The Mystery of the Passion of Charles Peguy

ROBERT ROYAL

When a true genius is born, nothing in the family or its circumstances allows us to predict the new arrival.

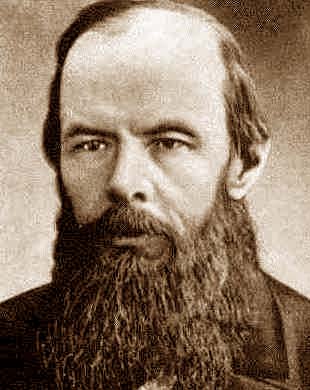

Charles Péguy

(1873-1914)

Like many other pre-Vatican II figures, Péguy has been in eclipse the past few decades, even in France. The secular world neglects him for complicated religious and political reasons. But gifted minds in their own right as different as the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel, the Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, and the British poet Geoffrey Hill have tried to bring us back into contact with his great spirit. In fact, Péguy’s life gives moving witness that a great spirit and heart outweigh even genius. If he ever gets a fair hearing, Péguy may one day be recognized as a figure on the order of Kierkegaard or Newman, and perhaps something more besides.

Péguy was born in 1873 near Orléans, Joan of Arc’s birthplace, and grew up with a mother and grandmother who were basically illiterate. They earned a bare living recaning chairs sixteen hours a day, seven days a week. Péguy learned the trade and also helped out, well into his teens, with the annual harvests in the region. Though he showed great gifts the moment he entered school, Péguy was as close to a peasant as any major literary figure who ever lived.

The genius of Péguy lies mainly in the ways he tried to bring simple truths to bear on the whole modern world. Sheer intellect would take him to the Ecole Normale Superieure and the Sorbonne, the twin summits of the French educational system. But except for some activity in political causes, he would live a largely uneventful life — at least in the way most people conceive of events. His activity consisted in a wide-ranging attempt to retrieve an authentic spiritual life from the various incrustations that were making it difficult to find, even for simple people. Despite the underlying simplicity of his words, they have a brilliance and authority that revitalize politics, mysticism, war, peace, love, honor, and death. In him, the timeless depths of the classical and Christian past suddenly find a new voice that is also a prophetic and urgent message to the present.

Péguy was killed by a bullet through the head during the Battle of the Marne in 1914. He had anticipated his death in a poem:

Blessèd are those whom a great battle leaves

Stretched out on the ground in front of God’s face,

Blessèd the lives that just wars erase,

Blessèd the ripe wheat, the wheat gathered in sheaves.

It was a dramatic end to a heroic life. He was barely forty.

In a different age, Péguy might have founded a religious order. As it turned out, he did something even more difficult: He lived a life of complete intellectual and spiritual integrity in the modern world.

Paying the Price

Péguy is never a mere writer — what he called an intellectual — i.e., someone who stands outside life as an observer. He risked himself, his wife and children, and “the first of treasures . . . peace of heart” for the truth. Once, when someone was making a point, he interrupted: “You’re right, but you have no right to be right unless you are willing to pay the price of demonstrating the rightness of truth.” Even eighty years after his death, for those who know him, Péguy remains a real presence. When you read him, your eyes don’t merely follow a string of words, you enter a passionate current of life.

As a young man in Orléans, Péguy gravitated toward simple workers and peasants who were interested in freedom and learning, even if they had to pursue them in the evening after long hours at work: “I consider it a personal blessing to have known, in my earliest youth, some of those old republicans; admirable men; hard on themselves; and good for events; I learned through them what it means to have a whole and upright conscience.” Several sober intellectuals have disputed whether this exuberant portrait of the old France is accurate. Péguy was as skeptical as anyone of romantic fantasies, but he is there to witness that such people existed.

Many people today blithely invoke civil society as a counterweight to much that is wrong in the modern world. Péguy would have agreed, but for him popular virtues had deep roots in classical and Christian culture. Without that living support, even the peasants and workers became corrupt. By around 1880, he would argue, the old pride in hard work, productivity, and craftsmanship was beginning to pass.

Though Péguy was an activist for workers, he deplored the new attitude among labor groups of demanding the largest compensation for the least work and even, something unthinkable in the old system, of destroying tools and machinery during strikes. In the old days, there had been more independence and simple virtue: “when a worker lit a cigarette, what he was going to tell you was not what some journalist had said in the morning newspaper. The free-thinkers in those days were more Christian than pious people today.”

Both the Church and the republic, he claimed, had contributed to this disaster in their mistaken attacks on one another. (Remnants of these attitudes surfaced when John Paul II visited France earlier this year: Five thousand people demonstrated when the pope praised the ancient king, Clovis, as if his visit were a prelude to restoring the ancien régime). For Péguy the true Catholic and true republican virtues were parallel achievements, producing saints on the one hand and heroes on the other. The decline of Christianity, he warned, was part of the same evil spirit leading to the decline of the republic, a lesson we still have not absorbed.

Maligned Reputation

Péguy’s talk of his peasant world and workers’ virtues harmed his reputation in some quarters. Like Nietzsche (though with even less justice), Péguy was portrayed by a few Nazi sympathizers during World War II as an advocate of a kind of popular French nationalism and racism. The Nazi version of the Volk and Péguy’s appeal to the peuple could not have been more different: The first sought exclusion and racial distinctions, the second inclusion and human brotherhood. But unscrupulous Nazi sympathizers like Drieu La Rochelle, editor of the collaborationist Nouvelle Revue Française during the war, took excerpts out of context to make Péguy, then a popular hero from World War I, look like an advocate of blood and soil. All this has been exposed beyond dispute by scholars. But while Nietzsche, who has certain uses in today’s academy, has been given a free pass despite his Nazi admirers, Péguy, clearly because of his Catholicism and embrace of the old world, remains in limbo.

Ironically, at the same moment in the 1940s, Jacques Maritain was broadcasting radio messages to occupied France from New York, rightly invoking Péguy’s name in far different company. Maritain worked for Péguy as a young man in Paris. He spoke both from personal acquaintance and a just appraisal of Péguy’s heroic spirit when he addressed France as “ancient land of Joan of Arc and Péguy” and the French as “companions of Joinville and Péguy, people of Joan of Arc.” In London, DeGaulle made similar apppeals.

In America, Julian Green’s selections and translations from Péguy were also just appearing: Basic Verities and Men and Saints, among others. Green did a brilliant introductory job (and rightly kept Péguy’s incomparable French on the pages facing the translations), but his work also has serious limitations.

The brief passages Green chose give the impression that Péguy is an aphoristic writer like Chesterton:

“Kantianism has clean hands because it has no hands.”

“Tyranny is always better organized than freedom.”

“Homer is still new this morning, and nothing perhaps is as old as today’s newspaper.”

All this is to the good, but Péguy also needs to be read in larger chunks to see the sheer power and trajectory of his genius.

Merited Attention

In 1952, Alexander Dru, the translator of Kierkegaard, published extended segments from two of Péguy’s greatest essays. Several of the longer poems have been translated in full. But we still need a good-size anthology of Péguy’s prose in English. His reading of history and analysis of the real roots of our spiritual crisis alone would make such a volume invaluable. It would also reveal Péguy’s most salient trait — an unflagging passion for justice and truth whatever the cost.

Péguy never finished his university studies because he was repeatedly sidetracked by situations demanding charity and action. He had sticks broken on his back in demonstrations. He broke with allies who struck dishonorable compromises. If he had wanted to play along with what was already becoming a corrupt system and corrupting alliance between politicians and intellectuals, he could have had a secure existence as a university professor. Instead, he chose the path of truth — along with poverty and isolation.

Amid various struggles for workers’ rights and relief efforts, Péguy became a socialist of sorts because he believed that true socialism sought real brotherhood and respect among men. He was young, and the world had not yet seen any socialist regimes. But he intuited the true spirit behind socialist movements when he came into contact with actual socialist practice. Péguy was by nature incapable of the kinds of lies and partisanship that make up most party politics. His verdict about such things is a phrase known to many people who have otherwise never heard of Péguy: “Everything begins in mysticism (le mystique) and ends in politics.” This formula summed up more than twenty years of political experience.

Péguy the socialist also became a supporter of Dreyfus, the French Jewish officer wrongly accused of spying for Germany. He started a journal, the Cahiers de la Quinzaine, to defend these and other just causes because he discovered at an international convention that the socialists practiced the same kind of partisan lying and injustice that he had associated with bourgeois conservatives. Journals like his were forbidden to criticize positions taken by the movement. The socialist mystique was betrayed by socialist politics.

For Péguy, the root of any mystique was remaining fidèle (faithful) to truth and justice despite party commitments. He would refuse to impose an orthodoxy even on writers for the Cahiers: “A review only continues to have life if each issue annoys at least one-fifth of its readers. Justice lies in seeing that it is not always the same fifth.” Without support from either right or left in a sharply ideological France, his fidelity led to a passion in a more Christ-like sense, persecution and gradual economic strangulation by established powers.

Three Mysteries

He even came to feel himself at odds with the Dreyfusards. They had begun in a mystical, idealistic mode, fighting for three mystiques: the Jewish mystique, with its long history of suffering for the right since Old Testament times (the Nazi collaborators were careful to hide this pro-Jewish Péguy); the Christian mystique, founded by a just man wrongly accused; and the French mystique, which in both its republican and Christian forms believed in justice for all. For Péguy, being a Dreyfusard meant the spiritual and moral defense of all three.

Unhappily, Péguy detected within the Dreyfusards, too, impure political elements at odds with its mystique. The socialist Combes government, for example, used the emotional repercussions of the Dreyfus case to close Catholic schools and monasteries (Catholics had largely supported the military and the charges against Dreyfus). As a man who valued discipline, courage, and the right use of military power in just causes, Péguy particularly detested what he saw as an anti-French, anti-military, near traitorous element among some Dreyfusard:

“Some people want to insult and abuse the army, because it’s a good line these days. . . . In fact, at all political demonstrations it is a required theme. If you don’t take that line you don’t look sufficiently progressive . . . and it will never be known what acts of cowardice have been motivated by the fear of looking insufficiently progressive.”

Somewhere along this path of betrayal by the socialists and Dreyfusards, Péguy returned to the Church. A friend stopped in to see Péguy when he was sick in bed at home. After a long conversation, Péguy merely remarked as the friend was leaving, “Wait. I haven’t told you everything. I’ve become a Catholic.” No great explanations were later forthcoming. On the few occasions when he wrote of the conversion, Péguy didn’t even use the word, preferring to speak of the “deepening” of his passion for truth, justice, and brotherhood, which found its fullest scope in Catholicism.

But he did not find that the Catholic parties were doing much better than the others in keeping their politics from overwhelming their mystique. The Catholic Church seemed to have betrayed its mystique by becoming a temporal party in France and elsewhere. Péguy thought that if it dropped clerical politics and returned to its spiritual greatness and concern for the poor, the Church would enter into a period of massive renaissance. Fidelity to the Gospel, which in the realm of mystiques did not exclude what was noble and good in other traditions, now became the overruling passion of his life.

Péguy’s conversion brought with it not only spiritual renewal but fresh literary inspiration as well, including a turn to poetry. In 1909, he wrote his book-length poem The Mystery of the Charity of Jeanne d’Arc, a stunning evocation of Joan’s youth in Péguy’s own Orléans, which shows the peasant roots of her charity and how the story of Christ Himself needs to be seen in its simple, passionate, popular elements. The battles and heresy trial that most writers think are the heart of Joan’s saga have only secondary importance for Péguy. He had always been a facile writer, but his output became greater — in every sense — after the conversion.

Passion and Fidelity

In God’s providence, Péguy found himself subject to new trials of passion and fidelity around 1910 when — without any previous warning — he fell deeply in love. Madame Geneviève Favre, Jacques Maritain’s mother, was close to Péguy at the time and has left a lengthy record of the “terrible hurricane” that struck him. For many years, the identity of the woman was kept confidential because of the various actors still living, including Péguy’s wife. We now know that she was Blanche Raphael, a young Jewish friend of Péguy’s since his university days and a collaborator in several projects. Once that passion ignited, it became, like everything else in Péguy’s life, as much an eternal as a personal question.

Unlike many men who undergo similar experiences at his age, Péguy remained perfectly fidèle — to everyone — and therefore suffered immensely. He wanted to respect all elements of the reality that had been presented to him. He could not think of being unfaithful or breaking with his wife, even though he might have gotten an annulment because they had been married outside the Church. But neither would he simply ignore his feelings for Blanche, which he regarded as a reality to be acknowledged. For the four years until his death, therefore, even after Blanche’s marriage to another man, Péguy would struggle with himself and with God.

Most Catholics repeat, “Thy will be done,” every day without noticing what they are saying: Péguy learned the cost of such prayers.

Some of his finest poetry appeared during this period. To understand a poem like the one he wrote to the Virgin of Chartres under the title Prayer of Confidence, though, it is necessary to know the other female figure behind the one he is openly addressing. That poem concludes:

When we sit down at the cross formed by two ways

And must choose regret along with remorse

And dual fate forces us to pick one course

And the keystone of two arches fixes our gaze,

You alone, mistress of the secret, attest

To the downward slope where one road goes.

You know the other path that our steps chose,

As one chooses the cedar for a chest.

And not through virtue, which we don’t possess.

And not for duty, which we do not love.

But, as carpenters find the center of

A board, to seek the center of wretchedness,

And to approach the axis of distress,

And for the dumb need to feel the whole curse,

And to do what’s harder and to suffer worse,

And to take the blow in all its fulness.

Through that sleight-of-hand, that very artfulness,

Which will never make us happy anymore,

Let us, o queen, at least preserve our honor,

And along with it our simple tenderness.

Suffering, honor, tenderness: Péguy seems to have come to an understanding through this experience that pain and even a vulnerability to sinfulness often are the only ways to open up channels by which real grace can reach us, particularly those of us who think our faith and morals are already enough.

Once he embraced them fully, fidelity and abandonment to the divine will started to become a full-time job. When Péguy’s son Marcel fell seriously ill, he turned the son over to the protection of the Virgin and “walked away,” promising that if Marcel recovered, Péguy would make a walking pilgrimage between Notre Dame in Paris and Notre Dame in Chartres, a good sixty miles. Marcel recovered and Péguy kept his vow. He would later repeat the pilgrimage for other causes. In the interwar years, as the cult of Péguy grew in France, thousands of people reenacted this concrete devotion yearly. Even today, when hardly anyone reads Péguy anymore and many ancient devotional practices have all but disappeared, large groups of fidèles make the trek out of solidarity with Péguy.

It was also around the time of Marcel’s illness that Péguy wrote one of the greatest and most unjustly neglected poems of the century, The Portal of the Mystery of Hope. For Péguy, both fidelity and hope are not static habits or concepts, but dynamic, living forces. It was an insight he had learned and developed from an early friend, Henri Bergson. Mere abstract doctrines of fidelity or hope may themselves become obstacles to the spirit. By contrast, real hope is the forward thrust of life; someone who is in despair, literally without hope, cannot be argued back into another attitude. Hope can only be received from God; it reconnects the hopeless person “to the source, to a reawakening in him of the child.”

A Better Tomorrow

In the poem itself, which recently has been ably translated by David L. Schindler Jr., hope is portrayed as a little child, but a child of greater immediate urgency than her serious older sisters faith and charity. Besides, says Péguy (or rather, says God: Péguy is not afraid to put words in the Deity’s mouth), hope is one of the most remarkable things in the world:

The faith that I love best, says God, is hope.

Faith doesn’t surprise me.

It’s not surprising

I am so resplendent in my creation. . . .

That in order really not to see me these poor people would have to be blind.

Charity says God, that doesn’t surprise me.

It’s not surprising.

These poor creatures are so miserable that unless they had a heart of stone, how could they not have love for one another.

How could they not love their brothers.

How could they not take the bread from their own mouth, their daily bread, in order to give it to the unhappy children who pass by.

And my son had such love for them. . . .

But hope, says God, that is something that surprises me.

Even me.

That is surprising.

That these poor children see how things are going and believe that tomorrow things will go better.

That they see how things are going today and believe that they will go better tomorrow morning.

That is surprising and it’s by far the greatest marvel of our grace.

And I’m surprised by it myself.

And my grace must indeed be an incredible force.

Among many other firsts, Péguy may be the only writer in history to have God pronounce something “unbelievable,” the even greater irony being that it is the force of his own grace that God finds so.

The way this is conveyed draws us into the very dynamic of hope. Péguy was always an incantatory writer, almost hypnotizing in his repetition of words and phrases as a way to involve the reader in the dynamic rather than merely describing. André Gide once wrote brilliantly of this procedure:

Twelve sentences would have sufficed for me summing up these 250 pages. But the repetitions . . . are intrinsic and a part of the whole. . . . Péguy’s style is like that of very old litanies . . . like Arab songs, like the monotonous songs of the Landes; one could compare it to a desert; a desert of alfalfa, of sand, or of pebbles . . . each looks like the other, but is just a little different, and this difference corrects, relinquishes, repeats, or appears to repeat, accentuates, affirms, and always more certainly one advances . . . the believer prays the same prayer throughout, or at least, almost the same prayer . . . almost without his being aware of it and, almost in spite of himself, beginning all over again. Words! I will not leave you, same words, and I will not acquit you while you still have something to say, “We will not let Thee go, Lord, Except Thou bless us.”

To read Péguy is, as with no other mere writer, to become part of that demand for a blessing.

We have lost or mislaid a great portion of the riches of the Catholic faith in recent years. Some of it is so far gone that it will take an immense effort of preparation to put us in a state to recover it again. Péguy has been one of the partial casualties of that history. But unlike many other figures, he speaks with a directness and vitality about things quite close to our own experience. To reconnect with him we do not need anything other than eyes to see and ears to hear. This century has been a mess, and still worse for failure to heed prophetic voices like his. If we are looking for a Catholic renaissance and a restoration of our civic virtues in the new millennium we will find them only by recovering the work and imitating the lives of men like Charles Péguy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Royal, Robert. “The Mystery of the Passion of Charles Péguy.” Crisis 14 no. 11 (December 1996).

CATHOLIC FICTION AND THE RESTORING CULTURE BY MICHAEL O'BRIEN

Download with Vixy

)/App_Themes/White/Images/ctatmonastica.jpg)

)/App_Themes/White/Images/ctatmonjos.jpg)

_4.jpg/220px-Benedykt_XVI_(2010-10-17)_4.jpg)