“Only a permanent formation of the heart and mind can actually create intelligibility and participation which is more than one external activity, which is an entering of the person, of his or her being into communion with the Church and thus in fellowship with Christ.”—Pope Benedict XVI this morning, in his annual address to the clergy of Rome, in the Paul VI Audience Hall in Vatican City; the talk was delivered without a written text, as in a conversation, or university seminar

Pope to Rome’s priests: The Second Vatican Council, As I Saw It

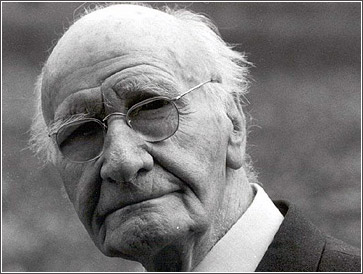

The remarkable thing about Pope Benedict's talk today to the clergy of Rome, several thousand strong, was that he did not speak from a prepared text. He spoke freely, familiarly. It was an impressive performance.

For nearly 50 minutes, the 85-year-old pontiff — who on Monday stunned the world with the abrupt announcement of his decision to leave the papacy on February 28 — spoke "a braccio" ("off the cuff") somehwat as a professor may speak to his students in a university seminar.

It seemed that this "professor Pope" has, in the final days of his papacy, in fact truly become the "professor Pope."

It is as if the weight of speaking with magisterial authority, which already in the past seemed to make this Pope occasionally uncomfortable (as when he issued his books on Jesus under the names both of "Joseph Ratzinger" and of "Pope Benedict XVI") is already, two weeks before his resignation, being lifted off of his shoulders.

His manner of speaking today reminded me of several conversations I was able to have with him in the 1990s, when he, as Cardinal Ratzinger, spoke with me, a young journalist, about some of the matters he discussed today.

Benedict seemed very much at ease, though he was evidently a bit tired (one of his eyes sometimes almost closed as he spoke).

The Pope offered a personal account to Rome's clergy of his own experience of the Second Vatican Council, and of what the Council intended.

Because it is one of the last times he will speak publicly to a large audience as Pope, the talk was closely followed by Vatican watchers.

What was the Pope's "message" as he prepares to renounce his office on February 28?

Essentially, that the documents of Vatican II were works of great value which responded to real concerns and problems facing the Church, but which were later distorted, often by the world's media, which had their own agenda, leading to much confusion and "misery."

In particular, Benedict said that the popular understanding of Vatican II has been distorted presentations of the Council as a political struggle for "popular sovereignty" in the Church. This "Council of the media" was responsible for "many calamities, so many problems, so much misery," the Pope said. He listed the miseries: "Seminaries closed, convents closed, liturgy trivialized."

But the Pope said that the "true Council" is today "emerging with all its spiritual strength," and he called on the priests to "work so that the true Council with the power of the Holy Spirit is realized and the Church is really renewed."

At the very beginning if his papacy, almost 8 years ago, Benedict called for a reading of Vatican II "in continuity" with the Church's 2,000-year doctrine, not as a "rupture" with that past. His talk today was a re-emphasis of this teaching.

Before the Pope's talk, the priests greeted him with a standing ovation and a shout of "Viva il Papa!" ("Long Live the Pope!"). Cardinal Agostino Vallini, the vicar for Rome, read a short tribute to the Pope, comparing the occasion to the departure of St. Paul from Ephesus in the Acts of the Apostles.

The cardinal then began to weep slightly, saying, "in the name of all the priests of Rome, who truly love the Pope, we commit ourselves to pray still for you and for your intentions, so that our grateful love may become, if possible, even greater."

==============================

The Vatican Radio Transcription of the Pope's February 14 Talk to the Clergy of Rome (slightly edited for clarity)

No official text of the talk has yet been made available — because there was no official written text to begin with — but Vatican Radio today published a transcription of nearly all of the Pope's talk.

Still, because there are a number of small mistakes and omissions in the text, I have edited it very slightly in the version published below.

The Vatican Radio text may be found in its original form at this link:

http://en.radiovaticana.va/news/2013/02/14/pope_to_rome's_priests:_the_second_vatican_council,_as_i_saw_it/en1-664858

"It is a special and providential gift," began the Pope, "that, before leaving the Petrine ministry, I can once again meet my clergy, the clergy of Rome. It is always a great joy to see how the Church lives, and how in Rome, the Church is alive: there are pastors who in the spirit of the supreme Shepherd, guide the flock of Christ."

"It is a truly Catholic and universal clergy," he added, "and is part of the essence of the Church of Rome itself, to reflect the universality, the catholicity, of all nations, of all races, of all cultures.”

“At the same time, I am very grateful to the Cardinal Vicar who is helping to reawaken, to rediscover the vocations in Rome itself, because if, on the one hand, Rome is the city of universality, it must be also a city with its own strong, robust faith, from which vocations are also born. And I am convinced that, with the help of the Lord, we can find the vocations He Himself gifts us, guide them, help them to develop and thus help the work in the vineyard of the Lord."

"Today," continued the Pope, "you have confessed the Creed before the Tomb of St. Peter: in the Year of the Faith, I see this as a very appropriate, perhaps even necessary, act, that the clergy of Rome meet at the Tomb of the Apostle of which the Lord said, 'To you I entrust my Church. Upon you I build my Church.’ Before the Lord, together with Peter, you have confessed: 'you are Christ, the Son of the living God.' Thus the Church grows: together with Peter, confessing Christ, following Christ. And we do this always. I am very grateful for your prayers that I have felt, as I said Wednesday, almost physically. Though I am now retiring to a life of prayer, I will always be close to all you and I am sure all of you will be close to me, even though I remain hidden to the world. "

"For today, given the conditions of my age," he said, "I could not prepare a great, real address, as one might expect, but rather I thought of chatting about the Second Vatican Council, as I saw it."

The Pope began with an anecdote: "In 1959, I was appointed professor at the University of Bonn, which is attended by students, seminarians of the diocese of Cologne and other surrounding dioceses. So, I came into contact with the Cardinal of Cologne, Cardinal Frings. Cardinal Siri of Genoa — I think it was in 1961 — had organized a series of conferences with several cardinals in Europe, and the Council had invited the archbishop of Cologne to hold a conference, entitled: 'The Council and the World of Modern Thought.' The Cardinal invited me — the youngest of the professors — to write a project; he liked the project and proposed this text, as I had written it to the public, in Genoa."

"Shortly after," he continued, "Pope John invited him to come [to Rome] and he was afraid he had perhaps said maybe something incorrect, false, and that he had been asked to come for a reprimand, perhaps even to deprive him of his red hat... (priests laughing). Yes... when his secretary dressed him for the audience, he said: 'Perhaps now I will be wearing this stuff for the last time...' (the priests laugh). Then he went in. Pope John came towards him and hugged him, saying, 'Thank you, Your Eminence, you said things I have wanted to say, but I had not found the words to say'... (the priests laugh, applaud) Thus, the Cardinal knew he was on the right track, and I was invited to accompany him to the Council, first as his personal advisor, then — in the first period, perhaps in November '62 — I was also appointed as an official peritus [expert] for the Council.”

Benedict XVI continued: "So, we went to the Council not only with joy, but with enthusiasm. The expectation was incredible. We hoped that everything would be renewed, that a new Pentecost really would come, a new era of the Church, because the Church was not robust enough at that time: the Sunday practice was still good, even vocations to the priesthood and religious life were already somewhat fewer, but still sufficient. But nevertheless, there was the feeling that the Church was going on, but getting smaller, that somehow it seemed like a reality of the past and not the bearer of the future. And now, we hoped that this relationship would be renewed, changed, that the Church would once again source of strength for today and tomorrow."

The Pope then recalled how they saw "that the relationship between the Church and the modern period was one of some ‘contrasts’ from the outset, starting with the error in the Galileo case, "and the idea was to correct this wrong start" and to find a new relationship between the Church and the best forces in the world, "to open up the future of humanity, to open up to real progress."

The Pope recalled: "We were full of hope, enthusiasm and also of good will."

"I remember," he said, "the Roman Synod was considered as a negative model" where — it was said — they read prepared texts, and the members of the Synod simply approved them, and that was how the Synod was held. The bishops agreed not to do so because they themselves were the subject of the Council. So — he continued — even Cardinal Frings, who was famous for his absolute, almost meticulous, fidelity to the Holy Father, said that the Pope has summoned the bishops in an ecumenical council as a subject to renew the Church.

Benedict XVI recalled that "the first time this attitude became clear, was immediately on the first day."

On the first day, the Commissions were to be elected and the lists and nominations were impartially prepared. And these lists were to be voted on. But soon the Fathers said, "No, are not simply going to vote on already made lists. We are the subject."

They had to move the elections — he continued — because the Fathers themselves wanted to get to know each other a little, they wanted to make their own lists. So it was done.

"It was a revolutionary act," he said, "but an act of conscience, of responsibility on the part of the Council Fathers."

So, the Pope said, a strong activity of mutual understanding began. And this, he said, was customary for the entire period of the Council: "small transversal meetings." In this way he became familiar with the great figures like Father de Lubac, Danielou, Congar, and so on. And this, he said "was an experience of the universality of the Church and of the reality of the Church, that does not merely receive imperatives from above, but grows and advances together, under the leadership, of course, of the Successor of Peter."

He then reiterated that everyone “arrived with great expectations" because "there had never been a Council of this size," but not everyone knew how to make it work. The French, German, Belgian, Dutch episcopates, the so-called "Rhineland Alliance,” had "the most clearly defined intentions."

And in the first part of the Council, he said, it was they who suggested the road ahead, then it’s activities rapidly expanded and soon all participated in the "creativity of the Council."

The French and the Germans, he observed, had many interests in common, even with quite different nuances.

Their initial intention, seemingly simple, "was the reform of the liturgy, which had begun with Pius XII," which had already reformed Holy Week; their second intention was ecclesiology; their third the Word of God, Revelation, and then also ecumenism. The French, much more than the Germans, he noted, still had the problem of dealing with the situation of the relationship between the Church and the world.

Referring to the reform of the liturgy, the Pope recalled that "after the First World War, a liturgical movement had grown in Western Central Europe," as "the rediscovery of the richness and depth of the liturgy," which hitherto was almost locked within the priest’s Roman Missal, while the people prayed with their prayer books "that were made according to the heart of the people," so that "the task was to translate the high content, the language of the classical liturgy, into more moving words, that were closer to the heart of the people. But they were almost two parallel liturgies: the priest with the altar servers, who celebrated the Mass according to the Missal, and the lay people who prayed the Mass with their prayer books.”

"Now," he continued, "the beauty, the depth, the Missal’s wealth of human and spiritual history" was rediscovered, as well as the need more than one representative of the people, a small altar boy, to respond "Et cum spiritu tuo" etc., to allow for "a real dialogue between priest and people," so that the liturgy of the altar and the liturgy of the people really were "one single liturgy, one active participation.

"And so it was that the liturgy was rediscovered, renewed."

The Pope said he saw the fact that the Council started with the liturgy as a very positive sign, because in this way "the primacy of God” was self-evident.

Some, he noted, criticized the Council because it spoke about many things, but not about God: instead, it spoke of God and its first act was to speak of God and open to the entire holy people the possibility of worshiping God, in the common celebration of the liturgy of the Body and Blood of Christ.

In this sense, he observed, beyond the practical factors that advised against immediately starting with controversial issues, it was actually "an act of Providence" that the Council began with the liturgy, God, Adoration.

The Holy Father then recalled the essential ideas of the Council: especially the paschal mystery as a center of Christian existence, and therefore of Christian life, as expressed in Easter and Sunday, which is always the day of the Resurrection, "over and over again we begin our time with the Resurrection, with an encounter with the Risen One."

In this sense, he observed, it is unfortunate that today, Sunday has been transformed into the end of the week, while it is the first day, it is the beginning: "inwardly we must bear in mind this is the beginning, the beginning of Creation, the beginning of the re-creation of the Church, our encounter with the Creator and with the Risen Christ."

The Pope stressed the importance of this dual content of Sunday: it is the first day, that is the feast of the Creation, as we believe in God the Creator, and an encounter with the Risen One who renews Creation: "its real purpose is to create a world which is a response to God's love. "

The Council also pondered the principals of the intelligibility of the Liturgy, instead of being locked up in an unknown language, which was no longer spoken, and active participation.

"Unfortunately," he said, "these principles were also poorly understood."

In fact, intelligibility does not mean "banalizing," because the great texts of the liturgy, even in the spoken languages, are not easily intelligible, he said. "They require an ongoing formation of the Christian, so that he may grow and enter deeper into the depths of the mystery, and thus comprehend."

And also concerning the Word of God, he asked, who can honestly say they understand the texts of Scripture, simply because they are in their own language?

"Only a permanent formation of the heart and mind can actually create intelligibility and participation which is more than one external activity, which is an entering of the person, of his or her being into communion with the Church and thus in fellowship with Christ," he said.

The Pope then addressed the second issue: the Church.

He recalled that the First Vatican Council was interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War and so had emphasized only the doctrine on primacy, which was described as "thanks to God at that historical moment" and "it was very much needed for the Church in the time that followed.”

But, he said, "it was just one element in a broader ecclesiology," already in preparation.

So a a fragment remained from the Council. So from the beginning, he said, the intention was to realise a more complete ecclesiology at a later time.

Here, too, he said, the conditions seemed very good, because after the First World War, the sense of Church was reborn in a new way.

A sense of the Church began to reawaken in people’s souls and the Protestant bishop spoke of the "century of the Church."

What was especially rediscovered from Vatican I, was the concept of the mystical body of Christ. The aim was to speak about and understand the Church not as an organization, something structural, legal, institutional, which it also is, but as an organism, a vital reality that enters my soul, so that I myself, with my own soul as a believer, am a constructive element of the Church as such. In this sense, Pius XII wrote the encyclical Mystici Corporis Christi, as a step towards a completion of the ecclesiology of Vatican I.

"I would say the theological discussion of the 1930s-1940s, even 1920s, was completely under the sign of the words Mystici Corporis," the Pope said.

"It was a discovery that created so much joy in this time and in this context the formula arose: 'We are the Church, the Church is not a structure, something ... we Christians, together, we are all the living body of the Church.'

"And of course this is true in the sense that we, the true ‘we’ of believers, along with the ‘I’ of Christ, the Church. Each one of us, not we, a group that claims to be the Church. No: this 'we are Church' requires my inclusion in the great 'we' of believers of all times and places.

So, the Pope said, this was the first idea: to complete the [Vatican I] ecclesiology in theological way, but progressing in a structural manner, that is, alongside the succession of Peter, his unique function, to even better define the function of the bishops of the episcopal body.

To do this, he said, the word "collegiality" was found, "which provoked great, intense and even – I would say – exaggerated discussions."

"But it was the word (it might have been another one), but this ord was needed to express that the bishops, together, are the continuation of the Twelve, the body of the Apostles.

"We said: only one bishop, that of Rome, is the successor of one particular apostle, Peter. All others become successors of the apostles entering the body that continues the body of the apostles. And just so the body of bishops, the college, is the continuation of the body of the Twelve, so it is necessary, it has its function, its rights and duties.

"It appeared to many," the Pope said, "as a struggle for power, and maybe some did think about power, but basically it was not about power, but the complementarity of the factors and the completeness of the body of the Church with the bishops, the successors the apostles as bearers, and each of them is a pillar of the Church together with this great body.”

"These," he continued, "were the two fundamental elements in the search for a comprehensive theological vision of ecclesiology. Meanwhile, after the 1940s, in the 1950s, a little criticism of the concept of the Body of Christ had already been born: 'mystical body,' some said, is too exclusive and risks overshadowing the concept of the 'people of God.' And the Council," he observed, "rightly, accepted this fact, which in the Fathers is considered an expression of the continuity between the Old and New Testaments. We Gentiles, we are not in and of ourselves the people of God, but we become the children of Abraham and therefore the people of God, by entering into communion with Christ who is the only seed of Abraham. And entering into communion with Him, being one with Him, we too are 'people of God.' That is, the concept of 'people of God' implies continuity of the Testaments, continuity of God's history in the world, with men, but also implies a Christological element. Only through Christology do we become the 'people of God,' and the two concepts are combined. And the Council," said the Pope, "decided to create a Trinitarian construction of ecclesiology: the People of God-the-Father-Body of Christ-Temple of the Holy Spirit.

"But only after the Council," he continued, "was an element that had been somewhat hidden, brought to light, even as early as the Council itself, that is, the link between the People of God, the (mystical) Body of Christ, and their communion with Christ, in the Eucharistic union.

"Here we become the body of Christ, that is, the relationship between the people of God and the Body of Christ creates a new reality, that is, the communion."

"And the Council," he continued, "led to the concept of communion as a central concept. I would say philologically that it had not yet fully matured in the Council, but it is the result of the Council that the concept of communion becomes more and more an expression of the sense of the Church, communion in different dimensions, communion with the Triune God, who Himself is communion between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, sacramental communion, concrete communion in the Episcopate and in the life of the Church.

"The problem of Revelation provoked even greater discussion: at issue was the relationship between Scripture and tradition, and above all this interested exegetes of a greater freedom, who felt somewhat, shall we say, in a situation of negativity before Protestants, who were making great discoveries, while Catholics felt a little 'handicapped' by the need to submit themselves to Magisterium. There was therefore a very concrete issue at stake: how free are exegetes? How does one read Scriptures well? What is meant by tradition?

"It was a pluri-dimensional battle that I can not outline now, but certainly what is important is that Scripture is the Word of God and the Church is subject to the Scriptures, obeys the Word of God, and is not above Scripture. Yet, Scripture is Scripture only because there is the living Church, its living subject; without the living subject of the Church Scripture is only a book, open to different interpretations, but which does not give any final clarity.

"Here, the battle, as I said, was difficult and the intervention of Pope Paul VI was decisive. This intervention shows all the delicacy of the Pope, his responsibility for the outcome of the Council, but also his great respect for the Council.

"The idea had emerged that Scripture is complete, everything can be found therein, so there was no need for tradition, and that Magisterium has nothing to say to us. Then the Pope sent the Council, I believe, 14 formulas of a sentence to be included in the text on Revelation and gave us, gave the Fathers, the freedom to choose one of 14 (formulas), but said: 'One has to be chosen to complete the text.'

"I remember, more or less, that the formula spoke of the Church's certainty of the faith not being based solely on a book, but needing the illuminated subject of the Church, guided by the Holy Spirit. Only in this way can Scripture speak and bring to bear all of its authority.

"We chose this phrase in the Doctrinal Commission, one of the 14 formulas. It is crucial, I think, to show the indispensability, the necessity of the Church, and to understand what tradition means, the living body in which the Word lives from the beginning and from which it receives its light, in which it was born.

"Because the simple fact of the Canon (the list of the books included in the Bible) is an ecclesial fact: that these writings are Scripture is the result of the illumination of the Church that found this canon of Scripture within herself, she found (this Canon), she did not make it, but found it. Only and always in this communion of the living Church can one really understand and read the Scriptures as the Word of God, as the Word that guides us in life and in death.

"As I said, this was a difficult discussion, but thanks to the Pope and thanks, let's say, to the light of the Holy Spirit who was present at the Council, a document that is one of the most beautiful and also innovative of the whole Council was created, which demands further study, because even today exegesis tends to read Scripture outside of the Church, outside of faith, only in the so-called spirit of the historical-critical method — an important method, but never able to give solutions as a final certainty (which comes) only if we believe that these are not human words: they are the words of God. And only if (we), the living subjects to whom God has spoken, to whom God speaks, are alive, can we correctly interpret Sacred Scripture.

"And there is still much to be done, as I said in the preface of my book on Jesus, to arrive at a reading of Scripture that is really in the spirit of the Council. Here the application of the Council is not yet complete, it has yet to be accomplished.

"Finally, ecumenism. I do not want to enter into these problems, but it was obvious, especially after the suffering of Christians in the time of National Socialism, that Christians could find unity, at least seek unity, but also that only God can give unity. We are still on this journey.

"Now, with these issues, the Rhine alliance, so to speak, had done its work: the second part of the Council is much broader.

"Now the themes of 'the world today,' 'the modern era and the Church,' emerged with greater urgency, and with them, the themes of responsibility for the building of this world, society’s responsibility for the future of this world and eschatological hope, the ethical responsibility of Christians, where they find their guides, and then religious freedom, progress and all that, and relations with other religions.

"Now all the players in the Council really entered into discussions, not only the Americas-United States with a strong interest in religious freedom. In the third session they told the Pope: 'We cannot go home without bringing with us a declaration on religious freedom passed by the Council.'

"The Pope [Paul VI], however, had firmness and decision, the patience to delay the text until the fourth session, to reach a maturation and a fairly complete consensus among the Fathers of the Council.

"I say, not only the Americans had now entered with great force into the Council arena, but also Latin America, knowing full well the misery of their people, a Catholic continent and their responsibility for the situation of the faith of these people.

"And Africa, Asia, also saw the need for interreligious dialogue: increased problems that we Germans, I must say, at the beginning had not seen. I cannot go into greater depth on this now.

"The great document Gaudium et Spes describes very well the problem analyzed between Christian eschatology and worldly progress, between our responsibility for the society of tomorrow and the responsibility of the Christian before eternity, and so it also renewed Christian ethics, the foundations.

"But unexpectedly, a document that responded in a more synthetic and concrete manner to the great challenges of the time, took shape outside of this great document, namely Nostra Aetate.

"From the beginning, there were our Jewish friends, who said to us Germans especially, but not only to us, that after the sad events of this century, this decade of National Socialism, the Catholic Church had to say a word on the Old Testament, the Jewish people. They also said 'it was clear that the Church is not responsible for the Shoah. Those who have committed these crimes were Christians, for the most part, we must deepen and renew the Christian conscience, even if we know that the true believers always resisted these things.' [Note: I believe these lines of the Vatican Radio transcription need to be checked against the Pope's actual words in his talk, which I am unable to access at this time.]

"And so, it was clear that we had to reflect on our relationship with the world of the ancient people of God. We also understood that the Arab countries, the bishops of the Arab countries, were not happy with this. They feared a glorification of the State of Israel, which they did not want to, of course. They said, 'Well, a truly theological indication on the Jewish people is good, it is necessary, but if you are to speak about this, you must also speak of Islam. Only in this way can we be balanced. Islam is also a great challenge and the Church should clarify its relationship with Islam.' This is something that we didn’t really understand at the time, a little, but not much. Today we know how necessary it was.

"And when we started to work also on Islam, they said: 'But there are also other religions of the world: all of Asia! Think about Buddhism, Hinduism...'

"And so, instead of an initial declaration originally meant only for the ancient people of God, a text on interreligious dialogue was created anticipating by 30 years what would later reveal itself in all of its intensity and importance. I can not enter into it now, but if you read the text, you see that it is very dense and prepared by people who really knew the truth, and it briefly indicates, in a few words, what is essential. Thus also the foundations of a dialogue in diversity, in faith to the uniqueness of Christ, who is One.

"It is not possible for a believer to think that religions are all variations on a theme of 'no.'

"There is a reality of the living God who has spoken, and is a God, a God incarnate, therefore the Word of God is really the Word of God.

"But there is religious experience, with a certain human light of creation, and therefore it is necessary and possible to enter into dialogue and thus open up to each other and open all peoples up to the peace of God, of all his children, and his entire family.

"Thus, these two documents, religious freedom and Nostra Aetate associated with Gaudium et Spes are a very important trilogy, the importance of which has only been revealed over the decades, and we are still working to understand this uniqueness of the revelation of God, uniqueness of God incarnate in Christ and the multiplicity of religions with which we seek peace and also an open heart to the light of the Holy Spirit who enlightens and guides to Christ.

"I would now like to add yet a third point: there was the Council of the Fathers, the true Council, but there was also the Council of the media. It was almost a Council in and of itself, and the world perceived the Council through them, through the media.

"So the immediate message of the Council that got thorough to the people, was that of the media, not that of the Fathers.

"And while the Council of the Fathers evolved within the faith, it was a Council of the faith that sought the intellectus, that sought to understand, to try to understand the signs of God at that moment, that tried to meet the challenge of God in this time to find the words for today and tomorrow.

"So while the whole Council, as I said, moved within the faith, as fides quaerens intellectum, the Council of journalists did not, naturally, take place within the world of faith, but within the categories of the media of today, that is outside of the faith, with different hermeneutics.

"It was a hermeneutic of politics.

"The media saw the Council as a political struggle, a struggle for power between different currents within the Church. It was obvious that the media would take the side of whatever faction best suited their world.

"There were those who sought a decentralization of the Church, power for the bishops and then, through the Word for the 'People of God,' the power of the people, the laity.

"There was this triple issue: the power of the Pope, then transferred to the power of the bishops, and then the power of all... popular sovereignty.

"Naturally they saw this as the part to be approved, to promulgate, to help.

"This was the case for the liturgy: there was no interest in the liturgy as an act of faith, but as a something to be made understandable, similar to a community activity, something profane. And we know that there was a trend, which was also historically based, that said: 'Sacredness is a pagan thing, possibly even from the Old Testament. In the New Testament the only important thing is that Christ died outside: that is, outside the gates, that is, in the secular world.'

"Sacredness ended up as profanity even in worship: worship is not worship but an act that brings people together, communal participation and thus participation as activity.

"And these translations, trivializing the idea of the Council, were virulent in the practice of implementing the liturgical reform, born in a vision of the Council outside of its own key vision of faith.

"And it was so, also in the matter of Scripture: Scripture is a book, historical, to treat historically and nothing else, and so on.

"And we know that this Council of the media was accessible to all. So, dominant, more efficient, this Council created many calamities, so many problems, so much misery, in reality: seminaries closed, convents closed liturgy trivialized... and the true Council has struggled to materialize, to be realized: the virtual Council was stronger than the real Council.

"But the real strength of the Council was present and slowly it has emerged and is becoming the real power which is also true reform, true renewal of the Church.

"It seems to me that 50 years after the Council, we see how this Virtual Council is breaking down, getting lost and the true Council is emerging with all its spiritual strength.

"And it is our task, in this Year of Faith, starting from this Year of Faith, to work so that the true Council with the power of the Holy Spirit is realized and Church is really renewed.

"We hope that the Lord will help us. I, retired in prayer, will always be with you, and together we will move ahead with the Lord in certainty. The Lord is victorious. Thank you."