Foreword

Martin Luther’s struggle with God drove and defined his whole life. The question, How can I find a gracious God? plagued him constantly. He found the gracious God in the gospel of Jesus Christ. “True theology and the knowledge of God are in the crucified Christ.”

In 2017, Catholic and Lutheran Christians will most fittingly look back on events that occurred 500 years earlier by putting the gospel of Jesus Christ at the center. The gospel should be celebrated and communicated to the people of our time so that the world may believe that God gives Godself to human beings and calls us into communion with Godself and God’s church. Herein lies the basis for our joy in our common faith.

To this joy also belongs a discerning, self-critical look at ourselves, not only in our history, but also today. We Christians have certainly not always been faithful to the gospel; all too often we have conformed ourselves to the thought and behavioral patterns of the surrounding world. Repeatedly, we have stood in the way of the good news of the mercy of God.

Both as individuals and as a community of believers, we all constantly require repentance and reform—encouraged and led by the Holy Spirit. “When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said ‘Repent,’ He called for the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.” Thus reads the opening statement of Luther’s 95 Theses from 1517, which triggered the Reformation movement.

Although this thesis is anything but self-evident today, we Lutheran and Catholic Christians want to take it seriously by directing our critical glance first at ourselves and not at each other. We take as our guiding rule the doctrine of justification, which expresses the message of the gospel and therefore “constantly serves to orient all the teaching and practice of our churches to Christ” (Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification).

The true unity of the church can only exist as unity in the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ. The fact that the struggle for this truth in the sixteenth century led to the loss of unity in Western Christendom belongs to the dark pages of church history. In 2017, we must confess openly that we have been guilty before Christ of damaging the unity of the church. This commemorative year presents us with two challenges: the purification and healing of memories, and the restoration of Christian unity in accordance with the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ (Eph 4:4–6).

The following text describes a way “from conflict to communion”—a way whose goal we have not yet reached. Nevertheless, the Lutheran–Catholic Commission for Unity has taken seriously the words of Pope John XXIII, “The things that unite us are greater than those that divide us.”

We invite all Christians to study the report of our Commission both open-mindedly and critically, and to come with us along the way to a deeper communion of all Christians.

Karlheinz DiezEero Huovinen

Auxiliary Bishop of Fulda

(on behalf of the Catholic co-chair)Bishop Emeritus of Helsinki

Lutheran co-chair

Introduction

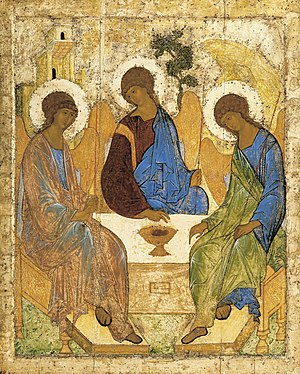

1. In 2017, Lutheran and Catholic Christians will commemorate together the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation. Lutherans and Catholics today enjoysciples, but immediately gave them the Spirit and charged them to preach the Gospel and to forgive sins, so the Pope and the Lutherans come together in thanksgiving and forgiveness and embark on the way to unity and a growth in mutual understanding, cooperation, and respect. They have come to acknowledge that more unites than divides them: above all, common faith in the Triune God and the revelation in Jesus Christ, as well as recognition of the basic truths of the doctrine of justification.

2. Already the 450th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession in 1980 offered both Lutherans and Catholics the opportunity to develop a common understanding of the foundational truths of the faith by pointing to Jesus Christ as the living center of our Christian faith.(1) On the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s birth in 1983, the international dialogue between Roman Catholics and Lutherans jointly affirmed a number of Luther’s essential concerns. The commission’s report designated him “Witness to Jesus Christ” and declared, “Christians, whether Protestant or Catholic, cannot disregard the person and the message of this man.”(2)

3. The upcoming year of 2017 challenges Catholics and Lutherans to discuss in dialogue the issues and consequences of the Wittenberg Reformation, which centered on the person and thought of Martin Luther, and to develop perspectives for the remembrance and appropriation of the Reformation today. Luther’s reforming agenda poses a spiritual and theological challenge for both contemporary Catholics and Lutherans.

Chapter I

Commemorating the Reformation in an

Ecumenical and Global Age

4. Every commemoration has its own context. Today, the context includes three main challenges, which present both opportunities and obligations: (1) It is the first commemoration to take place during the ecumenical age. Therefore, the common commemoration is an occasion to deepen communion between Catholics and Lutherans. (2) It is the first commemoration in the age of globalization. Therefore, the common commemoration must incorporate the experiences and perspectives of Christians from South and North, East and West. (3) It is the first commemoration that must deal with the necessity of a new evangelization in a time marked by both the proliferation of new religious movements and, at the same time, the growth of secularization in many places. Therefore, the common commemoration has the opportunity and obligation to be a common witness of faith.

The character of previous commemorations

5. Relatively early, 31 October 1517 became a symbol of the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation. Still today, many Lutheran churches remember each year on 31 October the event known as “the Reformation.” The centennial celebrations of the Reformation have been lavish and festive. The opposing viewpoints of the different confessional groups have been especially visible at these events. For Lutherans, these commemorative days and centennials were occasions for telling once again the story of the beginning of the characteristic— “evangelical”—form of their church in order to justify their distinctive existence. This was naturally tied to a critique of the Roman Catholic Church. On the other side, Catholics took such commemorative events as opportunities to accuse Lutherans of an unjustifiable division from the true church and a rejection of the gospel of Christ.

6. Political and church-political agendas frequently shaped these earlier centenary commemorations. In 1617, for example, the observance of the 100th anniversary helped to stabilize and revitalize the common Reformation identity of Lutherans and Reformed at their joint commemorative celebrations. Lutherans and Reformed demonstrated their solidarity through strong polemics against the Roman Catholic Church. Together they celebrated Luther as the liberator from the Roman yoke. Much later, in 1917, amidst the First World War, Luther was portrayed as a German national hero.

The First Ecumenical Commemoration

7. The year 2017 will see the first centennial commemoration of the Reformation to take place during the ecumenical age. It will also mark fifty years of Lutheran–Roman Catholic dialogue. As part of the ecumenical movement, praying together, worshipping together, and serving their communities together have enriched Catholics and Lutherans. They also face political, social, and economic challenges together. The spirituality evident in interconfessional marriages has brought forth new insights and questions. Lutherans and Catholics have been able to reinterpret their theological traditions and practices, recognizing the influences they have had on each other. Therefore, they long to commemorate 2017 together.

8. These changes demand a new approach. It is no longer adequate simply to repeat earlier accounts of the Reformation period, which presented Lutheran and Catholic perspectives separately and often in opposition to one another. Historical remembrance always selects from among a great abundance of historical moments and assimilates the selected elements into a meaningful whole. Because these accounts of the past were mostly oppositional, they not infrequently intensified the conflict between the confessions and sometimes led to open hostility.

9. The historical remembrance has had material consequences for the relationship of the confessions to each other. For this reason, a common ecumenical remembrance of the Lutheran Reformation is both so important and at the same time so difficult. Even today, many Catholics associate the word “Reformation” first of all with the division of the church, while many Lutheran Christians associate the word “Reformation” chiefly with the rediscovery of the gospel, certainty of faith and freedom. It will be necessary to take both points of departure seriously in order to relate the two perspectives to each other and bring them into dialogue.

Commemoration in a new global and secular context

10. In the last century, Christianity has become increasingly global. There are today Christians of various confessions throughout the whole world; the number of Christians in the South is growing, while the number of Christians in the North is shrinking. The churches of the South are continually assuming a greater importance within worldwide Christianity. These churches do not easily see the confessional conflicts of the sixteenth century as their own conflicts, even if they are connected to the churches of Europe and North America through various Christian world communions and share with them a common doctrinal basis. With regard to the year 2017, it will be very important to take seriously the contributions, questions, and perspectives of these churches.

11. In lands where Christianity has already been at home for many centuries, many people have left the churches in recent times or have forgotten their ecclesial traditions. In these traditions, churches have handed on from generation to generation what they had received from their encounter with the Holy Scripture: an understanding of God, humanity, and the world in response to the revelation of God in Jesus Christ; the wisdom developed over the course of generations from the experience of lifelong engagement of Christians with God; and the treasury of liturgical forms, hymns and prayers, catechetical practices, and diaconal services. As a result of this forgetting, much of what divided the church in the past is virtually unknown today.

12. Ecumenism, however, cannot base itself on forgetfulness of tradition. But how, then, will the history of the Reformation be remembered in 2017? What of that which the two confessions fought over in the sixteenth century deserves to be preserved? Our fathers and mothers in the faith were convinced that there was something worth fighting for, something that was necessary for a life with God. How can the often forgotten traditions be handed on to our contemporaries so as not to remain objects of antiquarian interest only, but rather support a vibrant Christian existence? How can the traditions be passed on in such a way that they do not dig new trenches between Christians of different confessions?

New challenges for the 2017 commemoration

13. Over the centuries, church and culture often have been interwoven in the most intimate way possible. Much that has belonged to the life of the church has, over the course of centuries, also found a place in the cultures of those countries and plays a role in them even to this day, even at times independently of the churches. The preparations for 2017 will need to identify these various elements of the tradition now present in the culture, to interpret them, and to lead a conversation between church and culture in light of these different aspects.

14. For more than a hundred years, Pentecostal and other charismatic movements have become very widespread across the globe. These powerful movements have put forward new emphases that have made many of the old confessional controversies seem obsolete. The Pentecostal movement is present in many other churches in the form of the charismatic movement, creating new commonalities and communities across confessional boundaries. Thus, this movement opens up new ecumenical opportunities while, at the same time, creating additional challenges that will play a significant role in the observance of the Reformation in 2017.

15. While the previous Reformation anniversaries took place in confessionally homogenous lands, or lands at least where a majority of the population was Christian, today Christians live worldwide in multireligious environments. This pluralism poses a new challenge for ecumenism, making ecumenism not superfluous but, on the contrary, all the more urgent, since the animosity of confessional oppositions harms Christian credibility. How Christians deal with differences among themselves can reveal something about their faith to people of other religions. Because the question of how to handle inner-Christian conflict is especially acute on the occasion of remembering the beginning of the Reformation, this aspect of the changed situation deserves special attention in our reflections on the year 2017.

Chapter II

New Perspectives on Martin Luther and the Reformation

16. What happened in the past cannot be changed, but what is remembered of the past and how it is remembered can, with the passage of time, indeed change. Remembrance makes the past present. While the past itself is unalterable, the presence of the past in the present is alterable. In view of 2017, the point is not to tell a different history, but to tell that history differently.

17. Lutherans and Catholics have many reasons to retell their history in new ways. They have been brought closer together through family relations, through their service to the larger world mission, and through their common resistance to tyrannies in many places. These deepened contacts have changed mutual perceptions, bringing new urgency for ecumenical dialogue and further research. The ecumenical movement has altered the orientation of the churches’ perceptions of the Reformation: ecumenical theologians have decided not to pursue their confessional self-assertions at the expense of their dialogue partners but rather to search for that which is common within the differences, even within the oppositions, and thus work toward overcoming church-dividing differences.

Contributions of research on the Middle Ages

18. Research has contributed much to changing the perception of the past in a number of ways. In the case of the Reformation, these include the Protestant as well as the Catholic accounts of church history, which have been able to correct previous confessional depictions of history through strict methodological guidelines and reflection on the conditions of their own points of view and presuppositions. On the Catholic side that applies especially to the newer research on Luther and Reformation and, on the Protestant side, to an altered picture of medieval theology and to a broader and more differentiated treatment of the late Middle Ages. In current depictions of the Reformation period, there is also new attention to a vast number of non-theological factors—political, economic, social, and cultural. The paradigm of “confessionalization” has made important corrections to previous historiography of the period.

19. The late Middle Ages are no longer seen as total darkness, as often portrayed by Protestants, nor are they perceived as entirely light, as in older Catholic depictions. This age appears today as a time of great oppositions—of external piety and deep interiority; of works-oriented theology in the sense of do ut des (“I give you so that you give me”) and conviction of one’s total dependence on the grace of God; of indifference toward religious obligations, even the obligations of office, and serious reforms, as in some of the monastic orders.

20. The church was anything but a monolithic entity; the corpus christianum encompassed very diverse theologies, lifestyles, and conceptions of the church. Historians say that the fifteenth century was an especially pious time in the church. During this period, more and more lay people received a good education and so were eager to hear better preaching and a theology that would help them to lead Christian lives. Luther picked up on such streams of theology and piety and developed them further.

Twentieth-century Catholic research on Luther

21. Twentieth-century Catholic research on Luther built upon a Catholic interest in Reformation history that awakened in the second half of the nineteenth century. These theologians followed the efforts of the Catholic population in the Protestant-dominated German empire to free themselves from a one-sided, anti-Roman, Protestant historiography. The breakthrough for Catholic scholarship came with the thesis that Luther overcame within himself a Catholicism that was not fully Catholic. According to this view, the life and teaching of the church in the late Middle Ages served mainly as a negative foil for the Reformation; the crisis in Catholicism made Luther’s religious protest quite convincing to some.

22. In a new way, Luther was portrayed as an earnest religious person and conscientious man of prayer. Painstaking and detailed historical research has demonstrated that Catholic literature on Luther over the previous four centuries right up through modernity had been significantly shaped by the commentaries of Johannes Cochaleus, a contemporary opponent of Luther and advisor to Duke George of Saxony. Cochaleus had characterized Luther as an apostatized monk, a destroyer of Christendom, a corrupter of morals, and a heretic. The achievement of this first period of critical, but sympathetic, engagement with Luther’s character was the freeing of Catholic research from the one-sided approach of such polemical works on Luther. Sober historical analyses by other Catholic theologians showed that it was not the core concerns of the Reformation, such as the doctrine of justification, which led to the division of the church but, rather, Luther’s criticisms of the condition of the church at his time that sprang from these concerns.

23. The next step for Catholic research on Luther was to uncover analogous contents embedded in different theological thought structures and systems, carried out especially by a systematic comparison between the exemplary theologians of the two confessions, Thomas Aquinas and Martin Luther. This work allowed theologians to understand Luther’s theology within its own framework. At the same time, Catholic research examined the meaning of the doctrine of justification within the Augsburg Confession. Here Luther’s reforming concerns could be set within the broader context of the composition of the Lutheran confessions, with the result that the intention of the Augsburg Confession could be seen as expressing fundamental reforming concerns as well as preserving the unity of the church.

Ecumenical projects preparing the way for consensus

24. These efforts led directly to the ecumenical project, begun in 1980 by Lutheran and Catholic theologians in Germany on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession, of a Catholic recognition of the Augsburg Confession. The extensive achievements of a later ecumenical working group of Protestant and Catholic theologians, tracing its roots back to this project of Catholic research on Luther, resulted in the study The Condemnations of the Reformation Era: Do They Still Divide?(3)

25. The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification,(4) signed by both the Lutheran World Federation and the Roman Catholic Church in 1999, built on this groundwork as well as on the work of the US dialogue Justification by Faith,(5) and affirmed a consensus in the basic truths of the doctrine of justification between Lutherans and Catholics.

Catholic developments

26. The Second Vatican Council, responding to the scriptural, liturgical, and patristic revival of the preceding decades, dealt with such themes as esteem and reverence for the Holy Scripture in the life of the church, the rediscovery of the common priesthood of all the baptized, the need for continual purification and reform of the church, the understanding of church office as service, and the importance of the freedom and responsibility of human beings, including the recognition of religious freedom.

27. The Council also affirmed elements of sanctification and truth even outside the structures of the Roman Catholic Church. It asserted, “some and even very many of the significant elements and endowments which together go to build up and give life to the Church itself, can exist outside the visible boundaries of the Catholic Church,” and it named these elements “the written word of God; the life of grace; faith, hope and charity, with the other interior gifts of the Holy Spirit, and visible elements too” (UR 1).(6) The Council also spoke of the “many liturgical actions of the Christian religion” that are used by the divided “brethren” and said, “these most certainly can truly engender a life of grace in ways that vary according to the condition of each Church or Community. These liturgical actions must be regarded as capable of giving access to the community of salvation” (UR 3). The acknowledgement extended not only to the individual elements and actions in these communities, but also to the “divided churches and communities” themselves. “For the Spirit of Christ has not refrained from using them as means of salvation” (UR 1.3).

28. In light of the renewal of Catholic theology evident in the Second Vatican Council, Catholics today can appreciate Martin Luther’s reforming concerns and regard them with more openness than seemed possible earlier.

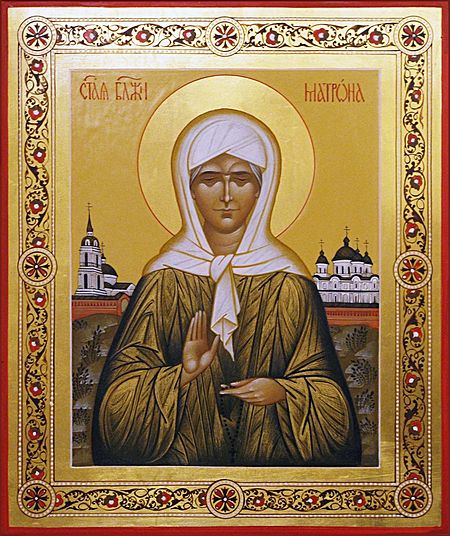

29. Implicit rapprochement with Luther’s concerns has led to a new evaluation of his catholicity, which took place in the context of recognizing that his intention was to reform, not to divide, the church. This is evident in the statements of Johannes Cardinal Willebrands and Pope John Paul II.(7) The rediscovery of these two central characteristics of his person and theology led to a new ecumenical understanding of Luther as a “witness to the gospel.”

30. Pope Benedict also recognized the ways in which the person and theology of Martin Luther pose a spiritual and theological challenge to Catholic theology today when, in 2011, he visited the Augustinian Friary in Erfurt where Luther had lived as a friar for about six years. Pope Benedict commented, “What constantly exercised [Luther] was the question of God, the deep passion and driving force of his whole life’s journey. ‘How do I find a gracious God?’ – this question struck him in the heart and lay at the foundation of all his theological searching and inner struggle. For him, theology was no mere academic pursuit, but the struggle for oneself, which in turn was a struggle for and with God. ‘How do I find a gracious God?’ The fact that this question was the driving force of his whole life never ceases to make an impression on me. For who is actually concerned about this today—even among Christians? What does the question of God mean in our lives? In our preaching? Most people today, even Christians, set out from the presupposition that God is not fundamentally interested in our sins and virtues.”(8)

Lutheran developments

31. Lutheran research on Luther and the Reformation also underwent considerable development. The experiences of two world wars broke down assumptions about the progress of history and the relationship between Christianity and Western culture, while the rise of kerygmatic theology opened a new avenue for thinking about Luther. Dialogue with historians helped to integrate historical and social factors into descriptions of Reformation movements. Lutheran theologians recognized the entanglements of theological insights and political interests not only on the part of Catholics, but also on their own side. Dialogue with Catholic theologians helped them to overcome one-sided confessional approaches and to become more self-critical about aspects of their own traditions.

The importance of ecumenical dialogues

32. The dialogue partners are committed to the doctrines of their respective churches, which, according to their own convictions, express the truth of the faith. The doctrines demonstrate great commonalities but may differ, or even be opposed, in their formulations. Because of the former, dialogue is possible; because of the latter, dialogue is necessary.

33. Dialogue demonstrates that the partners speak different languages and understand the meanings of words differently; they make different distinctions and think in different thought forms. However, what appears to be an opposition in expression is not always an opposition in substance. In order to determine the exact relationship between respective articles of doctrine, texts must be interpreted in the light of the historical context in which they arose. That allows one to see where a difference or opposition truly exists and where it does not.

34. Ecumenical dialogue means being converted from patterns of thought that arise from and emphasize the differences between the confessions. Instead, in dialogue the partners look first for what they have in common and only then weigh the significance of their differences. These differences, however, are not overlooked or treated casually, for ecumenical dialogue is the common search for the truth of the Christian faith.

Chapter III

A Historical Sketch of the Lutheran Reformation

and the Catholic Response

35. Today we are able to tell the story of the Lutheran Reformation together. Even though Lutherans and Catholics have different points of view, because of ecumenical dialogue they are able to overcome traditional anti-Protestant and anti-Catholic hermeneutics in order to find a common way of remembering past events. The following chapter is not a full description of the entire history and all the disputed theological points. It highlights only some of the most important historical situations and theological issues of the Reformation in the sixteenth century.

What does reformation mean?

36. In antiquity, the Latin noun reformatio referred to the idea of changing a bad present situation by returning to the good and better times of the past. In the Middle Ages, the concept of reformatio was very often used in the context of monastic reform. The monastic orders engaged in reformation in order to overcome the decline of discipline and religious lifestyle. One of the greatest reform movements originated in the tenth century in the Abbey of Cluny.

37. In the late Middle Ages, the concept of the necessity of reform was applied to the whole church. The church councils and nearly every diet of the Holy Roman Empire were concerned with reformatio. The Council of Constance (1414–1418) regarded the reform of the church “in head and members” as necessary.(9) A widely disseminated reform document entitled “Reformacion keyser Sigmunds” called for the restoration of right order in almost every area of life. At the end of the fifteenth century, the idea of reformation also spread to the government and university.(10)

38. Luther himself seldom used the concept of “reformation.” In his “Explanations of the Ninety-Five Theses,” Luther states, “The church needs a reformation which is not the work of man, namely the pope, or of many men, namely the cardinals, both of which the most recent council has demonstrated, but it is the work of the whole world, indeed it is the work of God alone. However, only God who has created time knows the time for this reformation.”(11) Sometimes Luther used the word “reformation” in order to describe improvements of order, for example of the universities. In his reform treatise “Address to the Christian Nobility” of 1520, he called for “a just, free council” that would allow the proposals for reform to be debated.(12)

39. The term “Reformation” came to be used as a designation for the complex of historical events that, in the narrower sense, encompass the years 1517 to 1555, thus from the time of the spread of Martin Luther’s “Ninety-five Theses” up until the Peace of Augsburg. The theological and ecclesiastical controversy that Luther’s theology had triggered quickly became entangled with politics, the economy, and culture, due to the situation at the time. What is designated by the term “Reformation” thus reaches far beyond what Luther himself taught and intended. The concept of “Reformation” as a designation of an entire epoch comes from Leopold von Ranke who, in the nineteenth century, popularized the custom of speaking of an “age of Reformation.”

Reformation flashpoint: controversy over indulgences

40. On October 31, 1517, Luther sent his “Ninety-five Theses,” titled, “Disputation on the Efficacy and Power of Indulgences,” as an appendix to a letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz. In this letter, Luther expressed serious concerns about preaching and the practice of indulgences occurring under the responsibility of the Archbishop and urged him to make changes. On the same day, he wrote another letter to his Diocesan Bishop Hieronymus of Brandenburg. When Luther sent his theses to a few colleagues and most likely posted them on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, he wished to inaugurate an academic disputation on open and unresolved questions regarding the theory and practice of indulgences.

41. Indulgences played an important role in the piety of the time. An indulgence was understood as a remission of temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt had already been forgiven. Christians could receive an indulgence under certain prescribed conditions—such as prayer, acts of charity, and almsgiving—through the action of the church, which was thought to dispense and apply the treasury of the satisfactions of Christ and the saints to penitents.

42. In Luther’s opinion, the practice of indulgences damaged Christian spirituality. He questioned whether indulgences could free the penitents from penalties imposed by God; whether any penalties imposed by priests would be transferred into purgatory; whether the medicinal and purifying purpose of penalties meant that a sincere penitent would prefer to suffer the penalties instead of being liberated from them; and whether the money given for indulgences should instead be given to the poor. He also wondered about the nature of the treasury of the church out of which the pope offered indulgences.

Luther on trial

43. Luther’s “Ninety-five Theses” spread very swiftly throughout Germany and caused a great sensation while also doing serious damage to the indulgence campaigns. Soon it was rumored that Luther would be accused of heresy. Already in December 1517, the Archbishop of Mainz had sent the “Ninety-five Theses” to Rome together with some additional material for an examination of Luther’s theology.

44. Luther was surprised by the reaction to his theses, as he had not planned a public event but rather an academic disputation. He feared that the theses would be easily misunderstood if read by a wider audience. Thus, in late March 1518, he published a vernacular sermon, “On Indulgence and Grace” (“Sermo von Ablass und Gnade”). It was an extraordinarily successful pamphlet that quickly made Luther a figure well known to the German public. Luther repeatedly insisted that, apart from the first four propositions, the theses were not his own definitive assertions but rather propositions written for disputation.

45. Rome was concerned that Luther’s teaching undermined the doctrine of the church and the authority of the pope. Thus, Luther was called to Rome in order to answer to the curial court for his theology. However, upon the request of the Electoral Prince of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, the trial was transferred to Germany, to the Imperial Diet at Augsburg, where Cardinal Cajetan was given the mandate to interrogate Luther. The papal mandate said that either Luther was to recant or, in the event that Luther refused, the Cardinal had the power to ban Luther immediately or to arrest him and bring him to Rome. After the meeting, Cajetan drafted a statement for the magisterium, and the pope promulgated it soon after the interrogation in Augsburg without any response to Luther’s arguments.(13)

46. A fundamental ambivalence persisted throughout the whole process leading up to Luther’s excommunication. Luther offered questions for disputation and put forward arguments. He and the public, informed through many pamphlets and publications about his position and the ongoing process, expected an exchange of arguments. Luther was promised a fair trial. Nevertheless, although he was assured that he would be heard, he repeatedly received the message that he either had to recant or be proclaimed a heretic.

47. On 13 October 1518, in a solemn protestatio, Luther claimed that he was in agreement with the Holy Roman Church and that he could not recant unless he were convinced that he was wrong. On 22 October, he again insisted that he thought and taught within the scope of the Roman Church’s teaching.

Failed encounters

48. Before his encounter with Luther, Cardinal Cajetan had studied the Wittenberg professor’s writings very carefully and had even written treatises on them. But Cajetan interpreted Luther within his own conceptual framework and thus misunderstood him on the assurance of faith, even while correctly representing the details of his position. For his part, Luther was not familiar with the cardinal’s theology, and the interrogation, which allowed only for limited discussion, pressured Luther to recant. It did not provide an opportunity for Luther to understand the cardinal’s position. It is a tragedy that two of the most outstanding theologians of the sixteenth century encountered one another in a trial of heresy.

49. In the following years, Luther’s theology developed rapidly, giving rise to new topics of controversy. The accused theologian worked to defend his position and to gain allies in the struggle with those who were about to declare him a heretic. Many publications both for and against Luther appeared, but there was only one disputation, in 1519, in Leipzig between Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt and Luther on the one side, and Johannes Eck, on the other.

The condemnation of Martin Luther

50. Meanwhile, in Rome, the process against Luther continued and, eventually, Pope Leo X decided to act. To fulfill his “pastoral office,” Pope Leo X felt obliged to protect the “orthodox faith” from those who “twist and adulterate the Scriptures” so that they are “no longer the Gospel of Christ.”(14) Thus the pope issued the bull Exsurge Domine (15 June 1520), which condemned forty-one propositions drawn from various publications by Luther. Although they can all be found in Luther’s writings and are quoted correctly, they are taken out of their respective contexts. Exsurge Domine describes these propositions as “heretical or scandalous, or false, or offensive to pious ears, or dangerous to simple minds, or subversive to catholic truth,”(15) without specifying which qualification applies to which proposition. At the end of the bull, the pope expressed frustration that Luther had failed to respond to any of his overtures for discussion, although he remained hopeful that Luther would experience conversion of heart and turn away from his errors. Pope Leo gave Luther sixty days either to recant his “errors” or face excommunication.

51. Eck and Aleander, who publicized Exsurge Domine in Germany, called for Luther’s works to be burned. In response, on 10 December 1520, some Wittenberg theologians burned some books, equivalent to what would later be known as “canon law” books, along with some books of Luther’s opponents, and Luther put the papal bull into the fire. Thus, it was clear that Luther was not prepared to recant. Luther was excommunicated by the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem on 3 January 1521.

The authority of Scripture

52. The conflict concerning indulgences quickly developed into a conflict concerning authority. For Luther, the Roman curia had lost its authority by insisting only formally on its own authority instead of arguing biblically. At the beginning of the struggle, the theological authorities of Scripture, the church fathers, and the canonical tradition represented a unity for Luther. In the course of the conflict, this unity broke apart when Luther concluded that the canons as interpreted by Roman officials conflicted with Scripture. From the Catholic side, the argument was not so much about the supremacy of Scripture, with which Catholics agreed, but rather the proper interpretation of Scripture.

53. When Luther did not see a biblical basis in Rome’s statements, or thought that they even contradicted the biblical message, he began to think of the pope as the Antichrist. By this, admittedly shocking, accusation, Luther meant that the pope did not allow Christ to say what Christ wanted to say and that the pope had put himself above the Bible rather than submitting to its authority. The pope claimed that his office was instituted iure divino (“by divine right”), while Luther could not find biblical evidence for this claim.

Luther in Worms

54. According to the laws of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, a person who was excommunicated also had to be put under imperial ban. Nevertheless, the members of the Diet of Worms required that an independent authority interrogate Luther. Thus, Luther was called to Worms and the Emperor offered Luther, now a declared heretic, a safe passage to the city. Luther had expected a disputation at the Diet, but was only asked whether he had written certain books on a table in front of him, and whether he was prepared to recant.

55. Luther responded to this invitation to recant with the famous words: “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted, and my conscience is captive to the Words of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen.”(16)

56. In response, Emperor Charles V delivered a remarkable speech in which he set forth his intentions. The emperor noted that he had descended from a long line of sovereigns who had had always considered it their duty to defend the Catholic faith “for the salvation of souls” and that he had the same duty. The emperor argued that a single friar erred when his opinion was in opposition to all of Christianity for the last thousand years.(17)

57. The Diet of Worms made Luther an outlaw who had to be arrested or even killed and commanded the rulers to suppress the “Lutheran heresy” by any means. Since Luther’s argument was convincing to many of the princes and towns, they did not carry out the mandate.

Beginnings of the Reformation movement

58. Luther’s understanding of the gospel was persuasive to an increasing number of priests, monks, and preachers who tried to incorporate this understanding into their preaching. Visible signs of the changes taking place were that lay people received communion under both species, some priests and monks were marrying, certain rules of fasting were no longer observed, and disrespect was at times shown to images and relics.

59. Luther had no intention of establishing a new church, but was part of a broad and many-faceted desire for reform. He played an increasingly active role, attempting to contribute to a reform of practices and doctrines that seemed to be based on human authority alone and to be in tension with or contradiction to the Scriptures. In his treatise “To the German Nobility” (1520), Luther argued for the priesthood of all baptized and thus for an active role of the laity in church reform. Lay people played an important role in the Reformation movement, either as princes, magistrates, or ordinary people.

Need for oversight

60. Since there was no central plan and no central agency for organizing the reforms, the situation differed from town to town and village to village. A need arose to organize church visitations. As this required the authority of princes or magistrates, the reformers asked the Electoral Prince of Saxony to establish and authorize a visitation commission in 1527. Its tasks were not only to evaluate the preaching and the whole service and life of the ministers, but also to ensure that they received resources for their personal sustenance.

61. The commission installed something like a church government. The superintendents were charged with the task of overseeing the ministers of a certain region and supervising their doctrine and way of life. The commission also examined the orders of service and oversaw the unity of these orders. In 1528, a ministers’ handbook was published that addressed all their major doctrinal and practical problems. It played an important role in the history of the Lutheran doctrinal confessions.

Bringing the Scripture to the people

62. Luther, together with colleagues at the University of Wittenberg, translated the Bible into German so that more people were able to read it for themselves and, among other uses, to engage in spiritual and theological discernment for their life in the church. For that reason, Lutheran reformers established schools for both boys and girls and made serious efforts to convince parents to send their children to school.

Catechisms and hymns

63. In order to improve the poor knowledge of the Christian faith among ministers and lay people, Luther wrote his Small Catechism for a general audience and the Large Catechism for pastors and well-educated laity. The catechisms explained the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, and the creeds, and included sections on the sacraments of Holy baptism and the Holy Supper. The Small Catechism, Luther’s most influential book, greatly enhanced the knowledge of faith among ordinary people.

64. These catechisms were intended to help people live a Christian life and to gain the capacity for theological and spiritual discernment. The catechisms illustrate the fact that, for the reformers, faith meant not only trusting in Christ and his promise, but also affirming the propositional content of faith that can and must be learned.

65. To promote lay participation in the services, the reformers wrote hymns and published hymnbooks. These played an enduring role in Lutheran spirituality and became part of the treasured heritage of the whole church.

Ministers for the parishes

66. Now that the Lutheran parishes had the Scriptures in the vernacular, the catechism, hymns, a church order, and orders of service, a major problem remained, namely how to provide ministers for the parishes. During the first years of the Reformation, many priests and monks became Lutheran ministers, so that enough pastors were available. But this method of recruiting ministers eventually proved to be insufficient.

67. It is remarkable that the reformers waited until 1535 before they organized their own ordinations in Wittenberg. In the Augsburg Confession (1530), the reformers declared that they were prepared to obey the bishops if the bishops themselves would allow the preaching of the gospel according to Reformation beliefs. Since this did not happen, the reformers had to choose between maintaining the traditional way of ordaining priests by bishops, thereby giving up Reformation preaching, or keeping Reformation preaching, but ordaining pastors by other pastors. The reformers chose the second solution, reclaiming a tradition of interpreting the Pastoral Epistles that went back to Jerome in the early church.

68. Members of the Wittenberg theological faculty, acting on behalf of the church, examined both the doctrine and the lives of the candidates. Ordinations took place in Wittenberg rather than in the parishes of the ordinands, since the ministers were ordained to the ministry of the entire church. The ordination testimonies emphasized the ordinands’ doctrinal agreement with the catholic church. The ordination rite consisted in the laying on of hands and prayer to the Holy Spirit.

Theological attempts to overcome the religious conflict

69. The Augsburg Confession (1530) attempted to settle the religious conflict of the Lutheran Reformation. Its first part (articles 1–21) presents Lutheran teaching held to be in agreement with the doctrine of “the catholic church, or from the Roman church”(18) its second part deals with changes that the reformers initiated to correct certain practices understood as “misuses” (articles 22–28), giving reasons for changing these practices. The end of part 1 reads, “This is a nearly complete summary of the teaching among us. As can be seen, there is nothing here that departs from the Scriptures or the catholic church, or from the Roman church, insofar as we can tell from its writers. Because this is so, those who claim that our people are to be regarded as heretics judge too harshly.”(19)

70. The Augsburg Confession is a strong testimony to the Lutheran reformers’ resolve to maintain the unity of the church and remain within one visible church. In explicitly presenting the difference as of only minor significance, it is similar to what we today would call a differentiating consensus.

71. Immediately, some Catholic theologians saw the need to respond to the Augsburg Confession and quickly produced the Confutation of the Augsburg Confession. This Confutation closely followed the text and arguments of the Confession. The Confutation was able to affirm along with the Augsburg Confession a number of core Christian teachings such as the doctrines of the Trinity, Christ, and baptism. The Confutation, however, rejected a number of Lutheran teachings on the doctrines of the church and sacraments on the basis of biblical and patristic texts. Since Lutherans could not be persuaded by the Confutation’s arguments, an official dialogue was initiated in late August 1530 in order to reconcile the differences between the Confession and the Confutation. This dialogue, however, was unable to resolve the remaining ecclesiological and sacramental problems.

72. Another attempt to overcome the religious conflict was the so-called Religionsgespräche or Colloquies (Speyer/Hagenau [1540], Worms [1540-1], Regensburg [1541–1546]). The Emperor or his brother, King Ferdinand, convened the conversations, which took place under the leadership of an imperial representative. The goal was to persuade the Lutherans to return to the convictions of their opponents. Tactics, intrigues, and political pressure played an important role in them.

73. The negotiators achieved a remarkable text on the doctrine of justification in the Regensburger Buch (1541), but the conflict concerning the doctrine of the eucharist seemed to be insurmountable. In the end, both Rome and Luther rejected the results, leading to the ultimate failure of these negotiations.

Religious war and the Peace of Augsburg

74. The Smalcald War (1546–1547) of Emperor Charles V against the Lutheran territories aimed at defeating the princes and forcing them to revoke all changes. In the beginning the Emperor was successful. He won the war (20 July 1547). His troops were soon in Wittenberg where the Emperor hindered the soldiers from exhuming Luther’s body and burning it.

75. At the Diet in Augsburg (1547–1548), the Emperor imposed the so-called Augsburg Interim on the Lutherans, leading to endless conflicts in Lutheran territories. This document explained justification mainly as grace that stimulates love. It emphasized subordination under the bishops and the pope. However, it also permitted the marriage of priests and communion under both species.

76. In 1552, after a conspiracy of princes, a new war against the Emperor began that forced him to flee from Austria. This led to a peace treaty between Lutheran princes and King Ferdinand. Thus, the attempt to eradicate “the Lutheran heresy” through military means ultimately failed.

77. The war ended with the Peace of Augsburg in 1555. This treaty was an attempt to find ways for people of different religious convictions to live together in one country. Territories and towns that adhered to the Augsburg Confession as well as Catholic territories were recognized in the German Empire, but not people of other beliefs, such as the Reformed and the Anabaptists. The princes and magistrates had the right to determine the religion of their subjects. If the prince changed his religion, the people living in the territory would also have to change theirs, except in the areas where bishops were princes (geistliche Fürstentümer). The subjects had the right to emigrate if they did not agree with the religion of the prince.

The Council of Trent

78. The Council of Trent (1545–1563), convened a generation after Luther’s reform, began before the Smalcald War (1546–1547) and ended after the Peace of Augsburg (1555). The bull Laetare Jerusalem (19 November 1544) set three orders of business for the Council: healing of the confessional split, reforming the church, and establishing peace so that a defense against the Ottomans could be elaborated.

79. The Council decided that at each session there would be a dogmatic decree, affirming the faith of the church, and a disciplinary decree helping to reform the church. For the most part, the dogmatic decrees did not present a comprehensive theological account of the faith, but rather concentrated on those doctrines disputed by the reformers in a way that emphasized points of difference.

Scripture and tradition

80. The Council, wishing to preserve the “purity of the gospel purged of all errors,” approved its decree on the sources of revelation on 8 April 1546. Without explicitly naming it, the Council rejected the principle of sola scriptura by arguing against the isolation of Scripture from tradition. The Council decreed that the gospel, “the source of the whole truth of salvation and rule of conduct,” was preserved “in written books and unwritten traditions,” without, however, resolving the relationship between Scripture and tradition. Moreover, it taught that the apostolic traditions concerning faith and morals were “preserved in unbroken sequence in the Catholic Church.” Scripture and tradition were to be accepted “with a like feeling of piety and reverence.”(20)

81. The decree published a list of the canonical books of the Old and New Testaments.(21) The Council insisted that the sacred Scriptures can neither be interpreted contrary to the teaching of the church nor contrary to the “unanimous teaching of the Fathers” of the church. Finally, the Council declared that the old Latin vulgate edition of the Bible was an “authentic” text for use in the church.(22)

Justification

82. Regarding justification, the Council explicitly rejected both the Pelagian doctrine of works righteousness and the doctrine of justification by faith alone (sola fide), while understanding faith primarily as assent to revealed doctrine. The Council affirmed the Christological basis of justification by affirming that human beings are grafted into Christ and that the grace of Christ is necessary for the entire process of justification, although the process does not exclude dispositions for grace or the collaboration of free will. It declared the essence of justification to be not the remission of sins alone, but also the “sanctification and renovation of the inner man” by supernatural charity.(23) The formal cause of justification is “the justice of God, not that by which He Himself is just, but that by which He makes us just,” and the final cause of justification is “the glory of God and of Christ and life everlasting.”(24) Faith was affirmed as the “beginning, foundation and root” of justification.(25) The grace of justification can be lost by mortal sin and not only by the loss of faith, although it can be regained through the sacrament of penance.(26) The Council affirmed that eternal life is a grace, not merely a reward.(27)

The sacraments

83. At its seventh session, the Council presented the sacraments as the ordinary means by which “all true justice either begins, or once received gains strength, or, if lost, is restored.”(28) The Council decreed that Christ instituted seven sacraments and defined them as efficacious signs causing grace by the rite itself (ex opere operato) and not simply by reason of the recipient’s faith.

84. The debate on communion under both species expressed the doctrine that under either species the whole and undivided Christ is received.(29) After the conclusion of the Council (16 April 1565), the pope authorized the chalice for the laity under certain conditions for several ecclesiastical provinces of Germany and the hereditary territories of the Habsburgs.

85. In response to the reformers’ critique of the sacrificial character of the Mass, the Council affirmed the Mass as a propitiatory sacrifice that made present the sacrifice of the cross. The Council taught that, since in the Mass Christ the priest offers the same sacrificial gifts as on the cross, but in a different way, the Mass is not a repetition of the once-for-all sacrifice of Calvary. The Council defined that the Mass may be offered in honor of the saints and for the faithful, living and dead.(30)

86. The decree on holy orders defined the sacramental character of ordination and the existence of an ecclesiastical hierarchy based on divine ordinance. (31)

Pastoral reforms

87. The Council also initiated pastoral reforms. Its reform decrees promoted a more effective proclamation of the Word of God through the establishment of seminaries for the better training of priests and through the requirement of preaching on Sundays and holy days. Bishops and pastors were obliged to reside in their dioceses and parishes. The Council eliminated some abuses in matters of jurisdiction, ordination, patronage, benefices, and indulgences at the same time that it expanded episcopal powers. Bishops were empowered to make visitations of exempt parochial benefices and oversee the pastoral work of exempt orders and chapters. It provided for provincial and diocesan synods. In order better to communicate the faith, the Council encouraged the emerging practice of writing catechisms, such as those of Peter of Canisius, and made provision for the Roman Catechism.

Consequences

88. The Council of Trent, although to a large extent a response to the Protestant Reformation, did not condemn individuals or communities but specific doctrinal positions. Because the doctrinal decrees of the Council were largely in response to what it perceived to be Protestant errors, it shaped a polemical environment between Protestants and Catholics that tended to define Catholicism over and against Protestantism. In this approach, it mirrored many of the Lutheran confessional writings, which also defined Lutheran positions by opposition. The decisions of the Council of Trent laid the basis for the formation of Catholic identity up to the Second Vatican Council.

89. By the end of the third gathering of the Council of Trent, it had to be soberly acknowledged that the unity of the church in the Western world had been shattered. New church structures developed in the Lutheran territories. The Peace of Augsburg of 1555 at first secured stable political relationships, but it could not prevent the great European conflict of the seventeenth century, the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). The establishment of secular nation-states with strong confessionalistic delineations remained a burden inherited from the Reformation period.

The Second Vatican Council

90. While the Council of Trent largely defined Catholic relations with Lutherans for several centuries, its legacy must now be viewed through the lens of the actions of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). This Council made it possible for the Catholic Church to enter the ecumenical movement and leave behind the charged polemic atmosphere of the post-Reformation era. The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church (Lumen Gentium), the Decree on Ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratio), the Declaration on Religious Freedom (Dignitatis Humanae), and the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation (Dei Verbum) are foundational documents for Catholic ecumenism. Vatican II, while affirming that the Church of Christ subsists in the Catholic Church, also acknowledged, “many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside of its visible structure. These elements, as gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, are forces impelling toward catholic unity” (LG 8). There was a positive appreciation of what Catholics share with other Christian churches such as the creeds, baptism, and the Scriptures. A theology of ecclesial communion affirmed that Catholics are in a real, if imperfect, communion with all who confess Jesus Christ and are baptized (UR 2).

Chapter IV

Basic Themes of Martin Luther’s Theology

in Light of the Lutheran–Roman Catholic Dialogues

91. Since the sixteenth century, basic convictions of both Martin Luther and Lutheran theology have been a matter of controversy between Catholics and Lutherans. Ecumenical dialogues and academic research have analyzed these controversies and attempted to overcome them by identifying the different terminologies, different thought structures, and different concerns that do not necessarily exclude each other.

92. In this chapter, Catholics and Lutherans jointly present some of the main theological affirmations developed by Martin Luther. This common description does not mean that Catholics agree with everything that Martin Luther said as presented here. An ongoing need for ecumenical dialogue and mutual understanding remains. Nevertheless, we have reached a stage in our ecumenical journey that enables us to give this common account.

93. It is important to distinguish between Luther’s theology and Lutheran theology and, above all, between Luther’s theology and the doctrine of the Lutheran churches as expressed in their confessional writings. This doctrine is the primary reference point for the ecumenical dialogues. Still, it appropriate here to concentrate on Luther’s theology because of the anniversary commemoration of 31 October 1517.

Structure of this chapter

94. This chapter focuses on only four topics within Luther’s theology: justification, eucharist, ministry, and Scripture and tradition. Because of their importance in the life of the church, and on account of the controversies they occasioned for centuries, they have been extensively treated in the Catholic–Lutheran dialogues. The following presentation harvests the results of these dialogues.

95. The discussion of each topic proceeds in three steps. Luther’s perspective on each of the four theological themes is presented first, followed by a short description of Catholic concerns regarding that topic. A summary then shows how Luther’s theology has been brought into conversation with Catholic doctrine in ecumenical dialogue. This section highlights what has been jointly affirmed and identifies remaining differences.

96. An important topic for further discussion is how we can deepen our convergence on those issues where we still have different emphases, especially with respect to the doctrine of the church.

97. It is important to note that not all dialogue statements between Lutherans and Catholics carry the same weight of consensus, nor have they all been equally received by Catholics and Lutherans. The highest level of authority lies with the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, signed by representatives of the Lutheran World Federation and the Roman Catholic Church in Augsburg, Germany, on 31 October 1999 and affirmed by the World Methodist Council in 2006. The sponsoring bodies have received other international and national dialogue commission reports, but these reports vary in their impact on the theology and life of Lutheran and Catholic communities. Church leaders now share the ongoing responsibility for appreciating and receiving the accomplishments of ecumenical dialogues.

Martin Luther’s medieval heritage

98. Martin Luther was deeply embedded in the late Middle Ages. He could be all at once receptive to, critically distant from, or in the process of moving beyond its theologies. In 1505, he became a brother of the order of Augustinian hermits in Erfurt and, in 1512, a professor of sacred theology in Wittenberg. In this position, he focused his theological work primarily on the interpretation of biblical Scriptures. This emphasis on Holy Scripture was fully in line with what the rules of the order of the Augustinian Hermits expected a friar to do, namely to study and meditate on the Bible not only for his own personal benefit, but also for the spiritual benefit of others. The church fathers, especially Augustine, played a vital role in the development and final shape of Luther’s theology. “Our theology and St. Augustine are making progress,”(32) he wrote in 1517, and in the “Heidelberg Disputation” (1518) he refers to St Augustine as “the most faithful interpreter”(33) of the apostle Paul. Thus, Luther was very deeply rooted in the patristic tradition.

Monastic and mystical theology

99. While Luther had a predominantly critical attitude toward scholastic theologians, as an Augustinian hermit for twenty years, he lived, thought, and did theology in the tradition of monastic theology. One of the most influential monastic theologians was Bernard of Clairvaux, whom Luther highly appreciated. Luther’s way of interpreting Scripture as the place of encounter between God and human beings shows clear parallels with Bernard’s interpretation of Scripture.

100. Luther was also deeply rooted in the mystical tradition of the late medieval period. He found help in, and felt understood by, the German sermons of John Tauler (d. 1361). In addition, Luther himself published the mystical text, Theologia deutsch (“German Theology,” 1518), which had been written by an unknown author. This text became widespread and well known through Luther’s publication of it.

101. Throughout his whole life, Luther was very grateful to the superior of his order, John of Staupitz, and his Christ-centered theology, which consoled Luther in his afflictions. Staupitz was a representative of nuptial mysticism. Luther repeatedly acknowledged his helpful influence, saying, “Staupitz started this doctrine”(34)and praising him for “first of all being my father in this doctrine, and having given birth [to me] in Christ.”(35) In the late Middle Ages, a theology was developed for the laity. This theology (Frömmigskeitstheologie) reflected upon the Christian life in practical terms and was oriented to the practice of piety. Luther was stimulated by this theology to write treatises of his own for the laity. He took up many of the same topics but gave them his own distinct treatment.

Justification

Luther’s understanding of justification

102. Luther gained one of his basic Reformation insights from reflecting on the sacrament of penance, especially in relation to Matthew 16:18. In his late medieval education, he was trained to understand that God would forgive a person who was contrite for his or her sin by performing an act of loving God above all things, to which God would respond according to God’s covenant (pactum) by granting anew God’s grace and forgiveness (facienti quod in se est deus non denegat gratiam),(36) so that the priest could only declare that God had already forgiven the penitent’s sin. Luther concluded that Matthew 16 said just the opposite, namely that the priest declared the penitent righteous, and by this act on behalf of God, the sinner actually became righteous.

Word of God as promise

103. Luther understood the words of God as words that create what they say and as having the character of promise (promissio). Such a word of promise is said in a particular place and time, by a particular person, and is directed to a particular person. A divine promise is directed toward a person’s faith. Faith in turn grasps what is promised as promised to the believer personally. Luther insisted that such faith is the only appropriate response to a word of divine promise. A human being is called to look away from him or herself and to look only at the word of God’s promise and trust fully in it. Since faith grounds us in Christ’s promise, it grants the believer full assurance of salvation. Not to trust in this word would make God a liar or one on whose word one could not ultimately rely. Thus, in Luther’s view, unbelief is the greatest sin against God.

104. In addition to structuring the dynamic between God and the penitent within the sacrament of penance, the relationship of promise and trust also shapes the relationship between God and human beings in the proclamation of the Word. God wishes to deal with human beings by giving them words of promise—sacraments are also such words of promise—that show God’s saving will towards them. Human beings, on the other hand, should deal with God only by trusting in his promises. Faith is totally dependent on God’s promises; it cannot create the object in which human beings put their trust.

105. Nevertheless, trusting God’s promise is not a matter of human decision; rather, the Holy Spirit reveals this promise as trustworthy and thus creates faith in a person. Divine promise and human belief in that promise belong together. Both aspects need to be stressed, the “objectivity” of the promise and the “subjectivity” of faith. According to Luther, God not only reveals divine realities as information with which the intellect must agree; God’s revelation also always has a soteriological purpose directed towards the faith and salvation of believers who receive the promises that God gives “for you” as words of God “for me” or “for us” (pro me, pro nobis).

106. God’s own initiative establishes a saving relation to the human being; thus salvation happens by grace. The gift of grace can only be received, and since this gift is mediated by a divine promise, it cannot be received except by faith, and not by works. Salvation takes place by grace alone. Nevertheless, Luther constantly emphasized that the justified person would do good works in the Spirit.

By Christ alone

107. God’s love for human beings is centered, rooted, and embodied in Jesus Christ. Thus, “by grace alone” is always to be explained by “by Christ alone.” Luther describes the relationship of human persons with Christ by using the image of a spiritual marriage. The soul is the bride; Christ is the bridegroom; faith is the wedding ring. According to the laws of marriage, the properties of the bridegroom (righteousness) become the properties of the bride, and the properties of the bride (sin) become the properties of the bridegroom. This “joyful exchange” is the forgiveness of sins and salvation.

108. The image shows that something external, namely Christ’s righteousness, becomes something internal. It becomes the property of the soul, but only in union with Christ through trust in his promises, not in separation from him. Luther insists that our righteousness is totally external because it is Christ’s righteousness, but it has to become totally internal by faith in Christ. Only if both sides are equally emphasized is the reality of salvation properly understood. Luther states, “It is precisely in faith that Christ is present.”(37) Christ is “for us” (pro nobis) and in us (in nobis), and we are in Christ (in Christo).

Significance of the law

109. Luther also perceived human reality, with respect to the law in its theological or spiritual meaning, from the perspective of what God requires from us. Jesus expresses God’s will by saying, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” (Mt 22:37). That means that God’s commandments are fulfilled only by total dedication to God. This includes not only the will and the corresponding outward actions, but also all aspects of the human soul and heart such as emotions, longing, and human striving, that is, those aspects and movements of the soul either not under the control of the will or only indirectly and partially under the control of the will through the virtues.

110. In the legal and moral spheres, there exists an old rule, intuitively evident, that nobody can be obliged to do more than he or she is able to do (ultra posse nemo obligatur). Thus, in the Middle Ages, many theologians were convinced that this commandment to love God must be limited to the will. According to this understanding, the commandment to love God does not require that all motions of the soul should be directed and dedicated to God. Rather, it would be enough that the will loves (i.e., wills) God above all (diligere deum super omnia).

111. Luther argued, however, that there is a difference between a legal and a moral understanding of the law, on the one hand, and a theological understanding of it, on the other. God has not adapted God’s commandments to the conditions of the fallen human being. Instead, theologically understood, the commandment to love God shows the situation and the misery of human beings. As Luther wrote in the “Disputation against Scholastic Theology,” “Spiritually that person [only] does not kill, does not do evil, does not become enraged when he neither becomes angry nor lusts.”(38) In this respect, divine law is not primarily fulfilled by external actions or acts or the will but by the wholehearted dedication of the whole person to the will of God.

Participation in Christ’s righteousness

112. Luther’s position, that God requires wholehearted dedication in fulfilling God’s law, explains why Luther emphasized so strongly that we totally depend on Christ’s righteousness. Christ is the only person who totally fulfilled God’s will, and all other human beings can only become righteous in a strict, i.e., theological sense, if we participate in Christ’s righteousness. Thus, our righteousness is external insofar as it is Christ’s righteousness, but it must become our righteousness, that is, internal, by faith in Christ’s promise. Only by participation in Christ’s wholehearted dedication to God can we become wholly righteous.

113. Since the gospel promises us, “Here is Christ and his Spirit,” participation in Christ’s righteousness is never realized without being under the power of the Holy Spirit who renews us. Thus, becoming righteous and being renewed are intimately and inseparably connected. Luther did not criticize fellow theologians such as Gabriel Biel for too strong an emphasis on the transforming power of grace; on the contrary, he objected that they did not emphasize it strongly enough as being fundamental to any real change in the believer.

Law and gospel

114. According to Luther, this renewal will never come to fulfillment as long as we live. Therefore, another model of explaining human salvation, taken from the Apostle Paul, became important for Luther. In Romans 4:3, Paul refers to Abraham in Genesis 15:6 (“Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness”) and concludes, “To one who without works trusts him who justifies the ungodly, such faith is reckoned as righteousness” (Rom 4:5).

115. This text from Romans incorporates the forensic imagery of someone in a courtroom being declared righteous. If God declares someone righteous, this changes his or her situation and creates a new reality. God’s judgment does not remain “outside” the human being. Luther often uses this Pauline model in order to emphasize that the whole person is accepted by God and saved, even though the process of the inner renewal of the justified into a person wholly dedicated to God will not come to an end in this earthly life.

116. As believers who are in the process of being renewed by the Holy Spirit, we still do not completely fulfill the divine commandment to love God wholeheartedly and do not meet God’s demand. Thus the law will accuse us and identify us as sinners. With respect to the law, theologically understood, we believe that we are still sinners. But, with respect to the gospel that promises us “Here is Christ’s righteousness,” we are righteous and justified since we believe in the gospel’s promise. This is Luther’s understanding of the Christian believer who is at the same time justified and yet a sinner (simul iustus et peccator).

117. This is no contradiction since we must distinguish two relations of the believer to the Word of God: the relation to the Word of God as the law of God insofar as it judges the sinner, and the relation to the Word of God as the gospel of God insofar as Christ redeems. With respect to the first relation we are sinners; with respect to the second relation we are righteous and justified. This latter is the predominant relationship. That means that Christ involves us in a process of continuous renewal as we trust in his promise that we are eternally saved.

118. This is why Luther emphasized the freedom of a Christian so strongly: the freedom of being accepted by God by grace alone and by faith alone in Christ’s promises, the freedom from the accusation of the law by the forgiveness of sins, and the freedom to serve one’s neighbor spontaneously without seeking merits in doing so. The justified person is, of course, obligated to fulfill God’s commandments, and will do so under the motivation of the Holy Spirit. As Luther declared in the Small Catechism: “We are to fear and love God, so that we…,” after which follow his explanations of the Ten Commandments.(39)

Catholic concerns regarding justification

119. Even in the sixteenth century, there was a significant convergence between Lutheran and Catholic positions concerning the need for God’s mercy and humans’ inability to attain salvation by their own efforts. The Council of Trent clearly taught that the sinner cannot be justified either by the law or by human effort, anathematizing anyone who said that “man can be justified before God by his own works which are done either by his own natural powers, or through the teaching of the Law, and without divine grace through Christ Jesus.”(40)

120. Catholics, however, had found some of Luther’s positions troubling. Some of Luther’s language caused Catholics to worry whether he denied personal responsibility for one’s actions. This explains why the Council of Trent emphasized the human person’s responsibility and capacity to cooperate with God’s grace. Catholics stressed that the justified should be involved in the unfolding of grace in their lives. Thus, for the justified, human efforts contribute to a more intense growth in grace and communion with God.

121. Furthermore, according to the Catholic reading, Luther’s doctrine of “forensic imputation” seemed to deny the creative power of God’s grace to overcome sin and transform the justified. Catholics wished to emphasize not only the forgiveness of sins but also the sanctification of the sinner. Thus, in sanctification the Christian receives that “justice of God” whereby God makes us just.

Lutheran–Catholic dialogue on justification

122. Luther and the other reformers understood the doctrine of the justification of sinners as the “first and chief article,”(41) the “guide and judge over all parts of Christian doctrine.”(42) That is why a division on this point was so grave and the work to overcome this division became a matter of highest priority for Catholic–Lutheran relations. In the second half of the twentieth century, this controversy was the subject of extensive investigations by individual theologians and a number of national and international dialogues.

123. The results of these investigations and dialogues are summarized in the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification and were, in 1999, officially received by the Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation. The following account is based on this Declaration, which offers a differentiating consensus comprised of common statements along with different emphases of each side, with the claim that these differences do not invalidate the commonalities. It is thus a consensus that does not eliminate differences, but rather explicitly includes them.

By grace alone

124. Together Catholics and Lutherans confess: “By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works” (JDDJ 15). The phrase “by grace alone” is further explained in this way: “the message of justification ... tells us that as sinners our new life is solely due to the forgiving and renewing mercy that God imparts as a gift and we receive in faith, and never can merit in any way” (JDDJ 17).(43)

125. It is within this framework that the limits and the dignity of human freedom can be identified. The phrase “by grace alone,” in regard to a human being’s movement toward salvation, is interpreted in this way: “We confess together that all persons depend completely on the saving grace of God for their salvation. The freedom they possess in relation to persons and the things of this world is no freedom in relation to salvation” (JDDJ 19).

126. When Lutherans insist that a person can only receive justification, they mean, however, thereby “to exclude any possibility of contributing to one’s own justification, but do not deny that believers are fully involved personally in their faith, which is effected by God’s Word” (JDDJ 21).

127. When Catholics speak of preparation for grace in terms of “cooperation,” they mean thereby a “personal consent” of the human being that is “itself an effect of grace, not an action arising from innate human abilities” (JDDJ 20). Thus, they do not invalidate the common expression that sinners are “incapable of turning by themselves to God to seek deliverance, of meriting their justification before God, or of attaining salvation by their own abilities. Justification takes place solely by God’s grace” (JDDJ 19).