and if the postulant is over 25 (and in the case of a woman over 40). They then take four oral vows—of poverty, obedience, chastity and stability. To reach the third degree, megaloskhomos, to which only a few attain, takes 20 to 30 years of preparation. These monks devote themselves entirely to contemplative prayer, becoming hermits and taking the vow of silence. This is the pinnacle for which they are trained during the years of discipline in the communal life of the first two degrees. Many never pass the first two degrees; nonetheless, all are monks; the degree is one of spiritual attainment. Not all monks are priests (hiermonk) and no distinction is made between them if they are. All Bishops have to be monks of the first or second degree. If a Bishop should attain to the third degree, he has to resign all episcopal and sacerdotal functions except the celebration of the Liturgy, because of the extremely penitential and strict discipline and the long periods of silence.

Many monasteries and convents devote themselves to the care of the sick and suffering and also education; but these are side activities. The reason for monastic life in the East is prayer and contemplation, the drawing of the soul ever closer to God.

The sixth Holy Mystery is that of Matrimony, which represents the union of two souls and two bodies, and sanctifies this union that they are no more two, but one body.

The seventh Holy Mystery is Holy Unction, which consists of the priest's prayers and the anointing of a sick person with blessed oil through which God's grace affects the recovery of the sufferer. By sickness is meant both that of body and soul, for Unction heals the body of its infirmities as it cleanses the soul of its sin. St. James advises: "Is any sick among you? Let him call for the Elders of the Church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord, and the prayer of faith shall raise him up; and if he has committed sins they shall be forgiven him." (James 5:14-15). In this, the priest follows the tradition of the Apostles who, directed by Christ Himself, preached the Gospel, and among other miracles they "anointed with oil many that were sick and healed them." (Mark 6:13). This mystery is not necessarily reserved for the dying, but is administered also to any sufferer.

Thus the Church presides over the mysteries of all needs of man through its hierarchy.

In the Apostles, Our Lord laid the foundation of the hierarchy: to deny this would be to oppose the will of the Lord. Of course, the Apostles, by their consecration did not become equal or like Our Lord, vicars of Christ, or substitutes for Christ . . . Our Lord Himself lives invisibly in the Church "always now and forever and to eternity"; the hierarchy of the Apostles did not receive power of place, but power to communicate the gifts necessary to the Church . . . to the hierarchy belongs the authority to be mediators, servants of Christ18 from whom they received full power of their ministry as such: "the hierarchy represented by the episcopate becomes a sort of external doctrinal authority which regulates and moralizes the dogmatic life of the Church. . . . Inasmuch as the Church is a unity of faith and beliefs, bound together by the hierarchic succession, it must have its doctrinal definitions supported by the whole power of the Church. In the process of determining these truths the episcopate gets together with the laity, and appears as representative of the laity."19 "With us, the guardian of piety is the very body of the Church, that is, the people themselves, who will always preserve their faith unchanged." (Epistle of the Eastern Patriachs, 1849). This gathering is called the Synod, and is the Church's supreme authority.

Every Christian receiving Baptism becomes part of the Church and is responsible as a member for guarding the faith and also spreading it abroad. When the Church is spoken of, the entire Church is meant—the hierarchy, the laity—the living and the departed.

"Here we touch the very essence of Orthodox doctrine of the Church. All the power of Orthodox ecclesiology is concentrated on this point. Without understanding the question, it is impossible to understand Orthodoxy; it becomes dynamic compromise, a middle way between Roman and Protestant viewpoints. The soul of Orthodoxy is sobernost—according to the perfect definition of Khomiakov; in this one word of his is contained a whole confession of faith. . . .20 It is a Slavonic term but used in many Orthodox churches even by those whose language is basically Latin as for instance in the Romanian. It is used in place of "Catholic" in the Creed "Cred intr' una Sfanta Soborniceasca si Apostolica Biserica" (I believe in one "sobornical" and Apostolic Church).

"What then is sobornost?"

The word is derived from the verb "sobirat" to reunite, to assemble. From this comes the word "sobor" which, by a remarkable coincidence means both "council" and "church". Sobornost is the state of being together. . . . To believe in a "sobornaia" church is to believe in a Catholic Church, in the original sense of that word, and in a church that assembles and unites—it is also to believe in a conciliar church. Orthodoxy, says Khomiakov, is opposed to both authoritarianism and to individualism; it is a unanimity, a synthesis of authority. It is the liberty in love which unites believers. In the word "sobornost" is expressed all that.21

When the Church speaks, it is this sobor which speaks through the ages from its very foundation. All new problems are judged by the judgment of the entire Church through the inspiration of the Holy Ghost. Thus "the Church is infallible, not because it expresses the Truth correctly, from the point of view of practical expediency, but because it contains the Truth. The Church, Truth, infallibility, these are synonyms."22

Another important element in the Orthodox faith is one without which its spiritual life would not be complete. This is the Communion of Saints, "which is a sharing of the prayers and good works of the heavenly and earthly Christians, and a familiar intercourse between ourselves and the glorified saints."23

The worship of saints must not be misunderstood or confused with the adoration due to God alone. It is, in fact, more correctly termed veneration. St. John Damascene says that veneration "is paid to all that are endowed with some dignity." But this relationship is not one of respect and honor to those who have lived good and saintly lives, but "just as a living Christian can beg the intercession of another living Christian, so we commend ourselves to the prayers of the saints."24