SCHISM: TRIUMPH OF FAITH OR FAILURE OF LOVE?

![Related image]()

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

BEFORE THE CREED IN THE BYZANTINE LITURGY

Back around 1964, at the suggestion of one of my professors, I attended the "Semaine Liturgique" at the Institut Saint-Serge in Paris. One of the interesting people I met was an old ex-Jesuit who was an expert in Syrian Christianity. He invited me to his home which was a Syrian chaplaincy, and I concelebrated at the Divine Liturgy there, following an English translation, while he celebrated in Aramaic. He told me about what happened the day he joined the Jesuits.

He arrived, an eager teenager, at the door of the Jesuit noviceship at the same moment as another boy whose name was Henri de Lubach. They put their suitcases down in the hall and waited for someone to show them their rooms. On the wall was a large chart called "The Triumphs of the Church", with a list of such triumphs down the centuries. It began "The Church triumphs over Arianism, the Council of Nicaea, 325AD; the Church triumphs over Nestorianism, the Council Ephesus, 449AD;" and continued right down to "The Church triumphs over Protestantism, Council of Trent, 1545 to 1563" and, "The Church triumphs over Modernism, Pius X, Pascendi, 1907." The two youths looked at the list for a time, and then Henri de Lubach turned to his companion and said, "One more triumph like these and we shall have nobody left!"

BEFORE THE CREED IN THE BYZANTINE LITURGY

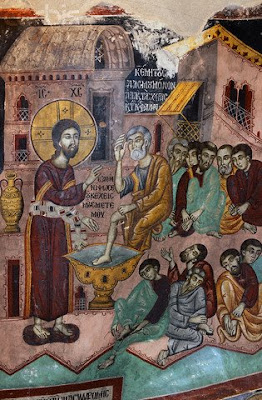

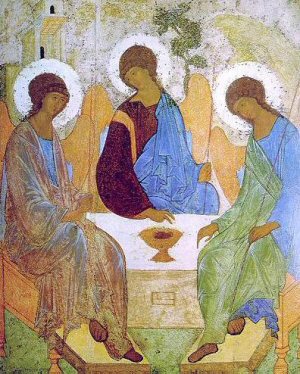

Just before the Eucharistic Prayer and after commemorating the Communion of Saints comes the Creed, sung by all. The Celebrant says:

"Peace to you all".

and they reply:

"And to your Spirit".

the Celebrant:

"Let us love one another, so that with one mind we may confess out faith",

the choir:

"In the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, the consubstantial and undivided Trinity".

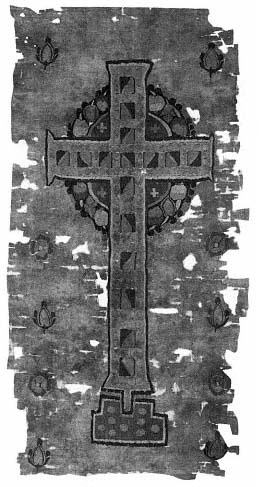

Then comes the creed, and, while it is being sung, the celebrants wave the chalice veil over the gifts. (See the photo at the top of this post.) In one symbolic gesture, the Church emphasises a) the coming of the Holy Spirit whose love for the Church we share in our own mutual love, b) our common understanding of the faith that is the fruit of our mutual love as we understand together, and c) the consecration of the bread and wine in which we are about to share.

This teaching from Catholic/Orthodox Tradition is expressed by the Romanian Patriarchate when it speaks about the controversy surrounding the Orthodox council in Crete in 2016:

This raises the question, Can mutual antagonism or even lack of mutual love and trust be sufficient causes to result in schism and accusations of heresy? Can a schism which is hailed as the triumph of truth over error be rooted in a rather grubby failure to love one another as Christ has loved us?

This question must bear in mind that Catholic Tradition has its origins in the Eucharistic communities whose chief characteristic is the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church by which the Word is preached, the sacraments are confected and, centrally, the Eucharist is celebrated. As the history of the local church from the time of the Apostles till now is reflected in its liturgy and its understanding of the faith, Tradition is pluriform in its origins. However, as Word and Eucharist are identical in every celebration, not withstanding the differences in form and culture, so each local church is identical to all others in that each and all are the one body of Christ. It is safe to say, Where the Eucharist is, there is the Church. The one guarantee that each church is authentically the same as the rest is mutual recognition by the rest.

We shall look briefly at three occasions in which I think it can be demonstrated that lack of love played its proper part in bringing about schism or deepening schism where it already exists.

Let us examine the Nestorian Schism and the Assyrian Church of the East, the Monophysite Schism and the Coptic Church, and the case of the papacy and Orthodoxy. These will be nothing more than skeleton arguments and shall leave much unsaid.

There are three major divisions is apostolic Christianity, the Oriental Orthodox, the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholicism. One great historic difference between them is their relationship or lack of it to the Byzantine Empire: the Assyrian Church belonged to the rival Persian Empire and was not invited to the ecumenical councils; the Copts belonged to the Byzantine Empire but wanted independence; while the Latins looked at the Roman Empire with nostalgia but the Byzantine emperors were too weak to function in the West so that the western peoples had to look to themselves. The other great difference was cultural. The Oriental Orthodox were strongly influenced even in apostolic times by Jewish converts to Christianity and, especially in Syria and Ethiopia, it can be said that their Christianity is semitic in form. The Assyrians and Syrian Orthodox have their liturgy in Aramaic, the language of Our Lord. They also have their classical theological texts in the form of stories, hymns, poems as well as homilies and other texts. In contrast, the Orthodox are heir to Greek abstract thought, to Socrates and Plato and the Greek Fathers. The Latins, living within a kind of chaos, put much emphasis to

Its rival for dominance in that part of the Empire was Alexandria, the source of grain for the whole Byzantine Empire, and also was the cultural centre of the civilised world, famous for its intellectual life and philosophical thought. This philosophical sophistication is reflected in its christology.

The Church in Persia was steeped in Jewish biblical thought, and their theological way of teaching in their school in Edessa was for the teacher to read a passage of Scripture while the students wrote down their interpretation. Until the middle of the fifth century, their main model and book of reference was St Ephrem; but, as he only translated and commented on a part of the Bible, they translated the complete works of St Theodore of Mopsuestia who commented on Scripture in the same way as they did, as near to the literal meaning as possible Theodore of Mopsuestia became the main interpreter of the Church in Persia. Here is Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev's interpretation of Theodore's christology:

John Grantham, delegate at German Old Catholic synod since 2007, parish council member in Berlin, raised Anglican/Episcopal

Written 12 Jan 2015

There is no easy answer to this, but it has to do with possibly differing Christological views regarding the two natures of Christ. Historically the Assyrians were accused by both Rome and Orthodoxy of Nestorianism, but the Assyrians themselves have claimed that that is not true, and it is not even historically certain what exactly Nestorius taught.

What Rome and the Orthodox claimed was that Nestorius (and with him the Assyrian Church) denied the full and complete union of Christ’s human and divine natures, the Hypostatic union that is considered dogma by all Chalcedonian churches (which includes Rome, most Western Christians, and the Orthodox). While it is true that Nestorius refused to use the title Theotokos or “God-Bearer” for Mary, it is by no means certain that that is the reason why.

The Assyrians then went into schism amongst themselves after 1552, with one branch joining the Roman Catholic communion, and the other remaining independent. That independent part is what is now known as the Assyrian Church of the East.

The Assyrian Church, meanwhile, explicitly denied that they followed Nestorius’ teachings as recently as 1976, and there has been an ongoing rapprochement between them and other churches since at least the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. It may well be that the schism between the Assyrians and other churches was all a major misunderstanding, or it may be that the Assyrians gradually came to adopt the same views as the Orthodox and Rome. Hard to say for sure.

* Qnuma, is an Aramaic word. The nearest equivalent is the Greek “hypostasis” in Latin “substantia” and in English “substance”.

II - THE ORIENTAL ORTHODOX WHO REFUSED TO ACCEPT THE COUNCIL OF CHALCEDON (451)

Furthermore, in the Coptic

Encyclopedia, W.H.C. Frend defines monophystism as a doctrine:

Metropolitan Hilarion continues to treat the tradition of St Cyril of Alexandria:

Why did the East Syrians reject Ephesus? Here is Metropolitan Hilarion again:

Then came the Council of Chalcedon that was accepted neither by the Church of the East nor the Church of Alexandria, but did integrate both the alexandrine and the antiochene traditions into one single Tradition in the Catholic/Orthodox Church.

Why did the Oriental Orthodox churches reject Chalcedon?

Politics - Emperor Marcian was supporting the Tome of Leo upon which the definition of Chalcedon is based, while the Egyptians were against the emperor. (Those who were in favour of Chalcedon were called "kings men" or "Melkites", not "pope's men", even though they were supporting Pope Leo's Tome.) Pope Leo was also very active in support of the primacy of the Holy See.

2. Their hostility to the antiochene position made them refuse to acknowledge the formula "Two distinct natures", specially as Nestorius agreed with the formula.

3. Loyalty to the "mia physis" formula they had received from St Athanasius.

Why did the Assyrian Church of the East reject Chalcedon?

It was impossible to translate the Chalcedonian formula from Greek into Syriac. Metropolitan Hilarion puts it this way:

In Syriac the Chalcedonian formula did not make sense!

COMMON CHRISTOLOGICAL DECLARATION

COMMON DECLARATION

Tower of St. John in the Vatican gardens

Paul VI, bishop of Rome and Pope of the Catholic Church, and Shenouda III, Pope of Alexandria and patriarch of the See of St. Mark, give thanks in the Holy Spirit to God that, after the great event of the return of relics of St. Mark to Egypt, relations have further developed between the Churches of Rome and Alexandria so that they have now been able to meet personally together. At the end of their meetings and conversations they wish to state together the following:

We have met in the desire to deepen the relations between our Churches and to find concrete ways to overcome the obstacles in the way of our real cooperation in the service of our Lord Jesus Christ who has given us the ministry of reconciliation, to reconcile the world to Himself (2 Cor 5:18-20).

In accordance with our apostolic traditions transmitted to our Churches and preserved therein, and in conformity with the early three ecumenical councils, we confess one faith in the One Triune God, the divinity of the Only Begotten Son of God, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, the Word of God, the effulgence of His glory and the express image of His substance, who for us was incarnate, assuming for Himself a real body with a rational soul, and who shared with us our humanity but without sin. We confess that our Lord and God and Saviour and King of us all, Jesus Christ, is perfect God with respect to His Divinity, perfect man with respect to His humanity. In Him His divinity is united with His humanity in a real, perfect union without mingling, without commixtion, without confusion, without alteration, without division, without separation. His divinity did not separate from His humanity for an instant, not for the twinkling of an eye. He who is God eternal and invisible became visible in the flesh, and took upon Himself the form of a servant. In Him are preserved all the properties of the divinity and all the properties of the humanity, together in a real, perfect, indivisible and inseparable union.

The divine life is given to us and is nourished in us through the seven sacraments of Christ in His Church: Baptism, Chrism (Confirmation), Holy Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Matrimony and Holy Orders.

We venerate the Virgin Mary, Mother of the True Light, and we confess that she is ever Virgin, the God- bearer. She intercedes for us, and, as the Theotokos, excels in her dignity all angelic hosts.

We have, to a large degree, the same understanding of the Church, founded upon the Apostles, and of the important role of ecumenical and local councils. Our spirituality is well and profoundly expressed in our rituals and in the Liturgy of the Mass which comprises the centre of our public prayer and the culmination of our in corporation into Christ in His Church. We keep the fasts and feasts of our faith. We venerate the relics of the saints and ask the intercession of the angels and of the saints, the living and the departed. These compose a cloud of witnesses in the Church. They and we look in hope for the Second Coming of our Lord when His glory will be revealed to judge the living and the dead.

We humbly recognize that our Churches are not able to give more perfect witness to this new life in Christ because of existing divisions which have behind them centuries of difficult history. In fact, since the year 451 A.D., theological differences, nourished and widened by non-theological factors, have sprung up. These differences cannot be ignored. In spite of them, however, weare rediscovering ourselves as Churches witha common inheritance and are reaching out with determination and confidence in the Lord to achieve the fullness and perfection of that unity which is His gift.

As an aid to accomplishing this task, we are setting up a joint commission representing our Churches, whose function will be to guide common study in the fields of Church tradition, patristics, liturgy, theology, history and practical problems, so that by cooperation in common we may seek to resolve, in a spirit of mutual respect, the differences existing between our Churches and be able to proclaim together the Gospel in ways which correspond to the authentic message of the Lord and to the needs and hopes of todayss world. Atthe same time we express our gratitude and encouragement to other groups of Catholic and Orthodox scholars and pastors who devote their efforts to common activity in these and related fields.

With sincerity and urgency we recall that true charity, rooted in total fidelity to the one Lord Jesus Christ and in mutual respect for each oness traditions, is an essential element of this search for perfect communion.

In the name of this charity, we reject all forms of proselytism, in the sense of acts by which persons seek to disturb each other's communities by recruiting new members from each other through methods, or because of attitudes of mind, which are opposed to the exigencies of Christian love or to what should characterize the relationships between Churches. Let it cease, where it may exist. Catholics and Orthodox should strive to deepen charity and cultivate mutual consultation, reflection and cooperation in the social and intellectual fields and should humble themselves before God, supplicating Him who, as He has begun this work in us, will bring it to fruition.

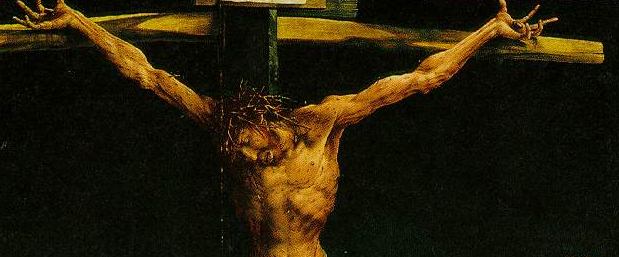

As we rejoice in the Lord who has granted us the blessings of this meeting, our thoughts reach out to the thousands of suffering and homeless Palestinian people. We deplore any misuse of religious arguments for political purposes in this area. We earnestly desire and look for a just solution for the Middle East crisis so that true peace with justice should prevail, especially in that land which was hallowed by the preaching, death and resurrection of our Lord and Saviour Jusus Christ, and by the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, whom we venerate together as the Theotokos. May God, the giver of all good gifts, hear our prayers and bless our endeavours.

From the Vatican, May 10, 1973.

Two churches of apostolic origin, each with its own tradition that springs from the synergy between the Holy Spirit and their ecclesial life as eucharistic community down the ages and shaped by its culture and its historical circumstances. The Assyrian Church of the East has a semitic culture and is isolated from the church of the Roman Empire because it has grown up in the Persian Empire and did not get invited to ecumenical councils. Alexandria is an intellectual hub of Eastern Christianity, supplier of grain to the Empire, yet wanting independence from the Greeks. The two traditions clash, each considering the other to be heretical. They are both regional versions of the Christian faith that cannot recognise one another. The language of both sides are, perhaps, inadequate, the Antiochene expression of the Incarnation leading some to suppose that the unity of the two natures is in our own minds rather than in the Incarnation itself, while the Alexandrine tradition led some to believe that, for them, divinity and humanity are somehow mixed into a single divine-human nature. Yet both traditions are the fruit of a single eucharistic life, both churches daily invoked the same Holy Spirit, and, many centuries later, both churches could sign a common declaration of faith with the Holy See on a subject that had previously bitterly divided them from each other and from Catholic communion.

I believe this has much to teach us about the other divisions in Christendom and may indicate the way to resolve them.

John 6, 55 - 57

John 17, 21 - 23

Christ is the source of the Church and we are Christians because Christ lives in us and we in him. This is the basic Christianity, not our version of it but Christ's.

Where the Eucharist is, there is the Church because it is in the Eucharist that we receive his body and blood in such a way that we are in him and he in us: we are the body of Christ. The Catechism says:

There is only one Mass in which Christ is priest, victim and altar. As St John Chrysostom said, just God said, "Let there be light," and this command from eternity resonates for ever throughout creation, so Jesus said, "This is my body...This is the chalice of my blood," and this becomes true at every Mass. There is only one Eucharist, so that the priest celebrates in persona Christi because Christ is the celebrant at all masses as we approach the heavenly tabernacle, and all who participate in one Mass also participate spiritually at every other Mass, across time and space, and even across the things that divide us. Ignorant Orthodox monks may call the pope "anti-Christ", but they share the body and blood of Christ with him every time they take part in the Divine Liturgy. The whole of God's Church is visibly present through every local congregation.

The liturgy is always the work of the local church, and it the source of all the Church's powers, as Sacrosanctum Concilium tells us:

Some opponents of this understanding of the Church accuse us of adopting the Anglican branch theory, but this is not true either historically nor theologically.

Historically, the origin is Russian Orthodox. Metropolitan John Zizioulas says that the importance of the local church given in Vatican II

Does that mean that we should forget all that divides us, and just come together. Unfortunately, it isn't that simple. Being united to one another implies, not only being one with our neighbour, but also across time. We owe our very existence as churches to the passing, from one generation to the next, of the apostolic tradition in the form it has come down to us. Becoming one with our neighbour in the present involves reconciling our traditions one with the other, as we have seen taking place between our Assyrian and Coptic brethren. In that way, the Catholic life of the whole Church will be deepened and enriched. To ignore the past in favour of a modern but rootless unity may be legitimate for some Protestant communities, but it would be a denial of our very being as Apostolic churches.

We are already one with all who have encountered Jesus, all who dwell in him and he in them. Even if they are Protestants and know nothing of the Mass, they are connected with the Mass by their faith in Christ, and we are present in the Mass for them as well as for ourselves. Let our apostolate be an outreach of love that reflects the love of God for all.

This teaching from Catholic/Orthodox Tradition is expressed by the Romanian Patriarchate when it speaks about the controversy surrounding the Orthodox council in Crete in 2016:

Any explanation regarding the exposition of Orthodox faith must be given within ecclesial communion, not in a state of rebellion and disunion, because the Holy Spirit is, at the same time, the Spirit of Truth (cf. John 16:13) and the Spirit of fellowship or communion (cf. 2 Corinthians 13:13).

This raises the question, Can mutual antagonism or even lack of mutual love and trust be sufficient causes to result in schism and accusations of heresy? Can a schism which is hailed as the triumph of truth over error be rooted in a rather grubby failure to love one another as Christ has loved us?

This question must bear in mind that Catholic Tradition has its origins in the Eucharistic communities whose chief characteristic is the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church by which the Word is preached, the sacraments are confected and, centrally, the Eucharist is celebrated. As the history of the local church from the time of the Apostles till now is reflected in its liturgy and its understanding of the faith, Tradition is pluriform in its origins. However, as Word and Eucharist are identical in every celebration, not withstanding the differences in form and culture, so each local church is identical to all others in that each and all are the one body of Christ. It is safe to say, Where the Eucharist is, there is the Church. The one guarantee that each church is authentically the same as the rest is mutual recognition by the rest.

We shall look briefly at three occasions in which I think it can be demonstrated that lack of love played its proper part in bringing about schism or deepening schism where it already exists.

Let us examine the Nestorian Schism and the Assyrian Church of the East, the Monophysite Schism and the Coptic Church, and the case of the papacy and Orthodoxy. These will be nothing more than skeleton arguments and shall leave much unsaid.

There are three major divisions is apostolic Christianity, the Oriental Orthodox, the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholicism. One great historic difference between them is their relationship or lack of it to the Byzantine Empire: the Assyrian Church belonged to the rival Persian Empire and was not invited to the ecumenical councils; the Copts belonged to the Byzantine Empire but wanted independence; while the Latins looked at the Roman Empire with nostalgia but the Byzantine emperors were too weak to function in the West so that the western peoples had to look to themselves. The other great difference was cultural. The Oriental Orthodox were strongly influenced even in apostolic times by Jewish converts to Christianity and, especially in Syria and Ethiopia, it can be said that their Christianity is semitic in form. The Assyrians and Syrian Orthodox have their liturgy in Aramaic, the language of Our Lord. They also have their classical theological texts in the form of stories, hymns, poems as well as homilies and other texts. In contrast, the Orthodox are heir to Greek abstract thought, to Socrates and Plato and the Greek Fathers. The Latins, living within a kind of chaos, put much emphasis to

I - The Nestorian Schism and the Assyrian Church in the East.

The Syriac Tradition in Christianity

Dr Sebastian Brock of Oxford

"3. In spite of the coming of so many westerners (Greek Nestorians), who were in exile, the Church of the East remained a Semitic, Syriac, non-Gentile Church. It retained its ancient forms of worship; it did not alter its doctrine; it continued to pursue its long established goals."

- Assyrian ForumWe must bear in mind that the Assyrian Church of the East that rejected the councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451) was situated in the Persian Empire and not in the Byzantine Empire. As invitations to attend the early ecumenical councils were made by the Roman emperor in Byzantium and sent only to the bishops of his empire, the Assyrian Church was never invited. It accepted the decisions of the Council of Nicaea (325), but only 85 years after it met. Another important point is that they spoke Syriac, a version of Aramaic, the language of Our Lord, and not Greek. Their liturgy was and is in Aramaic, and it could be argued that, along with other Oriental Orthodox, they are the true successors of the very first Jewish converts; they are the voice of semitic christianity. Ancient Syria was divided by the two empires, with Antioch, the religious capital both for Hellenistic Jews and Christians, being within the Byzantine Empire. It was where followers of Christ were first called Christians and, beside becoming one of the five main patriarchates of the universal Church, it was also one of the two leading schools of theology, the other being Alexandria. Thus, while the parts of Syria that was under Persian rule, that are now in Iran and Iraq - modern Mosul is ancient Nineveh, were largely cut off from life in the Byzantine Empire, the main part, centred on Antioch (now in modern Turkey), was, in contrast, a very important centre.

Its rival for dominance in that part of the Empire was Alexandria, the source of grain for the whole Byzantine Empire, and also was the cultural centre of the civilised world, famous for its intellectual life and philosophical thought. This philosophical sophistication is reflected in its christology.

The Church in Persia was steeped in Jewish biblical thought, and their theological way of teaching in their school in Edessa was for the teacher to read a passage of Scripture while the students wrote down their interpretation. Until the middle of the fifth century, their main model and book of reference was St Ephrem; but, as he only translated and commented on a part of the Bible, they translated the complete works of St Theodore of Mopsuestia who commented on Scripture in the same way as they did, as near to the literal meaning as possible Theodore of Mopsuestia became the main interpreter of the Church in Persia. Here is Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev's interpretation of Theodore's christology:

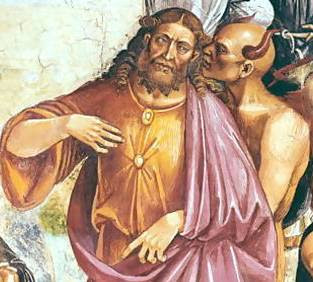

Theodore made a sharp distinction between Jesus the man and the Word of God, speaking of the "inhabitation" of the Word of God in Jesus as in the "temple"...representatives of the antiochene school, Diodore of Tarsus, Theodore of Mopsuestia and Nestorius of Constantinople, suggested the following terminological expression ofthe unity of the two natures: God the Word 'assumed' the man Jesus; the unbegotten Word of God 'inhabited' the one who was born of Mary; the Word 'dwelt' in the man as in the 'temple'; the Word put on the human nature as a 'garment'. The man Jesus was united to the Word and assumed divine dignity. When asked the question, "Who suffered on the Cross?" they would answer, "The flesh of Christ", "the humanity of Christ", his "human nature", or "the things human". Thus they drew a sharp line between the divine and human natures of Christ. During the earthly life of Jesus both natures preserved their characteristics, so if one speaks of the unity of the two natures, this unity is mental rather than ontological: it exists in our understanding of Christ, in our worship of him; we unite both natures and venerate on Christ, God and man. (my source: The Spiritual World of Isaac the Syrian, Introduction, page 18)

On what beliefs and doctrines does the Assyrian Church of the East differ from Eastern Orthodoxy?

1 AnswerJohn Grantham, delegate at German Old Catholic synod since 2007, parish council member in Berlin, raised Anglican/Episcopal

Written 12 Jan 2015

There is no easy answer to this, but it has to do with possibly differing Christological views regarding the two natures of Christ. Historically the Assyrians were accused by both Rome and Orthodoxy of Nestorianism, but the Assyrians themselves have claimed that that is not true, and it is not even historically certain what exactly Nestorius taught.

What Rome and the Orthodox claimed was that Nestorius (and with him the Assyrian Church) denied the full and complete union of Christ’s human and divine natures, the Hypostatic union that is considered dogma by all Chalcedonian churches (which includes Rome, most Western Christians, and the Orthodox). While it is true that Nestorius refused to use the title Theotokos or “God-Bearer” for Mary, it is by no means certain that that is the reason why.

The Assyrians then went into schism amongst themselves after 1552, with one branch joining the Roman Catholic communion, and the other remaining independent. That independent part is what is now known as the Assyrian Church of the East.

The Assyrian Church, meanwhile, explicitly denied that they followed Nestorius’ teachings as recently as 1976, and there has been an ongoing rapprochement between them and other churches since at least the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. It may well be that the schism between the Assyrians and other churches was all a major misunderstanding, or it may be that the Assyrians gradually came to adopt the same views as the Orthodox and Rome. Hard to say for sure.

A MODERN DECLARATION OF FAITH

We believe in one God the Father, the Omnipotent, the Maker of all things visible and invisible. We believe in one Lord Jesus Christ the Son of God; the Only-Begotten and the Firstborn of all creatures. He who was born of His Father eternally before all worlds and was not created, true God from true God, of the same nature of His Father, by whom the worlds were made and all things were created, who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and became Man. He was conceived and born of the Virgin Mary; He suffered and was crucified in the days of Pontius Pilate, and was buried and rose on the third day as it is written, and ascended into heaven and sat down at the right hand of His Father; He shall come again to judge the dead and the living. We profess two natures in our Lord Jesus Christ, namely that He is fully God and fully Man, and in two Qnome* everlastingly and inseparably united in the one person of Sonship. We profess that the Virgin Mary is the Mother of our Lord Jesus Christ, who gave birth to the one Son of God become Man.

The Theology of the Church of the East has been stated briefly and clearly in the following Hymn of Teshbokhta

Composed by Mar Babai the Great in the sixth century A.D.

a noted theologian of the Church

One is Christ the Son of God,

Worshiped by all in two natures;

In His Godhead begotten of the Father,

Without beginning before all time;

In His humanity born of Mary,

In the fullness of time, in a body united;

Neither His Godhead is of the nature of the mother,

Nor His humanity of the nature of the Father;

The natures are preserved in their Qnumas*,

In one person of one Sonship.

And as the Godhead is

three substances in one nature,

Likewise the Sonship of the Son is

in two natures, one person.

So the Holy Church has learnt,

to confess the Son, who is Christ.

* Qnuma, is an Aramaic word. The nearest equivalent is the Greek “hypostasis” in Latin “substantia” and in English “substance”.

[We shall see how it is so easy to misunderstand once we translate from one language to another. In classical Christian vocabulary, "hypostasis" means "person" and not "substance", so that "the natures are preserved in their "gnumas"" can mean that in Christ there are two persons!]

II - THE ORIENTAL ORTHODOX WHO REFUSED TO ACCEPT THE COUNCIL OF CHALCEDON (451)

Oriental Orthodoxy, also known by several other names is a communion of Eastern Christian churches that recognize only the first three ecumenical councils – the First Council of Nicaea in 325, the First Council of Constantinople in 381 and the Council of Ephesus in 431.[5] This communion is composed of six autocephalous churches: the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.[6] Oriental Orthodoxy has approximately 84 million adherents worldwide.Oriental Orthodox Churches uphold their own ancient ecclesiastic traditions of apostolic succession and catholicity (universal doctrine).These Churches rejected the definition of the two natures of Christ (human and divine), known as the Chalcedonian Definition, which was issued by the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Over the following two centuries, one by one, they discontinued their communion with the Great Church, and developed separate institutions that did not participate in any of the later ecumenical councils.

Furthermore, in the Coptic

Encyclopedia, W.H.C. Frend defines monophystism as a doctrine:

opposed to the orthodox doctrine that He (Christ) is one person and has two natures..... The monophysites hold.... that the two natures of Christ were united at the Incarnation in such a way that the one Christ was essentially divine although He assumed from the Virgin Theotokos the flesh and attributes of man

EPHESUS AND CHALCEDON

All quotations from Metropolitan Alfeyev are from the Introduction of his "The Spiritual world of Isaac the Syrian"

The alexandrine tradition which, in the person of Cyril of Alexandria, was in conflict with Nestorius, opposed to the antiochene tradition another understanding of the unity of the two natures: the Word became human and did not merely assume human nature; the unbegotten Word of God is the same person as Jesus born from Mary; therefore it was God, the Word himself who 'suffered in the flesh' ( epathan saki). Thus there is one Son, one hypostasis, 'one nature of God, the Word incarnate' (mia physis to theou logou sesarkomene). The latter phrase, which belonged to Apollinaris of Laodicaea, cast the suspicion of 'mixture' and 'confusion' of the two natures on Cyril of Alexandria. Cyril's Christology was confirmed by the Council of Ephesus 431 but rejected by the east-syrian theological tradition, which remained faithful to the christological terminology of Theodore and Diodore.

Why did the East Syrians reject Ephesus? Here is Metropolitan Hilarion again:

Why did the east-syrian tradition not accept the Council of Ephesus? The answer is not concealed in the personality of Nestorius- he was barely known in Persia even by name until the sixth century- but in the procedures of the Council. The Church of Persia did not accept the Council mainly because it was conducted by Cyril of Alexandria and his adherents in the absence of John of Antioch who, upon his arrival to Ephesus, anathematized Cyril. The christological position of Ephesus was purely alexandrian: it took no account of the antiochene position, and it was precisely the antiochene (and not 'nestorian') Christology that was the Christology of the Church of the East.

Then came the Council of Chalcedon that was accepted neither by the Church of the East nor the Church of Alexandria, but did integrate both the alexandrine and the antiochene traditions into one single Tradition in the Catholic/Orthodox Church.

Why did the Oriental Orthodox churches reject Chalcedon?

The majority of the bishops who attended the Council of Chalcedon, as scholars indicate, believed that the traditional formula of faith received from St. Athanasius was the "one nature of the Word of God." This belief is totally different from the Eutychian concept of thesingle nature (i.e. Monophysite). The Alexandrian theology was by no means docetic. Neither was it Apollinarian, as stated clearly. It seems that the main problem of the Christological formula was the divergent interpretationof the issue between the Alexandrian and the Antiochian theology. While Antioch formulated its Christology against Apollinarius and Eutyches, Alexandria did against Arius and Nestorius. At Chalcedon, Dioscorus refused to affirm the "in two natures" and insisted on the "from two natures." Evidently the two conflicting traditions had not discovered an agreed theological standpoint between them.

"Mia Physis"

The Church of Alexandria considered as central the Christological mia physis formula of St. Cyril one incarnate nature of God the Word". The Cyrillian formula was accepted by the Council of Ephesus in 431. It was neither nullified by the Reunion of 433, nor condemned at Chalcedon. On the contrary, it continued to be considered an orthodox formula. Now what do the non-Chalcedonians mean by the mia physis, the "one incarnate nature?". They mean by mia one, but not "single one" or "simple numerical one," as some scholars believe. There is a slight difference between mono and mia. While the former suggests one single (divine) nature, the latter refers to one composite and united nature, as reflected by the Cyrillian formula. St. Cyril maintained that the relationship between the divine and the human in Christ, as Meyendorff puts it, "does not consist of a simple cooperation, or even interpenetration, but of a union; the incarnate Word is one, and there could be no duplication of the personality of the one redeemer God and man." (COPNET- Fr Matthias Wahba)

Politics - Emperor Marcian was supporting the Tome of Leo upon which the definition of Chalcedon is based, while the Egyptians were against the emperor. (Those who were in favour of Chalcedon were called "kings men" or "Melkites", not "pope's men", even though they were supporting Pope Leo's Tome.) Pope Leo was also very active in support of the primacy of the Holy See.

2. Their hostility to the antiochene position made them refuse to acknowledge the formula "Two distinct natures", specially as Nestorius agreed with the formula.

3. Loyalty to the "mia physis" formula they had received from St Athanasius.

Why did the Assyrian Church of the East reject Chalcedon?

It was impossible to translate the Chalcedonian formula from Greek into Syriac. Metropolitan Hilarion puts it this way:

The Greek word hypostasis in this context meant a specific person, Jesus Christ, God the Word, whereas the word physis (nature) referred to the humanity and divinity of Christ. When translated into Syriac, however, this terminological distinction could not be expressed accurately since in Syriac the word gnoma (used to translate hypostasis) carried the meaning of the individual expression of kyana (nature); thus Syriac writers normally spoke of natures and their gnoma. Consequentially whereas Severus of Antioch thought that one hypostasis implied one nature, diophysite writers claimed that two natures imply two hypostases.

In Syriac the Chalcedonian formula did not make sense!

An Assyrian metropolitan speaks

in an Australian Coptic parish

The Schism from a Coptic perspective

COMMON CHRISTOLOGICAL DECLARATION

BETWEEN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

AND THE ASSYRIAN CHURCH OF THE EAST

His Holiness John Paul II, Bishop of Rome and Pope of the Catholic Church, and His Holiness Mar Dinkha IV, Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, give thanks to God who has prompted them to this new brotherly meeting.

Both of them consider this meeting as a basic step on the way towards the full communion to be restored between their Churches. They can indeed, from now on, proclaim together before the world their common faith in the mystery of the Incarnation.

***

As heirs and guardians of the faith received from the Apostles as formulated by our common Fathers in the Nicene Creed, we confess one Lord Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, begotten of the Father from all eternity who, in the fullness of time, came down from heaven and became man for our salvation. The Word of God, second Person of the Holy Trinity, became incarnate by the power of the Holy Spirit in assuming from the holy Virgin Mary a body animated by a rational soul, with which he was indissolubly united from the moment of his conception.

Therefore our Lord Jesus Christ is true God and true man, perfect in his divinity and perfect in his humanity, consubstantial with the Father and consubstantial with us in all things but sin. His divinity and his humanity are united in one person, without confusion or change, without division or separation. In him has been preserved the difference of the natures of divinity and humanity, with all their properties, faculties and operations. But far from constituting "one and another", the divinity and humanity are united in the person of the same and unique Son of God and Lord Jesus Christ, who is the object of a single adoration.

Christ therefore is not an " ordinary man" whom God adopted in order to reside in him and inspire him, as in the righteous ones and the prophets. But the same God the Word, begotten of his Father before all worlds without beginning according to his divinity, was born of a mother without a father in the last times according to his humanity. The humanity to which the Blessed Virgin Mary gave birth always was that of the Son of God himself. That is the reason why the Assyrian Church of the East is praying the Virgin Mary as "the Mother of Christ our God and Saviour". In the light of this same faith the Catholic tradition addresses the Virgin Mary as "the Mother of God" and also as "the Mother of Christ". We both recognize the legitimacy and rightness of these expressions of the same faith and we both respect the preference of each Church in her liturgical life and piety.

This is the unique faith that we profess in the mystery of Christ. The controversies of the past led to anathemas, bearing on persons and on formulas. The Lord's Spirit permits us to understand better today that the divisions brought about in this way were due in large part to misunderstandings.

Whatever our Christological divergences have been, we experience ourselves united today in the confession of the same faith in the Son of God who became man so that we might become children of God by his grace. We wish from now on to witness together to this faith in the One who is the Way, the Truth and the Life, proclaiming it in appropriate ways to our contemporaries, so that the world may believe in the Gospel of salvation.

***

The mystery of the Incarnation which we profess in common is not an abstract and isolated truth. It refers to the Son of God sent to save us. The economy of salvation, which has its origin in the mystery of communion of the Holy Trinity — Father, Son and Holy Spirit —, is brought to its fulfilment through the sharing in this communion, by grace, within the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church, which is the People of God, the Body of Christ and the Temple of the Spirit.

Believers become members of this Body through the sacrament of Baptism, through which, by water and the working of the Holy Spirit, they are born again as new creatures. They are confirmed by the seal of the Holy Spirit who bestows the sacrament of Anointing. Their communion with God and among themselves is brought to full realization by the celebration of the unique offering of Christ in the sacrament of the Eucharist. This communion is restored for the sinful members of the Church when they are reconciled with God and with one another through the sacrament of Forgiveness. The sacrament of Ordination to the ministerial priesthood in the apostolic succession assures the authenticity of the faith, the sacraments and the communion in each local Church.

Living by this faith and these sacraments, it follows as a consequence that the particular Catholic churches and the particular Assyrian churches can recognize each other as sister Churches. To be full and entire, communion presupposes the unanimity concerning the content of the faith, the sacraments and the constitution of the Church. Since this unanimity for which we aim has not yet been attained, we cannot unfortunately celebrate together the Eucharist which is the sign of the ecclesial communion already fully restored.

Nevertheless, the deep spiritual communion in the faith and the mutual trust already existing between our Churches, entitle us from now on to consider witnessing together to the Gospel message and cooperating in particular pastoral situations, including especially the areas of catechesis and the formation of future priests.

In thanking God for having made us rediscover what already unites us in the faith and the sacraments, we pledge ourselves to do everything possible to dispel the obstacles of the past which still prevent the attainment of full communion between our Churches, so that we can better respond to the Lord's call for the unity of his own, a unity which has of course to be expressed visibly. To overcome these obstacles, we now establish a Mixed Committee for theological dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East.

Given at Saint Peter's, on 11 November 1994

K. MARDINKHA

IOANNES PAULUS PP. II

COMMON DECLARATION

OF POPE PAUL VI AND OF

THE POPE OF ALEXANDRIA SHENOUDA III

Tower of St. John in the Vatican gardens

Paul VI, bishop of Rome and Pope of the Catholic Church, and Shenouda III, Pope of Alexandria and patriarch of the See of St. Mark, give thanks in the Holy Spirit to God that, after the great event of the return of relics of St. Mark to Egypt, relations have further developed between the Churches of Rome and Alexandria so that they have now been able to meet personally together. At the end of their meetings and conversations they wish to state together the following:

We have met in the desire to deepen the relations between our Churches and to find concrete ways to overcome the obstacles in the way of our real cooperation in the service of our Lord Jesus Christ who has given us the ministry of reconciliation, to reconcile the world to Himself (2 Cor 5:18-20).

In accordance with our apostolic traditions transmitted to our Churches and preserved therein, and in conformity with the early three ecumenical councils, we confess one faith in the One Triune God, the divinity of the Only Begotten Son of God, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, the Word of God, the effulgence of His glory and the express image of His substance, who for us was incarnate, assuming for Himself a real body with a rational soul, and who shared with us our humanity but without sin. We confess that our Lord and God and Saviour and King of us all, Jesus Christ, is perfect God with respect to His Divinity, perfect man with respect to His humanity. In Him His divinity is united with His humanity in a real, perfect union without mingling, without commixtion, without confusion, without alteration, without division, without separation. His divinity did not separate from His humanity for an instant, not for the twinkling of an eye. He who is God eternal and invisible became visible in the flesh, and took upon Himself the form of a servant. In Him are preserved all the properties of the divinity and all the properties of the humanity, together in a real, perfect, indivisible and inseparable union.

The divine life is given to us and is nourished in us through the seven sacraments of Christ in His Church: Baptism, Chrism (Confirmation), Holy Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Matrimony and Holy Orders.

We venerate the Virgin Mary, Mother of the True Light, and we confess that she is ever Virgin, the God- bearer. She intercedes for us, and, as the Theotokos, excels in her dignity all angelic hosts.

We have, to a large degree, the same understanding of the Church, founded upon the Apostles, and of the important role of ecumenical and local councils. Our spirituality is well and profoundly expressed in our rituals and in the Liturgy of the Mass which comprises the centre of our public prayer and the culmination of our in corporation into Christ in His Church. We keep the fasts and feasts of our faith. We venerate the relics of the saints and ask the intercession of the angels and of the saints, the living and the departed. These compose a cloud of witnesses in the Church. They and we look in hope for the Second Coming of our Lord when His glory will be revealed to judge the living and the dead.

We humbly recognize that our Churches are not able to give more perfect witness to this new life in Christ because of existing divisions which have behind them centuries of difficult history. In fact, since the year 451 A.D., theological differences, nourished and widened by non-theological factors, have sprung up. These differences cannot be ignored. In spite of them, however, weare rediscovering ourselves as Churches witha common inheritance and are reaching out with determination and confidence in the Lord to achieve the fullness and perfection of that unity which is His gift.

As an aid to accomplishing this task, we are setting up a joint commission representing our Churches, whose function will be to guide common study in the fields of Church tradition, patristics, liturgy, theology, history and practical problems, so that by cooperation in common we may seek to resolve, in a spirit of mutual respect, the differences existing between our Churches and be able to proclaim together the Gospel in ways which correspond to the authentic message of the Lord and to the needs and hopes of todayss world. Atthe same time we express our gratitude and encouragement to other groups of Catholic and Orthodox scholars and pastors who devote their efforts to common activity in these and related fields.

With sincerity and urgency we recall that true charity, rooted in total fidelity to the one Lord Jesus Christ and in mutual respect for each oness traditions, is an essential element of this search for perfect communion.

In the name of this charity, we reject all forms of proselytism, in the sense of acts by which persons seek to disturb each other's communities by recruiting new members from each other through methods, or because of attitudes of mind, which are opposed to the exigencies of Christian love or to what should characterize the relationships between Churches. Let it cease, where it may exist. Catholics and Orthodox should strive to deepen charity and cultivate mutual consultation, reflection and cooperation in the social and intellectual fields and should humble themselves before God, supplicating Him who, as He has begun this work in us, will bring it to fruition.

As we rejoice in the Lord who has granted us the blessings of this meeting, our thoughts reach out to the thousands of suffering and homeless Palestinian people. We deplore any misuse of religious arguments for political purposes in this area. We earnestly desire and look for a just solution for the Middle East crisis so that true peace with justice should prevail, especially in that land which was hallowed by the preaching, death and resurrection of our Lord and Saviour Jusus Christ, and by the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, whom we venerate together as the Theotokos. May God, the giver of all good gifts, hear our prayers and bless our endeavours.

From the Vatican, May 10, 1973.

WHAT ALL THIS CAN TEACH US.

Two churches of apostolic origin, each with its own tradition that springs from the synergy between the Holy Spirit and their ecclesial life as eucharistic community down the ages and shaped by its culture and its historical circumstances. The Assyrian Church of the East has a semitic culture and is isolated from the church of the Roman Empire because it has grown up in the Persian Empire and did not get invited to ecumenical councils. Alexandria is an intellectual hub of Eastern Christianity, supplier of grain to the Empire, yet wanting independence from the Greeks. The two traditions clash, each considering the other to be heretical. They are both regional versions of the Christian faith that cannot recognise one another. The language of both sides are, perhaps, inadequate, the Antiochene expression of the Incarnation leading some to suppose that the unity of the two natures is in our own minds rather than in the Incarnation itself, while the Alexandrine tradition led some to believe that, for them, divinity and humanity are somehow mixed into a single divine-human nature. Yet both traditions are the fruit of a single eucharistic life, both churches daily invoked the same Holy Spirit, and, many centuries later, both churches could sign a common declaration of faith with the Holy See on a subject that had previously bitterly divided them from each other and from Catholic communion.

I believe this has much to teach us about the other divisions in Christendom and may indicate the way to resolve them.

THE FOUNT OF UNITY AMONG CHRISTIANS

1 John 4, 7...

7 Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God. 8 Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love. 9 In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. 10 In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins. 11 Beloved, if God so loved us, we also ought to love one another. 12 No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God abides in us and his love is perfected in us.

13 By this we know that we abide in him and he in us, because he has given us of his Spirit. 14 And we have seen and testify that the Father has sent his Son to be the Savior of the world. 15 Whoever confesses that Jesus is the Son of God, God abides in him, and he in God. 16 So we have come to know and to believe the love that God has for us. God is love, and whoever abides in love abides in God, and God abides in him.

My flesh is real food and my blood is real drink.He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood lives in me and I in him. As I, who am sent from the living Father and draw life from the Father, so whoever eats me will draw life from me.

John 17, 21 - 23

May they all be one. Father, may they be one in us as you are in me and I am in you, that the world may believe it was you who sent me. I have given them the glory you gave to me, thatnthey may be one as we are one. With me in them and you in me, may they be so completely one that the world will realise that it was you who sent me and that I have loved them as much as you loved me.

Christ is the source of the Church and we are Christians because Christ lives in us and we in him. This is the basic Christianity, not our version of it but Christ's.

Where the Eucharist is, there is the Church because it is in the Eucharist that we receive his body and blood in such a way that we are in him and he in us: we are the body of Christ. The Catechism says:

1324 The Eucharist is "the source and summit of the Christian life."136 "The other sacraments, and indeed all ecclesiastical ministries and works of the apostolate, are bound up with the Eucharist and are oriented toward it. For in the blessed Eucharist is contained the whole spiritual good of the Church, namely Christ himself, our Pasch.Now there is only one Eucharist, wherever by whoever it is celebrated, in Rome, Peru, London, Baghdad, Moscow, Alexandria or Mosul; and in every single Mass is "contained the whole spiritual good of the Church, namely Christ himself, our Pasch." Where the Eucharist is, there is the Church.

There is only one Mass in which Christ is priest, victim and altar. As St John Chrysostom said, just God said, "Let there be light," and this command from eternity resonates for ever throughout creation, so Jesus said, "This is my body...This is the chalice of my blood," and this becomes true at every Mass. There is only one Eucharist, so that the priest celebrates in persona Christi because Christ is the celebrant at all masses as we approach the heavenly tabernacle, and all who participate in one Mass also participate spiritually at every other Mass, across time and space, and even across the things that divide us. Ignorant Orthodox monks may call the pope "anti-Christ", but they share the body and blood of Christ with him every time they take part in the Divine Liturgy. The whole of God's Church is visibly present through every local congregation.

The liturgy is always the work of the local church, and it the source of all the Church's powers, as Sacrosanctum Concilium tells us:

This means that the sources of Tradition are the multiple traditions of local churches through the activity of the Holy Spirit.

ch 1, 10. Nevertheless the liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the font from which all her power flows. For the aim and object of apostolic works is that all who are made sons of God by faith and baptism should come together to praise God in the midst of His Church, to take part in the sacrifice, and to eat the Lord's supper.

Some opponents of this understanding of the Church accuse us of adopting the Anglican branch theory, but this is not true either historically nor theologically.

Historically, the origin is Russian Orthodox. Metropolitan John Zizioulas says that the importance of the local church given in Vatican II

Mainly to the so-called “eucharistic ecclesiology” of the Russian theologian Nicolai Afanassieff, who formulated the axiom “wherever the Eucharist is, there is the Church”. This meant that each local Church in which the Eucharist is celebrated should be regarded as the full and Catholic Church. The Roman Catholic theologians were influenced by this approach and, as a result, a theology of the local Church entered the documents of the Council.Theologically, the Branch Theory was an effort to give legitimacy to the Anglican Church as a separate entity. Eucharistic ecclesiology takes legitimacy away from all divisions, seeing them as evidence of our shortcomings, of our worldliness. The unity of the Church, whether we are speaking of the local church, the regional church or the universal church, or of any kind of Christian community living, has been given by St John:

With me in them and you in me, may they be so completely one that the world will realise that it was you who sent me and that I have loved them as much as you loved me.We are to be so united that the world is surprised by it: it is to be what attracts the world to the Gospel. Divisions are what hide Christ from the world and keep the world in ignorance of Christ. Even any kind of universal unity that mirrors that of the world itself is not sufficient.

Does that mean that we should forget all that divides us, and just come together. Unfortunately, it isn't that simple. Being united to one another implies, not only being one with our neighbour, but also across time. We owe our very existence as churches to the passing, from one generation to the next, of the apostolic tradition in the form it has come down to us. Becoming one with our neighbour in the present involves reconciling our traditions one with the other, as we have seen taking place between our Assyrian and Coptic brethren. In that way, the Catholic life of the whole Church will be deepened and enriched. To ignore the past in favour of a modern but rootless unity may be legitimate for some Protestant communities, but it would be a denial of our very being as Apostolic churches.

APPLYING WHAT WE HAVE LEARNED SO FAR TO THE CHURCH IN OUR DAY

Vatican I was similar to the Council of Ephesus in that it was intolerant of any opposition, and anyone whose view was different from the dominant one was shouted down.

Ephesus gave us Catholic teaching we have benefited from, and we call Mary Mother of God till this day; but it was unaware that the alexandrian tradition was not enough and that the Church needed the Antiochene tradition too. Thus, Ephesus cried out for Chalcedon. It was not Chalcedon's fault that its doctrine could not be translated into Syriac! What did Vatican I cry out for?

Vatican I was unaware of the fact that the Eastern Orthodox tradition is also Catholic Tradition, that it has the same origin in the apostolic preaching, the same stream of living water brought about by the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the local eucharistic communities, and the same fruit in generations of saintly living. Objections to Catholic teaching that come from the Orthodox tradition are not the same as those made by people who live outside the Tradition. As the Catholic Church as body of Christ is whole in all its parts, and while we accept that Vatican I, as supreme expression of western Catholic tradition, was assisted by the Holy Spirit, the dogmas made no sense to Orthodox tradition. There is a need to dig into both traditions to see where they meet. This is what happening in the Catholic-Orthodox dialogue; and this dialogue is making real changes in how we understand the papacy. We are going back to the sources and are asking ourselves what St Ignatius of Antioch meant when he said that "the Roman Church presides in love." We are moving away from the Catholic Church as a "perfect society" and the pope with universal jurisdiction claimed and accepted by the Church to "Church as communion" and the pope as universal minister of love. As Pope Francis says,

“Real power is service. As He did, He who came not to be served but to serve, and His service was the service of the Cross. He humbled Himself unto death, even death on a cross for us, to serve us, to save us. And there is no other way in the Church to move forward. For the Christian, getting ahead, progress, means humbling oneself. If we do not learn this Christian rule, we will never, ever be able to understand Jesus’ true message on power.”

In a diocese, he said, the bishop is the "vicar of that Jesus who, at the Last Supper, knelt to wash the feet of the apostles," and the pope is called to truly be "the servant of the servants of God."

Both in our pastoral work and in our ecumenism, we must always remember that we must act in such a way that Jesus can use us as instruments of his presence. His is the only presence that saves, but he can save through us or through anyone who is willing. He is the Good Shepherd who leaves the 99 sheep in the sheepfold in search for the one. He never allows the walls of the sheepfold to keep him away from a lost sheep, even if he built the walls himself. They were never built to keep sheep out: only to protect those who are in. Christ is the human face of God's merciful love which gathers people into communion with himself. We must be ready to break our routine, look anywhere and everywhere for opportunities to serve, so that in our service they may encounter Christ. Also, we must be alert to meet him in strange and unexpected ways ourselves and be open to what he wants to tell us."We must never forget: for the disciples of Jesus -- yesterday, today and forever -- the only authority is the authority of service; the only power is the power of the cross," he said.

We are already one with all who have encountered Jesus, all who dwell in him and he in them. Even if they are Protestants and know nothing of the Mass, they are connected with the Mass by their faith in Christ, and we are present in the Mass for them as well as for ourselves. Let our apostolate be an outreach of love that reflects the love of God for all.

Pope Francis again:

Speaking about the encounter brings to mind “The calling of St Matthew”, the Caravaggio in the Church of St Louis of the French, which I used to spend much time in front of every time I came to Rome. None of them who were there, including Matthew, greedy for money, could believe the message in that finger pointing at him, the message in those eyes that looked at him with mercy and chose him for the sequela. He felt this astonishment of the encounter. The encounter with Christ who comes and invites us is like this.

Everything in our life, today as in the time of Jesus, begins with an encounter. An encounter with this Man, the carpenter from Nazareth, a man like all men and at the same time different. Let us consider the Gospel of John, there where it tells of the disciples’ first encounter with Jesus (cf. 1:35-42). Andrew, John, Simon: they feel themselves being looked at to their very core, intimately known, and this generates surprise in them, an astonishment which immediately makes them feel bonded to Him.... Or when, after the Resurrection, Jesus asks Peter: “Do you love me?” (Jn 21:15), and Peter responds: “Yes”; this yes was not the result of a power of will, it did not come only by decision of the man Simon: it came even before from Grace, it was that “primarear”, that preceding of Grace. This was the decisive discovery for St Paul, for St Augustine, and so many other saints: Jesus Christ is always first, He primareas us, awaits us, Jesus Christ always precedes us; and when we arrive, He has already been waiting. He is like the almond blossom: the one that blooms first, and announces the arrival of spring.

Dr Peter Kreeft on being

both Catholic and Protestant

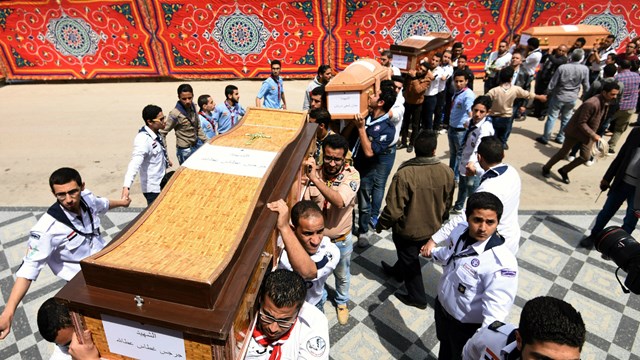

“Today we are witnessing the persecution of Christians and… I was just in Albania… They told me that they didn’t ask if you were Catholic or Orthodox… Are you Christian? Boom! Currently in the Middle East, in Africa, in many places, how many Christians have died! They don’t ask them if they are Pentecostal, Lutheran, Calvinist, Anglican, Catholic, Orthodox… Are they Christians? They kill them because they believe in Christ. This is the ecumenism of blood.

.jpg)